Archive for the ‘Television’ Category

Filming with David Walliams for Who Do You Think You Are? and a look into his great-grandfather’s wartime service

Back in early March just before lockdown I spent a half day filming with David Walliams at the Guards’ Chapel for the new series of Who Do You Think You Are? David’s episode was broadcast tonight, 19 October, on BBC One. I was asked to set the scene for David’s great grandfather, John Boorman, who served in the Grenadier Guards.

With David Walliams at the Guard’s Chapel filming Who Do You Think You Are?

His was a fascinating but ultimately tragic story. Having enlisted at the end of September 1914 it is possible that his above average build (he weighed 140 pounds and had an expanded chest of 36 inches) alongside his height of 5 feet 9 inches meant he was guided in the direction of the Guards by recruiters.

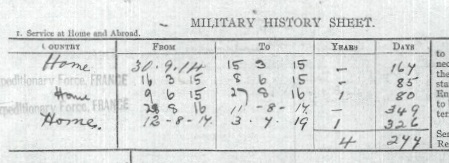

Having undergone training John proceeded overseas. His Medal Index Card and surviving service record confirm his date of arrival in France as 16 March 1915. John joined the 1st Battalion and while the service record does not say when he joined them, the battalion’s war diary notes the arrival of a draft of six officers and 350 men on 20 March 1915. It is assumed John was in this draft.

Extract from John Boorman’s service record showing time spent in the UK and overseas

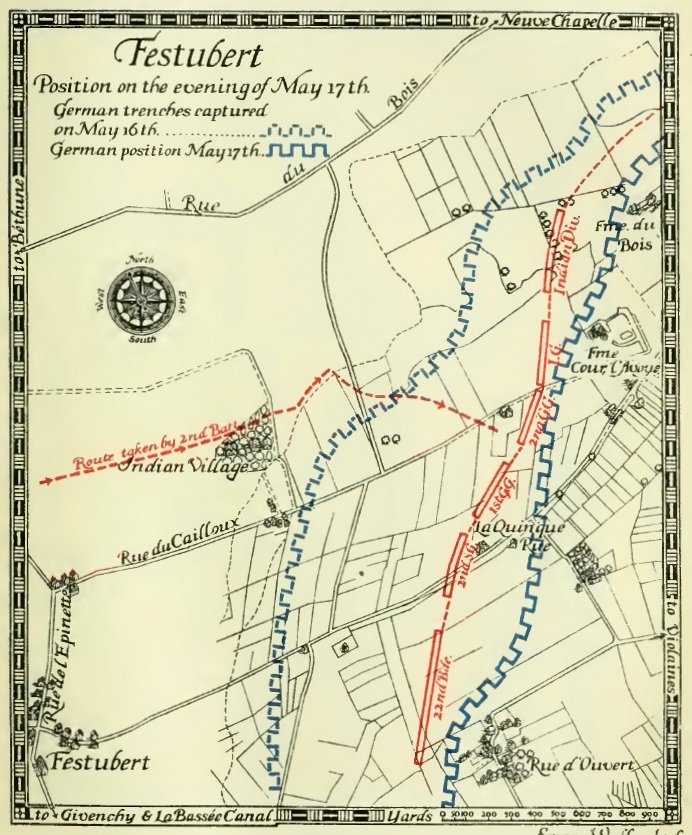

Two months of trench routine and a few weeks break in divisional reserve during which the battalion practice drill and route marching precede John’s first battle, the Battle of Festubert. In comparison to the titanic battles of 1916 & 1917 this affair, in the flat lands of French Flanders, was small but no less bloody. To soften up German positions over 100,000 shells had been fired before the assault. Early in the morning of 16 May the 1st Grenadier Guards followed behind the 2nd Border Regiment, passing through them to attack German trenches. There was no great distance gained and it certainly didn’t alter the course of the war but this action was John’s first taste of the harsh brutality of war. Battalion reports describe close quarter fighting, killing the enemy, taking prisoners plus clearing trenches by throwing bombs. It was a tough baptism of fire, as recorded in Ponsonby’s Volume 1 of The Grenadier Guards in the Great War of 1914-1918:

The 1st Battalion Grenadiers came in for a great deal of shelling, and one shell burst in the middle of No. 8 Platoon, killing four men and wounding many others, including Lieutenant Dickinson and Lieutenant St. Aubyn, who was struck in the face by a piece of shrapnel. All the time a stream of wounded from the front trenches was passing by, some walking and some on stretchers.

Another entry in the Guards’ history records:

Rain began to fall at 6 p.m., and grew into a steady downpour. In the newly won trenches the men were soaked to the skin, and spent a miserable night. Everywhere the wounded, both British and Germans, lay about groaning.

For someone with only two months service in France those images must have made an impression. During the action at Festubert the 1st Battalion lost 2 officers killed, 2 officers wounded and 113 Other Ranks killed, wounded and missing.

Guards at the Battle of Festubert, May 1915

John was invalided back home for fifteen months, suffering from shell shock and returned to France on 28 August 1916. What is unclear is exactly when he rejoined the battalion as September 1916 sees many drafts arrive – 90 Other Ranks on 15th, 60 on 17th, 35 on 19th, 20 on 22nd, 23 on 27th and 72 on the 30th.

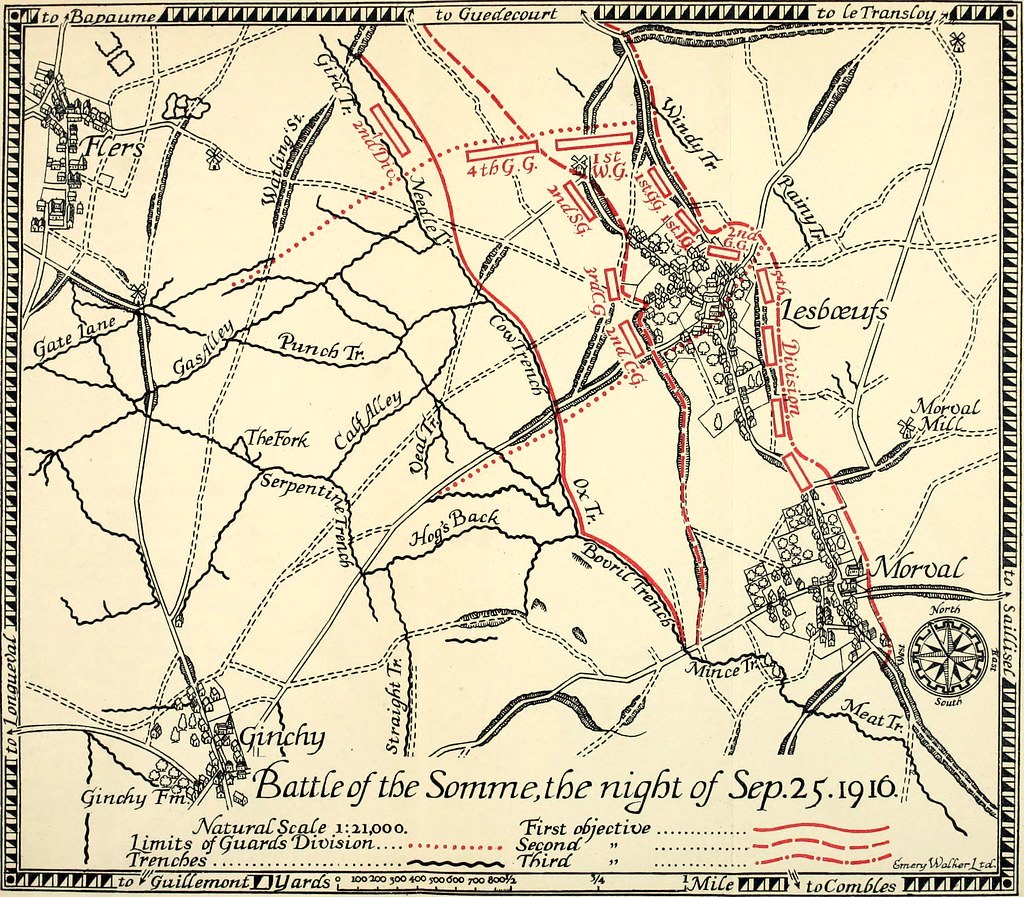

Those fresh men were much needed as the battalion was heavily involved in the Battle of the Somme that month. The attack towards the village of Lesboeufs was a costly affair for the Grenadier Guards, now part of the Guards Division. They had been in action on the 15/16th September but it was on the 25th that they took a major part. A few days prior to this the battalion was employed digging assembly trenches from which they would attack. The assault of the 25th was a success with the 1st Battalion passing through other Guards units to take their objective. The war diary has the wonderful line ‘Huns thoroughly demoralised’. Demoralised they may have been, but John’s battalion had paid the price for their success. In 11 days of action from 15-26 September they sustained a staggering 611 casualties.

Guards Division on 25 Sept 1916 at the Battle of the Somme

The month of October was spent way out of the line, absorbing new reinforcements and training before moving back to ground west of Lesboeufs in mid-November. By this time the Battle of the Somme was coming to an end. At least the men would no longer have to leave their trenches to assault enemy positions. But that did not mean an end to casualties – enemy shellfire saw to that. Holding exposed shellhole positions joined up to make short sections of trenches, John’s battalion endured mud and tough conditions that the battle had created. Even getting to frontline positions meant miles of trudging along muddy paths and duckboard tracks. Safety, warmth and aid would have seemed a long way away.

Having contended with autumnal mud it was a horribly cold winter with temperatures falling to minus 20 Celsius for a six week period. One blessing of this plummet in temperatures was the mud froze, but so did water…and men. The main enemy at this point was the weather, not the Germans. In mid-March John was admitted to No.34 CCS for treatment of lumbago and “ICT feet”. Having endured such terrible trench conditions many men suffered problems with their feet. It is likely that John moved to a hospital in Rouen, thereby missing his battalion’s part in pursuing the Germans in their retreat to the Hindenburg Line. At some point he rejoined his battalion and moved northward to the Belgian city of Ypres. This was for the start of the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) during which the Guards Division attacked on the opening day, 31 July 1917.

And for the filming with David, this was as far as I got! I was asked to set the scene for John’s war up to this point. David went over to Ypres and was shown where his great grandfather was wounded. The records show John Boorman arrived back in the UK on 11 August 1917 having been wounded in the left leg below the knee. Despite escaping the horrors of the battlefield John’s war continued. In April 1918 he was admitted to hospital and found to be suffering from mental instability (delusional insanity). A few months after he was transferred to the County of Middlesex War Hospital which contained a specialist military mental hospital. Sadly, it appears John never recovered from the mental scars of service on the Western Front and died, still in care, in 1962. His is a tragic story that reminds us of the enduring effect that war had on many men. While some seemed to return to civvie life and get on with things, return to work, raise a family and function normally, other men were unable to do so and suffered mental anguish for the rest of their lives.

My thanks to the estimable Chris Baker of https://www.fourteeneighteen.co.uk/ who did so much of the research into John Boorman’s story and provided me with a copy of the report he had prepared for Wall to Wall.

JB

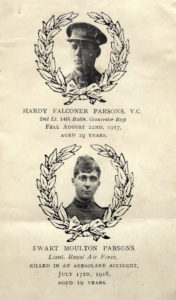

Second Lieutenant Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. Image courtesy Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Ref GLRRM:04750.6

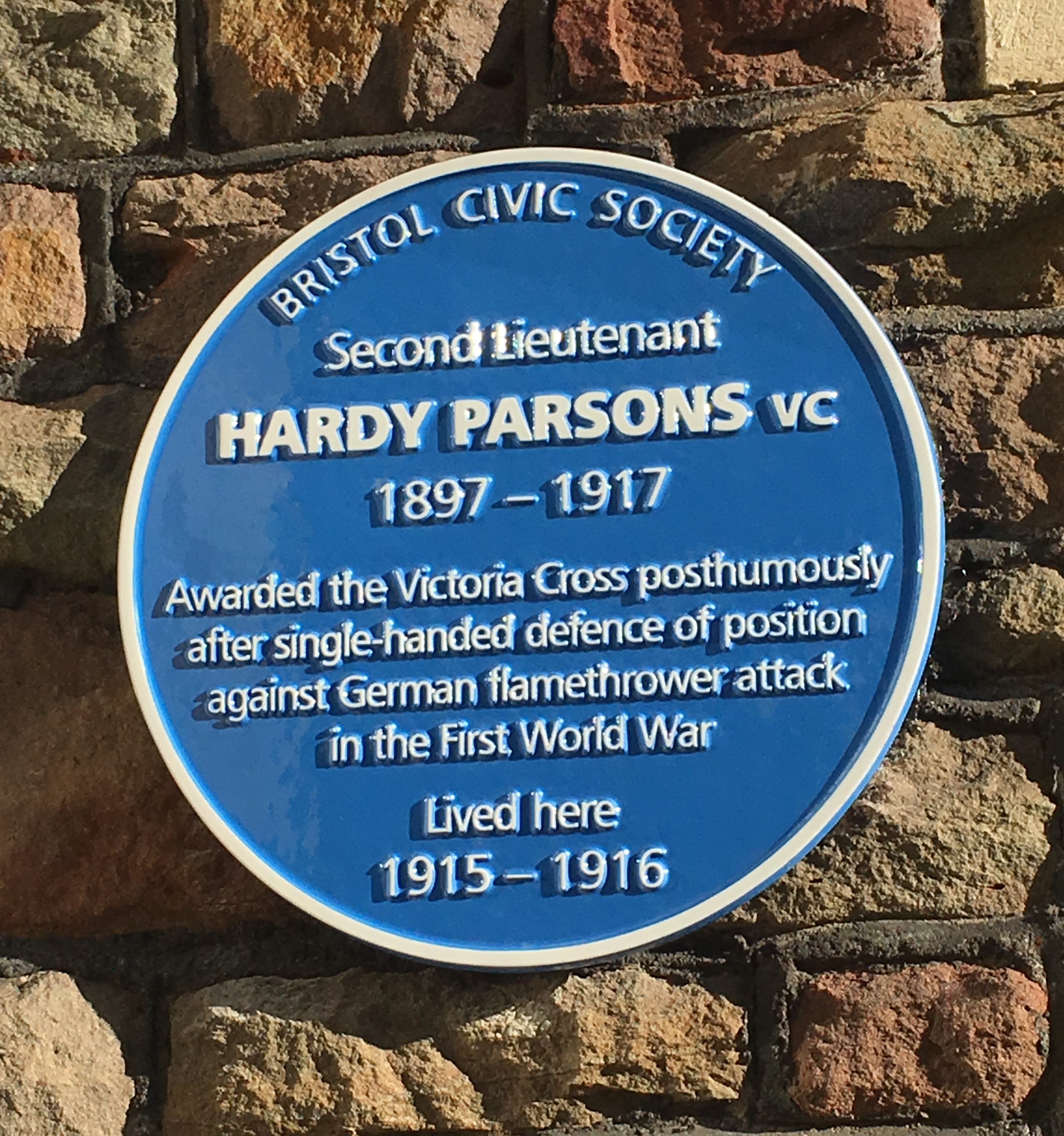

Today saw the unveiling of a Bristol Civic Society blue plaque at the former Bristol home of my local Victoria Cross recipient, 2/Lt Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. He lived a fifteen minute walk from my house and I have known his story for the past fourteen years that I have lived in the city.

My colleague Clive Burlton and I were determined to see Hardy’s strong association with Bristol and the West Country recognised. As his Government funded VC commemorative stone was unveiled in Rishton, Lancashire back in August we have spent the last year working on honouring Hardy’s local connections with a Bristol Civic Society blue plaque.

The plaque was unveiled by the Archie Smith and Grace Tyrrell, Head Boy and Head Girl of Kingswood School along with the Lord Mayor of Bristol, Cllr Lesley Alexander. The ceremony was attended by members of the Bristol Civic Society; the former Gloucestershire Regiment; the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum; the Bristol University Officer Training Corps; Kingswood School, Bath, Redland Green School and Dolphin Schools in Bristol; bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles Regiment; members of the Western Front Association and the Bristol Great War network and representatives of the Kingswood Association, whose generous donation enabled the plaque to be made and installed. Also attending were the Deputy Lord-Lieutenant for the County and City of Bristol, Colonel Andrew Flint and the Dean of Bristol, the Very Rev Dr David Hoyle. In total, around 100 people were in attendance for the ceremony. Afterwards a sizeable number of us were invited back to the Artillery Grounds on Whiteladies Road for light refreshments as guests of Bristol University Officer Training Corps.

Images of the unveiling ceremony can found below, followed by the culmination of much detailed research into Hardy’s life by Clive Burlton and myself. I can only hope that the people of Bristol and Bath embrace his memory. He deserves that.

Blue plaque for Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at 54, Salisbury Road, Redland, Bristol

Clive Burlton gives the opening address

Jeremy Banning providing the historical background to the life of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

The Lord Mayor of Bristol with members of Bristol University Officer Training Corps and bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles

A delighted Jeremy Banning and Clive Burlton with Hardy’s new blue plaque

The ceremony was well attended by the military

After the ceremony many of those attended were able to mingle and discuss Hardy’s life

Bristol 24/7 have also covered the story: https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/pictures-blue-plaque-revealed-wwi-soldier-redland/ as have BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-41918314. Our BBC Points West interview is available for a week from 16 minutes in here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b09bzw5f/points-west-evening-news-08112017

The life of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

Hardy Falconer Parsons was born on 30 June 1897 at Rishton, near Blackburn, Lancashire, the first of three boys. His father, the Rev James Ash Parsons, was a Wesleyan Minister whilst his mother Henrietta (known as Rita) was the daughter of a railway inspector from York. Hardy’s rather unusual middle name came from Rita – Falconer was her maiden name.

The Rev James Ash Parsons had spent eleven years in total in the slums of East London as superintendent of the Methodist Leysian Mission. Ill health forced him and Rita to St Anne’s on Sea, south of Blackpool and it was whilst living here that Hardy was born. There followed three years at Arnside immediately south of the Lake District. Clearly, the ethos of duty and service to others, so well practiced by his parents, was a huge part of Hardy’s upbringing.

Hardy’s first school was King Edward VII School at Lytham St Annes. From the paper work we have found it appears the family moved to Bristol in 1912 when the Rev James Ash Parsons became pastor at the Old King Street Wesleyan Chapel (sadly, now demolished). The family moved to 54 Salisbury Road in Redland and Hardy attended Kingswood School in Bath until April 1915.

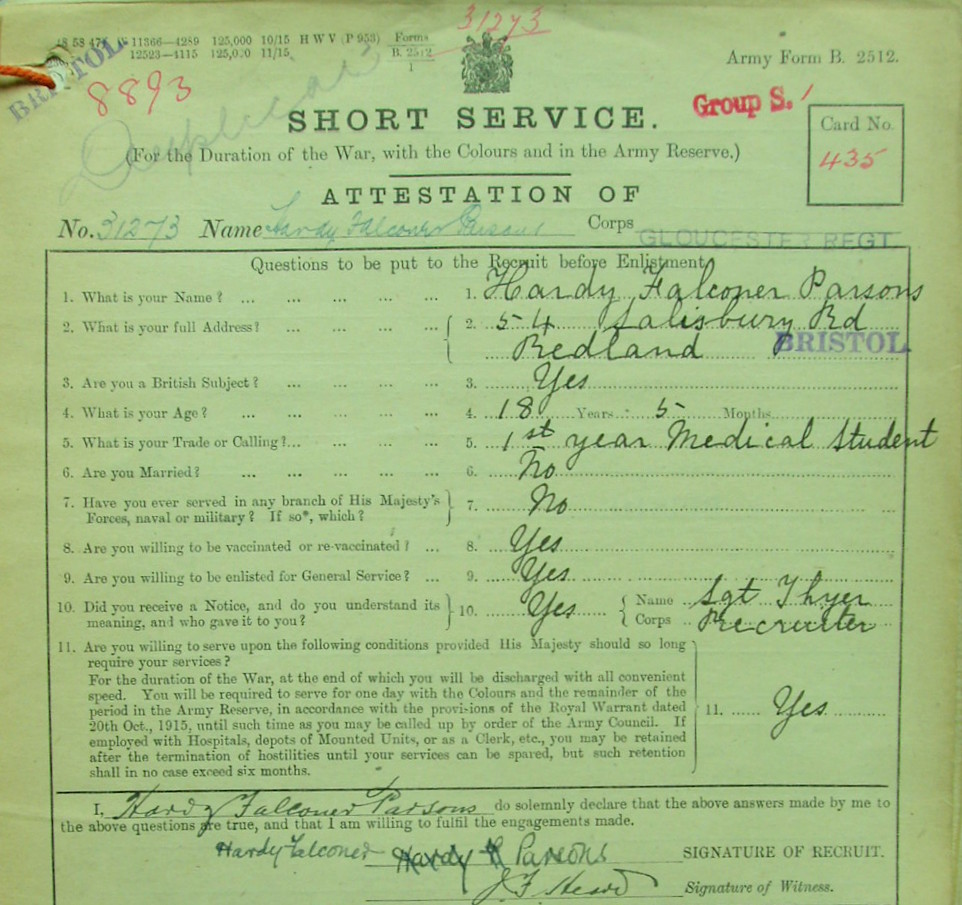

Extract from attestation papers of Hardy Falconer Parsons (National Archives: WO339/73298)

After school Hardy Parsons became a Medical Student at Bristol University with the aim of becoming a medical missionary. At the end of November 1915, during his first year at the University he signalled his wish to volunteer for service by attesting when aged just 18 years & 5 months but was immediately placed on the Army Reserve.

He had previously declined a safe post in a Government munitions laboratory, feeling that he ought not to withhold himself from the fullest sacrifice. He hated war, but recognised that the making of munitions was just as much war work as was the actual taking of life.

He joined the University’s Officer Training Corps in May 1916, a month shy of his 19th birthday, and then passed his first Bachelor of Medicine degree. His attestation papers make interesting reading – recording that he was a tall man, especially for that time, standing at 6ft ¾ inch tall. In early October 1916 he was posted to 6th Officer Cadet Battalion at Balliol College, Oxford and, on 25 January 1917, was appointed to the Gloucestershire Regiment as a Second Lieutenant.

He eventually joined the 14th Battalion in March, a unit which had previously been a ‘Bantam’ battalion – with men of 5ft 3 inches and less serving in its ranks. By the time the nearly 6ft 1 inch Hardy joined the battalion this unique distinction had been very much diluted. In February 1917 the battalion war diary records 475 ‘normal size men’ joining the battalion.

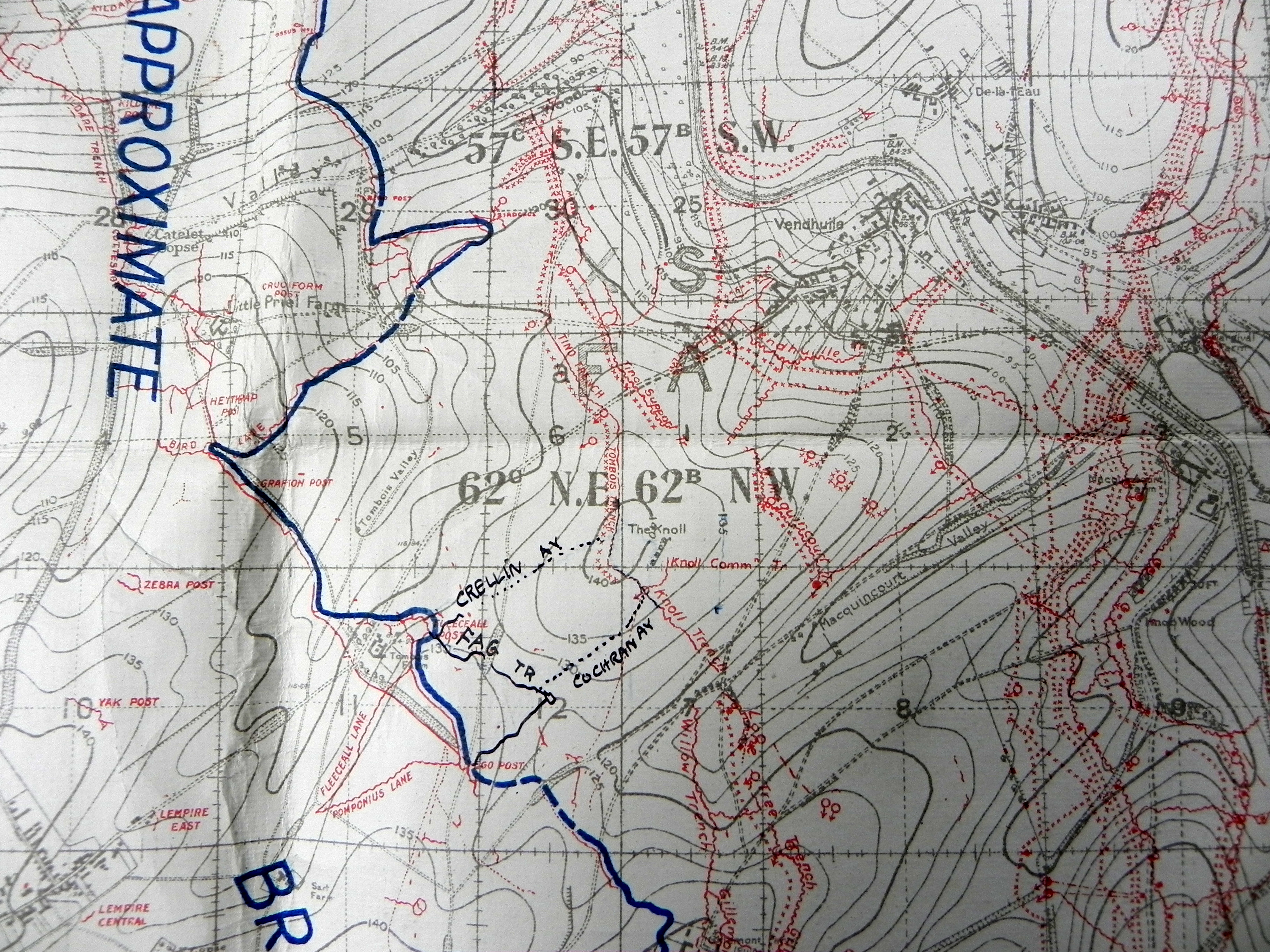

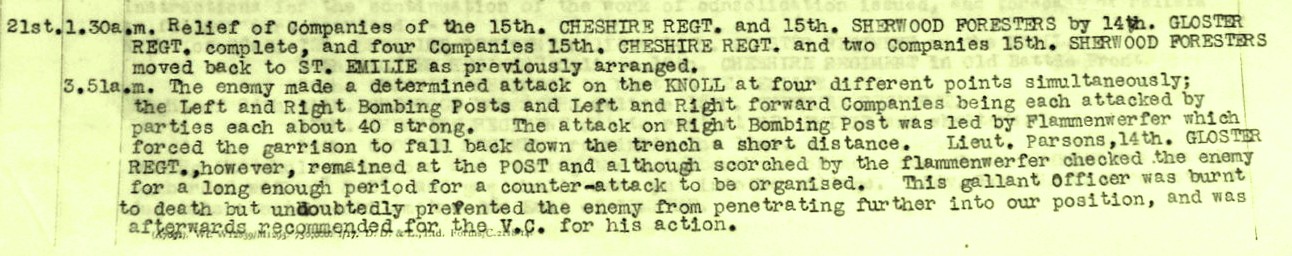

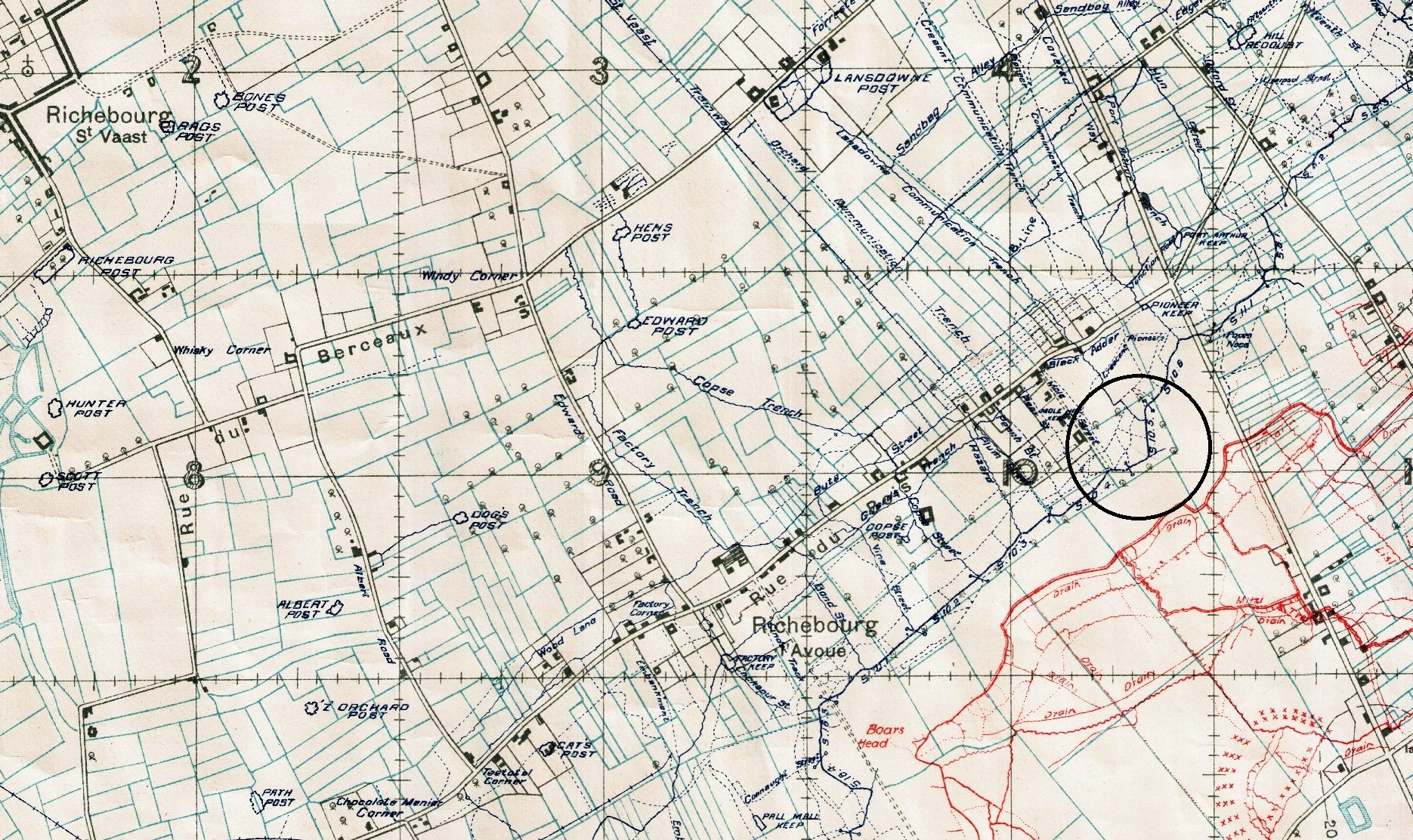

Trench map extract of The Knoll – captured by 105 Infantry Brigade on 19 August 1917

On 21 August 1917 near the village of Vendhuile in the eastern part of the Somme, Hardy’s battalion were holding recently captured trenches at a position known as The Knoll in the Hindenburg Line outpost zone. Their relief of the units who had captured the Knoll some two days before was completed by 1.30am that night.

Modern view of The Knoll, photographed October 2017. Vendhuile, the Hindenburg Line and St Quentin Canal are out of view in the valley.

It was a critical position which afforded observation over the Hindenburg Line and St Quentin canal a mile away – observation the British wanted and the Germans wanted to prevent. In fact, men from Bristol’s 1/4th and 1/6th Territorial battalions had fought for the same view in this same position four months previously.

The loss of such critical terrain forced the Germans into a devastating counter-attack. As recorded in the Brigade war diary, at 3.51am the Germans struck. Militarily, it was a brilliantly executed counter-attack by the Germans – The Knoll being attacked at four points simultaneously. German infantry were accompanied by special detachments using portable flamethrowers. These forced Hardy Parsons’ men back. However, he alone stuck to his bombing post and held his position, throwing bombs (hand grenades) at approaching Germans until a British counter-attack could be launched. The counter-attack was successful – the Germans were repulsed from the trenches around The Knoll and within 40 minutes this bloody action was over. Much of this success is due to Hardy’s refusal to yield ground.

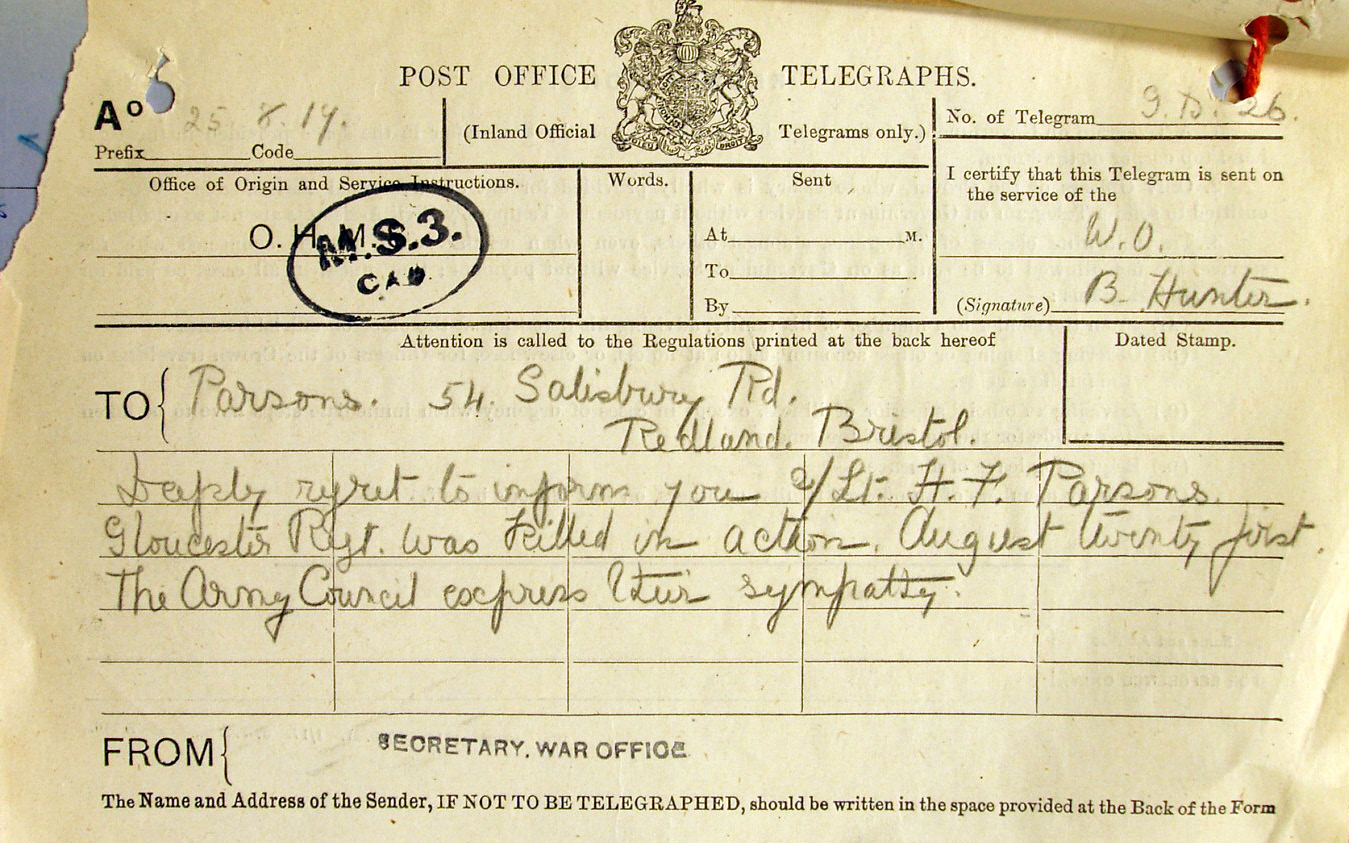

Telegram sent to the Rev James Ash Parsons informing him of Hardy’s death

During his heroic sole defence of The Knoll Hardy had been severely burnt by liquid fire. Writing these words over a hundred years later I cannot begin to imagine the sense of duty that compelled him to stay at his post, or the pain he would have endured during and after sustaining such horrific burns. Unsurprisingly, the nature of his wounds proved too severe and he succumbed later that day, dying at the age of just 20 years and two months. Hardy Falconer Parsons is buried in the immaculate CWGC cemetery at Villers-Faucon.

N.B. I was contacted in August 2019 by Dr Markus Schroeder whose great great uncle, Ernst Komander, served with the 2./Jäger 6, Jäger-Regiment 6, 195 Infanterie-Division. He tells me that regimental records show it was Jäger-Regiment 6 that led the attack on the 14th Gloucesters with the specialist flamethrowers employed by Sturmbataillon 3. Ernst Komander was wounded on the day of the attack and died of those wounds two days later. He is buried in Block 2, Grave 56 in Caudry German Military Cemetery.

Grave of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at Villers Faucon Communal Cemetery

Hardy’s effects, consisting of just a wrist ID disc and two wrist watches were sent by registered post to his father within the month.

105 Infantry Brigade war diary describing the events of 21 August 1917

The Brigade diary describes Hardy’s gallantry, commenting that he ‘was afterwards recommended for the VC for his action’. During the war many acts of bravery were put forward for the VC but subsequently rejected. However, in Hardy’s case, approval was given. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross – personally presented to his father by King George V at a ceremony on Durdham Down (Bristol) on 8 November 1917. Hardy’s father also attended the Colston Hall event on 15 February 1919 when he was presented, on his dead son’s behalf, with an illuminated address and gold watch by Lord Mayor Twiggs. The address included Hardy’s full Victoria Cross citation:

“For most conspicuous bravery during a night attack by a strong party of the enemy on a bombing post held by his command. The bombers holding the block were forced back, but Second Lieutenant Parsons remained at his post, and, single-handed, and although severely scorched and burnt by liquid fire, he continued to hold up the enemy with bombs until severely wounded. This very gallant act of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty undoubtedly delayed the enemy long enough to allow the organisation of a bombing party, which succeeded in driving back the enemy before they could enter any portion of the trenches. This gallant officer succumbed to his wounds.”

Hardy Parsons was only the second member of the Gloucestershire Regiment to receive a VC during the First World War.

Hardy Falconer Parsons VC Chapel Memorial, Kingswood School, Bath

On 23 July 1923, a tablet in his memory was unveiled in the chapel of Kingswood School in Bath and his Victoria Cross and campaign medals are held by the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, having been presented to the Gloucestershire Regiment at a ceremony in 1970 in front of what is now City Hall, attended by the Lord Mayor, Cllr Bert Wilcox.

Victor comic, 11 July 1970 – the story of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

The collection also includes a portrait photograph of Hardy in uniform; the bronze memorial plaque sent, popularly known as the “Dead Man’s Penny” to his parents after the war and his Gloucestershire Regiment collar badge. Engraved on the back of the badge are the words “Irene Randall 10 Newfoundland St., Bristol 1917”. Who she was, and why he had that, we will probably never know….

Victor comic, 11 July 1970 – the story of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

On 11 July 1970, the Victor Comic ran a cartoon story with 10 sketches on its front and back pages, recounting the story of the 14th Gloucesters action at The Knoll and to the deeds of Hardy Falconer Parsons – bringing his heroic actions to the attention of a younger audience.

Ewart Moulton Parsons

And as for the Parsons family, despite Hardy’s death, the war had not finished with them. Hardy had two younger brothers; Ewart Moulton and Lyall Ash. Lyall was born too late to serve but Ewart, born the year after Hardy, was working as an apprentice engineer at Bristol company, Brecknell Munro and Rogers in summer 1916.

Page from memorial booklet for Hardy and Ewart Parsons

He joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and by 17 July 1918, was a 19 year old Lieutenant and pilot in No.50 Training Depot Station at Eastbourne, flying his Sopwith F1 Camel fighter high above the Seaplane Station. What happened next is still unclear but his plane went into a spin and plummeted to the ground from 3000ft. Unsurprisingly, Ewart was killed instantly.

Grave of Ewart Parsons in Canford Cemetery, Bristol

His body was brought back to Bristol and his funeral held at the Old King Street Wesleyan Chapel where his father was the pastor. The coffin was borne by six RAF officers and taken on a gun carriage to Canford Cemetery, where the internment took place followed by the sounding of the Last Post.

So, in the space of eleven months James Ash and Rita Parsons had lost two of their three boys. On the base of the stone cross marking Ewart’s grave at Canford Cemetery the family also commemorated his brother, Hardy. Like so many families across the world, the Parsons’ suffered grievously in the war.

Detail on Ewart Parsons’ grave in Canford Cemetery

But, as this research is primarily based on Hardy I would like to end with a description of him, provided by his father which, when considered alongside his Victoria Cross action, shows him to have been a truly remarkable young man, a perfect example of the loss of the best of that generation:

“Hardy lived all of his life from early childhood on the same high plane of self-forgetfulness and sacrifice in his thought for and service of others”

Hardy Falconer Parsons VC (30 June 1897 – 21 August 1917)

Sources of information consulted for this article include:

Service record of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC (National Archives: WO339/73298)

105 Infantry Brigade War Diary (National Archives: WO95/2486)

14 Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment War Diary (National Archives: WO95/2486)

RAF service record of Ewart Moulton Parsons

Census returns (1901 & 1911)

Material from the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum http://www.soldiersofglos.com/

Victor Comic, 11 July 1970

London Gazette – various dates

The Kingswood Magazine, Vol. XX, No.10, December 1917

North Devon Journal, 27 August 1931

North Devon Journal, 10 November 1949

Gliddon, Gerald, VCs of the First World War: Cambrai 1917, Stroud, 2004

Second Lieutenant Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. Image courtesy Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Ref GLRRM:04750.6

On 8 November 2017 a Bristol Civic Society Blue Plaque for Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment (my local Victoria Cross recipient) will be unveiled at 54 Salisbury Road, Redland, Bristol. The date is 100 years to the day after King George V personally presented Hardy’s VC to his father, Rev James Ash Parsons at a ceremony on Durdham Downs.

Between 2014 and 2019 the Government is funding the production and placing of a commemorative stone for each and every Victoria Cross recipient of the First World War. Although Hardy Falconer Parsons lived at 54 Salisbury Road, he was not born in Bristol. So in August the government-funded commemorative stone relating to Hardy Parsons, was laid in Rishton, Lancashire.

Local historian and author Clive Burlton and I were determined to see Hardy’s strong association with Bristol and the West Country recognised. If we couldn’t have the government-funded stone in Bristol, the next best thing was to have a Bristol Blue plaque unveiled in his honour.

The grave of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at Villers-Faucon Communal Cemetery

So, during the past year we have organised for the creation of the plaque. Wednesday’s ceremony, starting at 11am, will have representatives from the Bristol Civic Society; the former Gloucestershire Regiment; the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum; the Bristol University Officer Training Corps; Kingswood School, Bath, Redland Green School and Dolphin Schools in Bristol; bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles Regiment; the Western Front Association; members of the Bristol Great War network and representatives of the Kingswood Association, whose generous donation enabled the plaque to be made and installed. Also attending are the Lord Mayor of Bristol, Cllr Lesley Alexander; the Deputy Lord-Lieutenant for the County and City of Bristol, Colonel Andrew Flint and the Dean of Bristol, the Very Rev Dr David Hoyle.

The event is open to the public so please do come along and attend if you can. I will be posting the results of my research on Hardy Parsons along with photos of Wednesday’s ceremony on my website later this week. In the meantime, it is worth reading Hardy’s VC citation to have an idea of his valour:

“For most conspicuous bravery during a night attack by a strong party of the enemy on a bombing post held by his command. The bombers holding the block were forced back, but Second Lieutenant Parsons remained at his post, and, single-handed, and although severely scorched and burnt by liquid fire, he continued to hold up the enemy with bombs until severely wounded. This very gallant act of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty undoubtedly delayed the enemy long enough to allow the organisation of a bombing party, which succeeded in driving back the enemy before they could enter any portion of the trenches. This gallant officer succumbed to his wounds.”

There should be a short film on Hardy’s action on Wednesday evening’s Points West (BBC1) from 6.30pm.

Researching the war service of Ioan Gruffud’s Great Great Uncle, Rhys Griffiths, for BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’

Back in May I spent an afternoon filming with Yellow Duck Productions for their hit BBC Wales genealogy series, ‘Coming Home’. The programme, which was shown on at 9pm on BBC One Wales on Wednesday 21 December was an hour-long special, looking at the family history of Hollywood actor Ioan Gruffud. Whilst it unlocked stories of Ioan’s royal connections it was his Great Great Uncle Rees (known as Rhys) Griffiths’ service in the Great War which I had been asked to research and explain.

Ioan Gruffud & I outside the church in Pontyberem

Rhys was the son of David and Anne Griffiths, of Meilog, Pontyberem. A keen churchgoer, at the outbreak of war he was studying to enter the ministry. He enlisted at Carmarthen in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) and was posted to 106 Field Ambulance, part of the 35th Division (made up of ‘Bantams’ who were all under the normal regulation minimum height of 5’ 3”). With his unit, he moved to France early in 1916, occupying positions in the trenches in French Flanders and Artois. Sadly, there is no surviving service record for Rhys and so his day-to-day movements can only be pieced together from his unit war diary.

63926 Pte Rhys Griffiths, 106 Field Ambulance RAMC

The war diary for 106 Field Ambulance is often short and functional, describing the routine of the subsequent months with little elaboration but noting issues involving latrines, dung heaps, a lack of coal for hot baths and too few disinfectors to help prevent scabies and lice. At the end of May 1916 this period of relative calm ended abruptly.

On the night of 30 May 106 Field Ambulance are serving in the Rue du Bois sector between the villages of Neuve Chapelle and Festubert. At this time these villages, both heavily fought over in 1915, were considered a relatively ‘quiet’ sector.

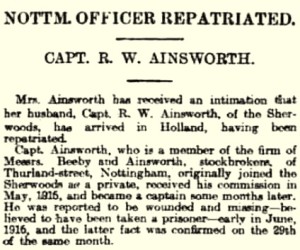

At 7.20pm that night a heavy German bombardment falls on the frontline trenches around the salient around S10.5, destroying 250 yards of breastwork trenches. Further artillery fire falls on support positions, ‘bracketing’ the area and preventing British reinforcements getting through. Under this bombardment the infantry holding this sector, W Company of 15th Sherwood Foresters, suffer heavy casualties and it is reported three officers are wounded. One of these, Captain Ralph Ainsworth is wounded twice.

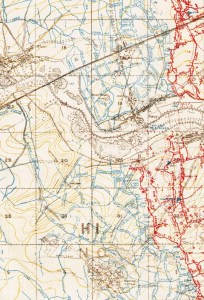

Trench map with S10.5 circled

The barrage is a precursor to a highly successful raid by the enemy. By 8.40pm, with positions destroyed and most of the Sherwood Foresters wounded, German troops attack, penetrating the right flank of the position and taking a number of men prisoner. By 10.10pm men of the 14th Gloucesters and 18th Lancashire Fusiliers had re-established British control of the salient.

By then, Rhys had been killed. The exact circumstances surrounding his death are provided by a letter written by Frank Fairfax, the Chaplain of the Field Ambulance, to Rhys’ father which was later published in The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser of 8 September 1916:

Dear Mr Griffiths, I have to break the sad news to you of the death of your son, Rhys, on the night of 30 May. In the bombardment of the trenches there were many wounded, and he and his friend, Dugdale, were together giving first-aid and carrying the wounded back to safety. As I understood it was while Rhys and Dugdale were attending the wounded officer that a shell burst which killed Rhys, but left Dugdale unharmed except for a severe shock. When he is well enough he will be writing to tell you about it. But there is no doubt order tramadol online 180 that Rhys showed great bravery, and thought not of himself in his noble devotion to duty. I knew him and loved him. He was known to be a splendid comrade and a true Christian. Often he would sing to us his Welsh songs and hymns.

The German raid was very well planned and executed. Raids such as this were a common enough event, even in ‘quiet’ sectors. Their usual aims were to kill the enemy, gather intelligence on defences and, if possible, capture prisoners who could be interrogated for additional information.

A report written the following day by Lt Colonel RNS Gordon, 15th Sherwood Foresters details two Officers and thirty-four Other Ranks still unaccounted for. A subsequent report provides a detailed narrative of events and lists Officers and men who showed gallantry during the raid. First on the list is Captain Ainsworth (the twice wounded officer) who the report describes as ‘although wounded twice refused to be moved and stayed with his Company until the end. He displayed remarkable coolness and apparently only gave the orders to withdraw to the flanks as a last expedient.

He further took steps to see that all documents and the logbooks were sent to Headquarters on realizing the gravity of the situation.

He is, I regret, still missing.’

Nottingham Evening Post – Monday 22 April 1918

In fact, he stayed missing – at least to the British. Records show Captain Ainsworth was captured by the raiding party. He was held by the Germans in Officers’ Detention Camps at Crefeld and Holzminden until April 1918, when he was transferred to Holland, finally being repatriated in December of that year. Notification of his transfer to Holland reached the Nottingham press on 22 April (shown to the left). A Facebook page ‘Small Town, Great War. Hucknall 1914-1918’ gives more detail on Captain Ainsworth here.

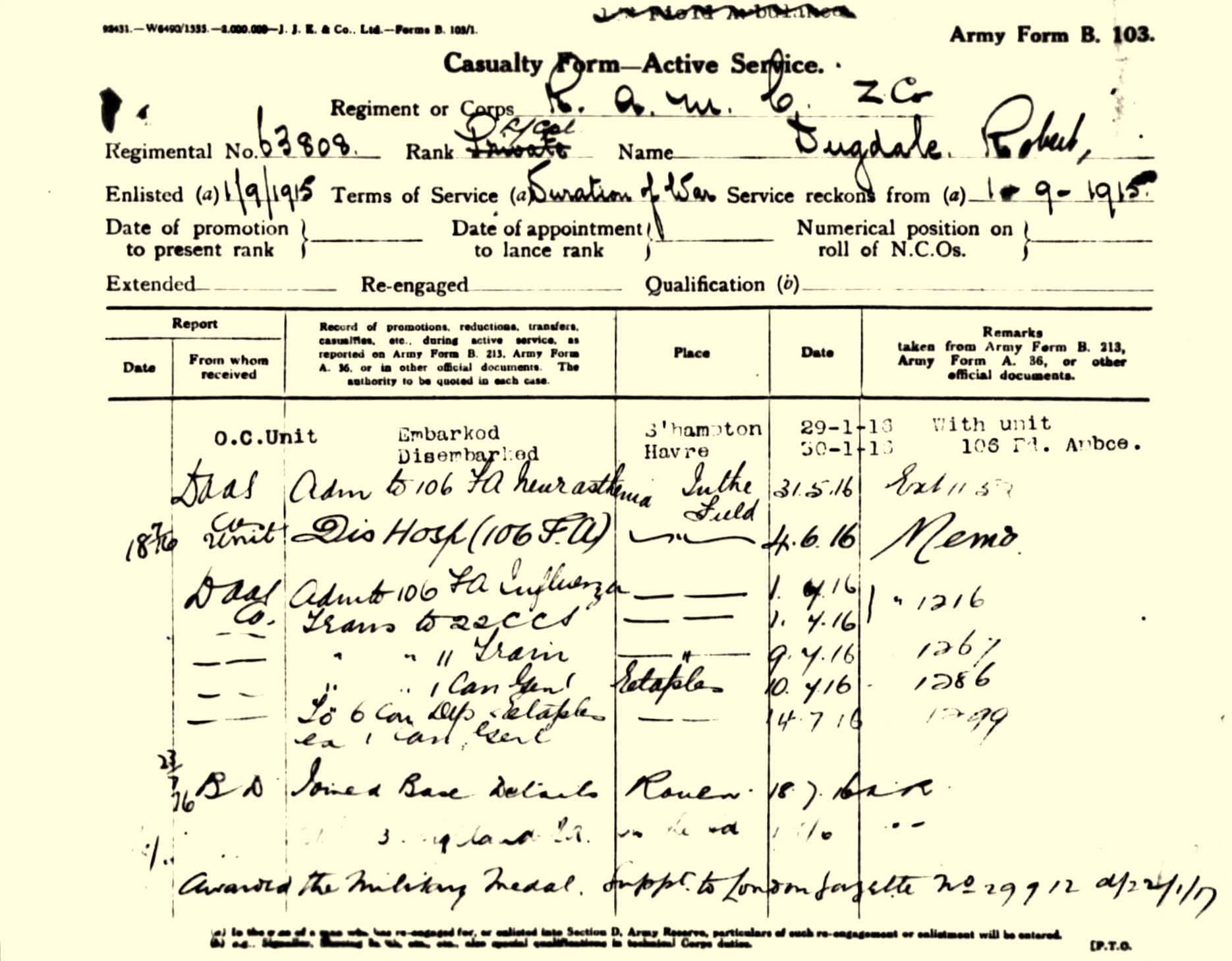

As the chaplain’s letter describes Rhys and Dugdale attending a wounded officer when Rhys is killed, there is a good chance the officer was Ainwsworth. The letter also describes Rhys’ RAMC comrade, Private Robert Dugdale, being severely shocked. Dugdale’s pension record survives and confirms the chaplain’s description of events. He was admitted to the Field Ambulance as a casualty that night, suffering with neurasthenia. Dugdale makes a full recovery, serves through the Somme, Passchendaele and the 1918 battles, ultimately surviving the war. Having served nearly four years he was discharged in July 1919. Dugdale was awarded the Military Medal in January 1917, probably for good work during the Battle of the Somme.

Casualty Form from Robert Dugdale’s Pension Record showing his admission to the Field Ambulance with neurasthenia

Rhys Griffiths was the first death suffered by 106 Field Ambulance since their arrival in France. The other two men known to be associated with his death, Private Robert Dugdale and Captain Ralph Ainsworth, both survived the war. Such is the way luck can play a part in surviving time in the trenches. Despite it being a tragic story, it was a satisfying experience to talk Ioan and his father Peter through Rhys’ all too brief period of time on the Western Front. Another family now aware of their link to the Great War.

Rhys is buried in St. Vaast Post Military Cemetery, Richebourg L’Avoué alongside the men of 14th Gloucesters and 15th Sherwood Foresters who also died on 30 May 1916. Remembering them all.

Grave of Pte Rhys Griffiths, 106 Field Ambulance RAMC at St. Vaast Post Military Cemetery, Richebourg L’Avoué

Link to BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’ page: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b086xl8v

Researching the war service of David Emanuel’s grandfather, John Leslie Emanuel, for BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’

In June I spent a day in Merthyr Tydfil filming with Yellow Duck Productions for their hit BBC Wales genealogy programme, ‘Coming Home’. Having worked with Yellow Duck on a previous series I was asked to research the wartime service of John Leslie Emanuel, grandfather to the fashion designer David Emanuel.

As was revealed in tonight’s broadcast, David never met grandfather who drowned in a tragic accident in December 1939. Whilst aware of his grandfather’s drowning, David had little knowledge of his wartime military service. We had a lucky start in that his grandfather’s service record survived. Using this and extant unit war diaries I was able to show David where his grandfather had served.

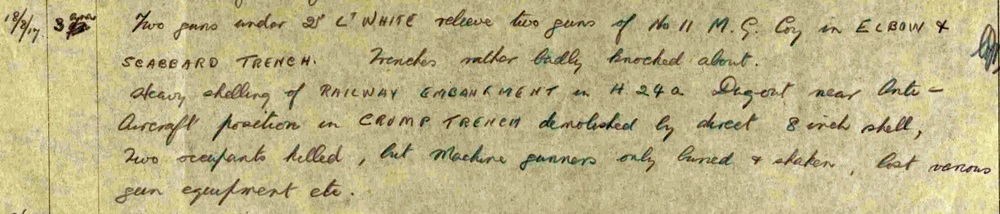

Trench map extract of the Roeux – Monchy area – positions occupied by 234 Machine Gun Company in summer 1917. Crump Trench runs just to the south of the railway line in the area west of the village of Roeux.

John Leslie Emanuel enlisted in February 1916 in the Sussex Yeomanry and proceeded to France in September of that year, joining the 10th Battalion Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment). He soon transferred to 124 Machine Gun Company, spending six months on the Western Front, mostly in positions facing the enemy on the Messines Ridge. His active service was interrupted by his evacuation back to Britain, suffering from P.U.O. (pyrexia of unknown origin).

Four months later, having recovered, been promoted to Corporal and now serving with 234 Machine Gun Company, he again proceeded overseas. The unit war diary recorded the men swam in the sea off Le Havre (noting the water was warm!) before moving to the Arras sector. The Battle of Arras had ground to a bloody halt in mid May 1917 but isolated actions continued into the summer. The main British effort for summer 1917 was focused on endeavours in Flanders. However, this did not mean that 234 MGC had an easy time of it in Artois.

Extract from 234 Machine Gun Company War Diary 18 August 1917. Held at National Archives, Kew under Ref: WO95/1472/2 and reproduced with their permission.

The war diary is illustrative of the kind of routine and boredom of trench life but occasionally reveals periods of terror. 234 MGC was serving either side of the River Scarpe, providng support to the infantry occupying positions north of Monchy-le-Preux and in the village of Roeux, scene of bitter fighting in April and May. On 18 August an 8 inch German shell demolished a dug out near an anti-aircraft position in Crump Trench. Two of the occupants were killed outright but the machine gunners survived, despite being buried and badly shaken. A CWGC cemetery, named after Crump Trench now sits on the trench location.

A month later the company moved up to Flanders to take their part in the British offensive – the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). What struck me when looking at David’s grandfather’s story is that he was sent to a Corps rest camp for the entire period 234 MGC was in action near Langemarck. It is possible this period of rest was astonishingly good luck on his part. However, with the unit having undergone a fortnight’s training prior to their deployment north, it seems a strange time for a Corporal to be given leave. Detailed records are missing but it may have been that, after the rigours of the Arras sector, he simply needed a break. Despite popular modern misconceptions there was an appreciation of mental fatigue and it was understood that often men needed a rest away from the guns to recover. Put simply, no man whose mind was in a fragile state would have been of any use in the artillery war that dominated the Flanders battles. This omission may well have saved his life as the company inevitably took casualties when engaged in battle. Upon leaving Flanders 234 MGC returned to the Arras sector. In mid-December 1917 John Leslie Emanuel was sent back to Britain as a candidate for a commission. He never saw active service again, being discharged before the armistice.

David Emanuel gave an interview to Wales Online about his participation in ‘Coming Home’: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/whats-on/film-news/david-emanuel-war-hero-granddad-8149943

I have recently received the TX card for the upcoming BBC Arts documentary ‘War of Words – Soldier Poets of the Somme’. It will be shown on BBC Two on Saturday 15 November at 9.45pm.

The 90 minute documentary which I worked on as historical consultant in 2013 follows literary figures who took part in the Battle of the Somme.

The documentary, presented by Peter Barton and directed by Sebastian buy ambien online bluelight Barfield, has its own dedicated page containing information, Director’s notes and preview clips: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04pw01r

BBC iPlayer has a dedicated page showing an anthology of animated poems using the work of Robert Graves, David Jones, Siegfried Sassoon, W.N. Hodgson and Isaac Rosenberg to relay the experiences of these poets during the battle. See http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p02b11yw/the-somme-in-seven-poems

Preview of ‘War of Words – Soldier-Poets of the Somme’ at Bristol’s Watershed on 5 November 2014

I spent much of 2013 working as historical consultant for the upcoming BBC Two documentary ‘War of Words – Soldier Poets of the Somme’. A special preview is being shown as part of Bristol 2014 at the Watershed at 1800 hrs on 5 November. The 90 minute film will be shown in its entirety followed by a short break and then what we hope will be a lively panel debate. Panellists are myself, Peter Barton, the film’s director Sebastian Barfield, Richard van Emden and Jean Moorcroft Wilson. The evening is now fully booked.

The film’s presenter Peter Barton at Regina Trench on the Somme. It was here that J.R.R. Tolkien, creator of Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit buy legit tramadol online served in October 1916.

The film follows literary figures who took part in the Battle of the Somme. As the film’s description notes “More poets and writers took part in the battle of the Somme than any other battle in history, among them Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, David Jones, and JRR Tolkien. This new BBC film looks at how these men served in the same trenches, fought in the same attacks and wrote poetry and prose that has shaped the way people remember the Great War.”

Edit (4 November): I have now heard that broadcast date will be Saturday 15 November but have no TX Card or further details. I will update my website and Twitter feed when I know this.

Links:

http://www.watershed.co.uk/whatson/6193/war-of-words-soldierpoets-of-the-somme/

http://www.ideasfestival.co.uk/2014/events/bbc-preview-war-of-words-soldier-poets-of-the-somme/

http://www.bristol2014.com/whats-on/film-bbc-preview-war-of-words-soldier-poets-of-the-somme.html#.VE90sFfvZ8E

Private William Fry, 53rd Battalion AIF at Fromelles for BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’ with Robert Glenister

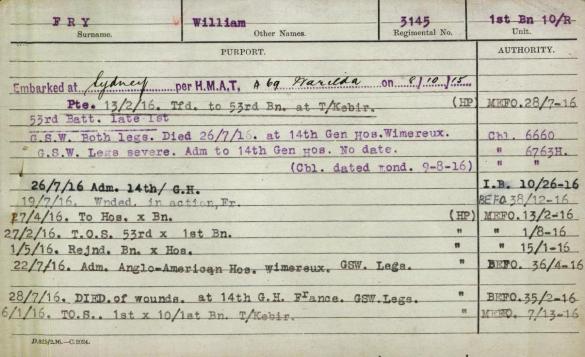

In October I was approached by Yellow Duck Productions to help with an episode of their BBC Wales series ‘Coming Home’. I was to conduct research into the wartime service of William Fry, a miner from Penclawdd in the north of the Gower Peninsula outside Swansea. William Fry was a relative of Spooks and Hustle actor Robert Glenister.

Talking through William Fry's wartime service with Robert Glenister in St Gwynour's Church, Penclawdd

William Fry left Wales in 1914, en route to a new life in Australia. At sea when war was declared, he arrived in Sydney in late August 1914. By the end of July 1915 William had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force and sailed from Sydney on 8 October 1915 bound for Egypt. Whilst at Tel el-Kebir in February 1916 he transferred to the 53rd Battalion, a strange mix of Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion and new, inexperienced reinforcements from Australia. The battalion, along with the 54th, 55th and 56th formed the 14th Infantry Brigade, part of the Fifth Australian Division.

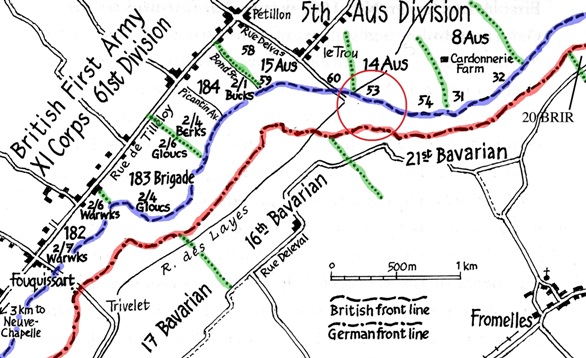

The battalion arrived in Marseille at the end of June and after a journey north through France entered front line trenches opposite Fromelles on 10 July. It was customary practice to provide new units with time to ‘bed in’ in a quiet, nursery sector in order to get used to the routines and peculiarities of trench life. No such luxury was afforded William’s 53rd Battalion as, within a week, they were selected to be at the vanguard of a strong attack against German trenches at Fromelles. After a day’s rest in billets the 53rd Battalion were back in the front line on 17 July.

Map showing frontage for the Fromelles attack. The position of William Fry’s 53rd Battalion AIF is circled.

The plan required an initial softening of German defences by artillery bombardment and the attacking infantry to advance at 1800hrs in broad daylight, capturing and seizing two lines of trenches. At 1743hrs the first wave moved out into No Man’s Land, followed 100 yards later by the next wave. At Zero Hour (1800hrs) the Battalion charged and captured the first two lines of trenches as planned but then, contrary to the agreed plan, pushed on ‘200 yds further to hold back enemy’s bomber who were counter-attacking’.

Members of William Fry’s 53rd Battalion prior to ‘hopping the bags’ on 19 July 1916. Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial (ID Number A03042).

The positions were held through the night but determined German counter attacks coupled with an exposed right flank forced the 53rd back across No Man’s Land to their starting position at 0930hrs on the 20th. Casualties for the operation totalled 625, an extraordinarily high figure which included the commanding officer. The attack at Fromelles was a complete disaster; losses for the Fifth Australian Division were over 5500 men. At some point on the 19th July William Fry was badly wounded; his medical records show he received GSW (Gun Shot Wounds) to both legs. He was evacuated along the casualty clearance chain, ending up at No.14 General Hospital at Wimereux on the channel coast. Sadly, William Fry died of his wounds at 4.15pm on 26 July 1916 and is buried at Wimereux Communal Cemetery.

Extract from William Fry’s service record showing his movements from leaving Sydney in October 1915 to his wounding on 19 July and death at No.14 General Hospital, Wimereux.

Prior to the day’s filming at St Gwynour’s Church in Penclawdd Robert was completely unaware of this part of his family’s history. Using the Battalion war diary and maps I was able to talk through William’s service and the 53rd Battalion’s attack on Fromelles. In many ways it was a typical example of the global scale of the war. A miner, all 5ft 2 ¼ inches of him, seeking a new life in Australia but enlisting for King and Country and travelling all the way back to Europe to do ‘his bit’. Fromelles was an ill-conceived diversion against tactically superior German forces but this should not detract from the endeavour, patriotism or simply a longing for involvement in the war of William Fry and his mates in the 53rd Battalion AIF. It was especially poignant leaving the church and walking up the path to my car. It is lined with lime trees – replacements for the original trees planted in the 1920s to commemorate local men lost in the war.

Robert Glenister gave an interview to Wales Online about his participation in ‘Coming Home’: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/showbiz-and-lifestyle/television-in-wales/2012/12/08/hustle-star-robert-glenister-on-his-welsh-ancestor-s-wartime-heroism-91466-32377072/

Following in the footsteps of Godfrey Hinnels with Hugh Dennis for ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’

Last January I spent three days filming with Hugh Dennis for Wall to Wall’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ series. We were following in the footsteps of Hugh’s maternal grandfather, Godfrey Parker Hinnels. Godfrey served with the 1/4th Battalion Suffolk Regiment from Spring 1917 until his transfer to the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment in March 1918. Despite having just over a year on active service Godfrey certainly saw his share of action, going ‘over the top’ at Arras and Ypres as well as fighting during the German Kaiserschlacht and the defence of Wytschaete in April 1918. This article is designed to provide more information on those units and their actions covered in tonight’s episode.

Last January I spent three days filming with Hugh Dennis for Wall to Wall’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ series. We were following in the footsteps of Hugh’s maternal grandfather, Godfrey Parker Hinnels. Godfrey served with the 1/4th Battalion Suffolk Regiment from Spring 1917 until his transfer to the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment in March 1918. Despite having just over a year on active service Godfrey certainly saw his share of action, going ‘over the top’ at Arras and Ypres as well as fighting during the German Kaiserschlacht and the defence of Wytschaete in April 1918. This article is designed to provide more information on those units and their actions covered in tonight’s episode.

Battle of Arras

Godfrey’s Suffolk battalion formed part of 98th Brigade, 33rd Division. It did not participate in the initial advance on the morning of 9 April 1917 but was moved up close to the front line on 12 April, occupying a position on the road between Henin-sur-Cojeul and Neuville Vitasse, the scene of bitter fighting on the battle’s opening day. The battalion war diary records ‘A great deal of burial and salvage work was done by the battalion in the vicinity of the trenches in front of the Hindenburg line’. Godfrey’s initiation into active service can hardly have been harsher; searching through the blanket of snow carpeting the battlefield for men killed a few days earlier. There followed a move into the Hindenburg Line itself for a spell in the trenches before the battalion’s major effort in the Arras offensive.

Hugh Dennis and I go through the Suffolks attack at the sunken lane in the Sensée valley. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

At 4.45am on 23 April 1917 a huge British artillery onslaught fell on to the German trenches signalling the start of the Second Battle of the Scarpe. Godfrey’s battalion was tasked with bombing their way down 2,300 yards of both front and support trenches of the Hindenburg Line to the Sensée River. Despite the support of tanks and artillery this was still a highly ambitious task, being prosecuted down a strong system of trenches, specially designed for defence. A deep tunnel ran under the support trench offering accommodation, headquarters and stores. The initial advance was spectacular with the Suffolks reaching a sunken road between Croisilles and Fontaine-les-Croisilles within two hours. Just 200 yards short of their objective they then came under sustained German fire. Later that day a strong German counter-attack pushed them back in both trenches – they ended the day close to the morning’s starting position. Despite taking a remarkable 650 German prisoners in the initial advance the battalion suffered over 300 casualties (about 50% of the battalion strength). This bloody day’s fighting is chronicled in great detail in ‘From the Somme to the Armistice’, the memoirs of Captain Stormont Gibbs MC, an officer in the 1/4th Suffolks.

The village of Fontaine-les-Croisilles bathed in evening sunshine. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

Passchendaele

Following their mauling in the Hindenburg Line the battalion’s losses were made up with reinforcements. Back to fighting strength they moved north to the coast before heading to Ypres to take part in the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). The battle had commenced on 31 July but unexpectedly heavy rainfall in August coupled with the destruction of the delicate Flemish drainage system by millions of artillery shells had reduced the landscape to a shattered Stygian moonscape of overlapping shell holes. Any advance had been limited but September’s improvement in the weather gave the battlefield time to dry out. Ironically, considering the common perceptions of Passchendaele, dust became a problem with roads and tracks watered regularly to restrict dust clouds caused by passing troops and transport.

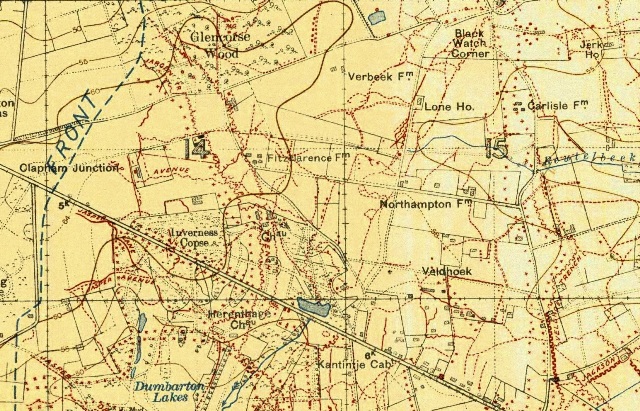

It was into this landscape that the Suffolks found themselves in September 1917. By 11.30pm on 25 September they were holding a line of trenches on the infamous Gheluvelt Plateau running between Fitzclarence Farm and Glencorse Wood, close to Polygon Wood. The plan was for the battalion to leave their positions, advance towards Black Watch Corner where a line of shell holes marked the British front line and join in the general attack at Zero Hour, 5.50am on the 26th.

The Suffolks were shelled prior to Zero Hour and heavy casualties sustained. The Battalion War Diary makes for depressing reading: ‘The heavy shelling, thick mist and darkness caused confusion and it was impossible for the men to keep touch but Platoon rushes were made and some Platoons made progress.’ Any great advance was impossible and by day’s end the battalion had only managed to advance to a line near Black Watch Corner. The battalion had achieved little and lost around 250 men in the process.

Extract from British trench map dated 14 September 1917 showing the Suffolks' battlefield - Fitzclarence Farm, Glencorse Wood and Black Watch Corner can be clearly seen.

The Passchendaele section was not broadcast but has been included as ‘unseen footage’ on the ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ magazine’s website here: http://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/footage/13822.

Winter 1917/1918 & Talbot House

The battalion took no further part in offensive action but spent the next six months in and out of the line on the Passchendaele ridge. When not in trenches the Suffolks were at rest in camps close to the small town of Poperinghe. Whilst not documented, it is highly likely Godfrey would have visited Talbot House – the “Every Man’s Club” situated in the bustling town’s heart. At our first meeting I had described Talbot House (also known as Toc H) to Mark Bates, the director of Hugh’s episode, and suggested a visit. It would be a good buy alprazolam .5 mg opportunity to show a typical soldier’s experiences when out of the line. We visited during our recce in December 2011 and, like so many before, I could tell Mark was taken with Talbot House. The house has a unique atmosphere rarely encountered in other buildings and I was delighted to see the Talbot House section so prominent in the final edit.

Spring 1918

On 1 March 1918 Godfrey headed south to the Somme where he joined the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, part of the 21st Division, holding trenches near the village of Épehy, once again opposite the Hindenburg Line. The exact reason behind his transfer is not documented but coincides with the 1/4th Suffolks becoming a pioneer battalion. It may have been that Godfrey’s skills were required more in a frontline infantry battalion as opposed to a pioneer battalion. He was soon into action as the Germans launched their Spring Offensive (Kaiserschlacht) on 21 March. Deluged with gas shells the Lincolns were attacked under cover of ‘a heavy white mist’. A day of desperate fighting followed with positions held around Chapel Hill before relief and retirement across the 1916 Somme battlefield. On 1 April the Lincolns entrained north to Flanders but hopes for a rest were short lived.

On 9 April a German attack south of Armentières heralded the start of the Battle of the Lys. A huge hole was punched in the Allied line and with his southern flank crumbling General Plumer, commanding the Second Army, ordered a withdrawal from the Passchendaele Ridge back to positions close to Ypres and the Yser Canal. The situation was desperate.

Wytschaete (now renamed Wijtschate) under a heavy sky. This view is looking north-east towards Staenyzer Cabaret crossroads. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

On the evening of 12 April with the battalion at less than half strength the 1st Lincolns were sent to defend the village of Wytschaete (nicknamed Whitesheet by British soldiers), holding a line between Staenyzer Cabaret crossroads and Bogaert Farm. Messines, directly to the south, had fallen two days previously and with Wytschaete the next village along the ridge an attack was almost inevitable. At 4.30 am on the morning of 16 April a heavy artillery bombardment pounded the British front line, the village and all approaches, lasting for 70 minutes. The official account of the operation details the subsequent events:

“Under cover of a dense fog the enemy attacked on the flanks of the battalion, and succeeded in breaking our line just North of the STANYZER CABARET Cross Roads, and at PECKHAM. Strong parties of the enemy then wheeled inwards and attacked both flanks of the battalion…Owing to the dense fog and bombardment it was impossible to get a clear idea of the situation and the Companies did not know they were attacked until the enemy appeared at close quarters. Fighting under every disadvantage, as the fog denied them the full use of Lewis Guns and rifles and made it impossible to locate the enemy, the battalion stood firm, and fought it out to the last. No officer, platoon post or individual surrendered and the fighting was prolonged until 6.30 am. Ample evidence of this is provided by the Commanding officer [Major Gush MC] and Battalion H.Q. who made a last stand at the Cross Roads, and did not leave there until 7 am. They, a mere handful of men, withdrew slowly, fighting all the way through WYTSCHAETE WOOD.” [National Archives Ref: WO95/2154]

The Lincolns had provided a magnificent display of defensive fighting in tremendously difficult conditions. During the action Godfrey was wounded in his index finger – a wound that prevented his return to frontline service. The following day a mere 5 officers and 82 other ranks were relieved to be joined by a further 21 stragglers who had become attached to other units during the fighting. Having gone into action with over 400 men, the Lincolns’ stubborn defence had been bought at a high price – the casualty rate was nearly 75%. The losses were not in vain as Brigadier General Cater commanding Godfrey’s Brigade noted how the ‘hard fighting left the enemy disorganised and unable to consolidate; and materially assisted the counter-attack delivered in the evening.’

At Wytschaete reading the account of the 1st Lincolns stand on 16 April 1918. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

Matching soldier’s reminiscences to actual actions can often be problematic but by studying Godfrey’s war service it soon became clear his story of fighting Germans on a hilltop must have related to the defence of Wytschaete. It was a remarkably satisfying conclusion to stand with Hugh Dennis on the same ground where his grandfather fought so gallantly ninety four years earlier.

My thanks to Paul Nathan for his agreement to use his photographs from filming, Mark Bates, Mike Robinson and all at Wall to Wall for their help plus Peter Barton for various maps & documents.

If you would like to read more about these battles and places then a very short suggested reading list is included below:

- Peter Barton with Jeremy Banning, Arras – The Spring 1917 Offensive in Panoramas including Vimy Ridge and Bullecourt (Constable, 2010)

- Jonathan Nicholls, Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917 (Leo Cooper, 2005)

- Peter Barton, Passchendaele – Unseen Panoramas of the Third Battle of Ypres (Constable, 2007)

- Paul Chapman, A Haven from Hell – Talbot House, Poperinghe (Cameos of the Western Front) (Pen & Sword, 2000)

- Chris Baker, The Battle for Flanders: German Defeat on the Lys 1918 (Pen & Sword, 2011)