Archive for 2013

Lecture at Dunham Massey Hall – National Trust property

Earlier this autumn I spoke to the staff and volunteers at Dunham Massey Hall, a National Trust property in Cheshire. I had been approached some months before to help with their ambitious First World War project ‘Sanctuary from the Trenches’ which will see the hall will open its doors on 1 March 2014 as Stamford Military Hospital, the convalescent hospital in which 281 soldiers were treated between April 1917 and January 1919. Lady Stamford’s original plan to turn the hall over for use as a hospital for officers was altered, perhaps due to the sheer number of wounded men, and when the doors opened in April 1917 the hospital cared solely for ‘Other Ranks’.

My role in this project was to interpret the wealth of material gathered by the team of volunteers, pick a representative sample of men from those chosen and use their stories in a lecture to not only explain the conduct of the war in 1917-18 but also elaborate on the daily routine of trench warfare, evacuation of sick and wounded and medical treatment received by the men. The information uncovered by volunteers was prodigious; there was no shortage of material related to the soldiers’ stay at Stamford Military Hospital. What was lacking was an appreciation of where those men had come from, in what actions they had fought and been wounded and what happened to them after their recuperation.

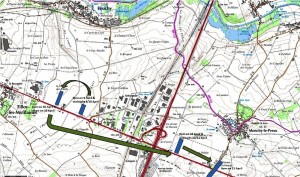

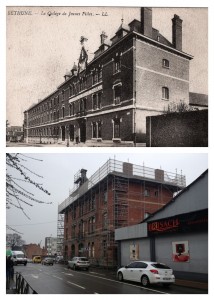

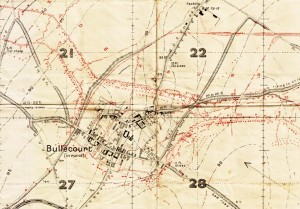

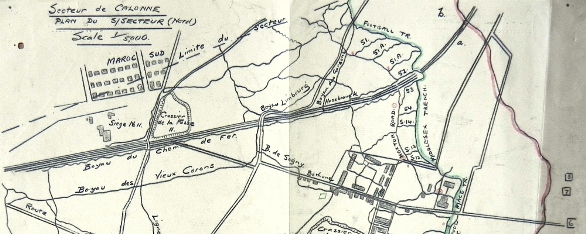

Bullecourt trench map extract. Two of the men who recuperated at Stamford Military Hospital were wounded here on 3 May 1917.

Casualties studied included a man of the 11th Rifle Brigade wounded near Havrincourt Wood in the push to the Hindenburg Line in early April 197, two men caught up in the Hindenburg Line itself at Bullecourt in May and a French Canadian wounded on Vimy Ridge. I was also able to use descriptions from my research into the Battle of Arras to illustrate the actions at Fampoux and Roeux in which a soldier of the 2nd Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment was badly injured. Moving northwards to Flanders I was able to look at the Battle of Messines (June 1917) with Private John Ditchburn, 9th Yorkshire Regiment, wounded close to Hill 60 on 7 June and two further casualties from the Third Battle of Ypres. Sources used included Medal Index Cards, Service Records (where available) and Census Returns. By scouring Brigade, Division and Corps files I was able to find appropriate maps to illustrate the exact area where the men had fought.

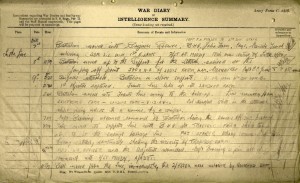

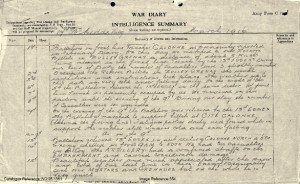

War Diary extract from 2nd Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment) for October 1917. One of the men who had been wounded at Arras, recuperated at Stamford Military Hospital, returned to the front and was killed in the Passchendaele offensive.

I was also keen to include soldiers wounded whilst not taking part in any major set-piece battle but in the daily business of merely ‘holding the line’. This offered a good opportunity to show the limitations of available documents. None of the men I researched were named in unit war diaries and so, in many cases, it was an educated guess as to the site of his wounding. Private William Johnstone, 1st Gordon Highlanders was hit by shrapnel in spring 1918 close to the city of Arras but from sources available I was unable to identity which day. His was a particularly sad story; after recuperating for over two months at Dunham Massey he was found to have shrapnel embedded deep in his head. Over time his condition deteriorated and he died of a cerebral abscess in hospital in Manchester. The final man I focussed on was even harder to research; Private Jenkins of the 1st Gloucestershire Regiment was wounded at some point during the autumn of 1918, the ‘Last Hundred Days’ of the war. His full identity remains unknown with neither christian name or regimental number noted in the records extant. I was keen to contrast this with some of the earlier soldiers I had researched where I had been able to provide highly detailed information.

Having prepared the research on these men I spoke at Dunham Massey Village Hall to two groups of volunteers on 18 September. I was heartened by the audience’s reaction, not only by the enthusiasm shown but also the interest in the men and the ‘Sanctuary from the Trenches’ project. I look forward to returning to Dunham Massey to see how the information has been used and what the ornate saloon will look like with furniture replaced with stark hospital beds. I would like to thank Charlotte Smithson and all those who work and volunteer at Dunham Massey for their help and enthusiasm with this project.

Our forthcoming project Sanctuary from the Trenches; a Country House at War tells the story of how Dunham Massey Hall became the Stamford Military Hospital, caring for 281 soldiers. Our collection gives us some information about the soldiers that stayed at Dunham, but we wanted to know more about their lives before they were treated here. Using our archive and other resources, Jeremy pieced together their stories. Jeremy’s respect for those that fought during the First World War made for a heart-warming lecture. He talked us through what our soldiers had experienced and left us feeling fondly affectionate for the brave souls who were cared for here. Over 100 volunteers attended the lecture and it was a big hit with them all – they haven’t stopped talking about it since. It provided the background of information for our volunteers needed in order to contextualise the Stamford Military Hospital’s role in the First World War. We’ll be asking Jeremy back, without a doubt!

Charlotte Smithson, Volunteer Development Manager at Dunham Massey

An interview with me discussing my research is available to view below:

For those interested my lecture is available in full here: http://vimeo.com/75168130

A dedicated page on the National Trust’s website with further details is available here: Sanctuary from the Trenches http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/article-1355804816003/

Further testimonials:

‘Jeremy Banning’s knowledge of the First World War is second to none and he is as good a presenter as you could wish for. A star attraction, I would suggest. So to have him come to talk to us Volunteers was a real treat. The presentation was so revealing and full of fascinating tales of soldiers directly connected to our Property’.

‘I am still buzzing and it is down to Jeremy Banning! Such a wonderful talk – please pass on my thanks.’

‘I want to thank you for enabling me to have and enjoy the privilege of attending Jeremy Banning’s presentation this morning. The whole experience was informative, exciting, thought provoking, uplifting and at the same time humbling. Jeremy’s enthusiasm and knowledge, for me and I am sure, all the other volunteers attending, made it a most memorable morning and I thank you, very sincerely, once again.’

‘A superb morning at Dunham Village Hall with Jeremy Banning – he really brought our soldiers to life, with such affection too. It was a privilege to attend’

On Saturday 19 October I will be speaking about the ‘The Battle of Arras – April/May 1917’ at the autumn seminar of the Worcestershire & Herefordshire Branch Western Front Association. The event will be held at the University of Worcester, Henwick Grove, Worcester, WR2 6AJ. Doors open at 12.00pm with my lecture starting at 1.00pm. Richard van Emden will be speaking at 3.15pm on ‘Boy Soldiers of the Great War’. Full details can be found on the attached PDF flyer. Please click to open and download: Worcestershire & Herefordshire WFA Seminar poster

Copies of ‘Arras – The Spring 1917 Offensive in Panoramas including Vimy Ridge and Bullecourt’ and Richard’s ‘Boy Soldiers of the Great War’ will be available to buy.

To buy tickets please call the Worcestershire & Herefordshire Branch on 01905 774797 or e-mail whb.wfa@hotmail.co.uk. The deadline for bookings has now been extended to 4 October.

I recently led a one day trip to the Arras battlefields for three generations of a soldier’s family (nephew, great-nephew and great-great nephew). I had been asked to research the actions of Private Horace Pantling, 10th Battalion Loyal North Lancashire Regiment around Arras. Horace’s Battalion formed part of 112th Brigade, 37th Division and will be forever known with the actions on 11 April around the small hilltop village of Monchy-le-Preux.

After a general briefing on the battle and a visit to the Carrière Wellington to take a tour around the underground system we headed out on the battlefield, starting on the British front line on 9 April 1917, the first day of battle. Following the arrow straight Arras-Cambrai road I explained the attack British assault up to the Brown Line near Feuchy Chapel. From then I was able to use a series of maps from the 37th Division files that showed positions of units every three hours for the first three days of battle. We followed the 10th Loyal North Lancs in their advance up the road in the early morning of 11 April. With the neighbouring 111th Brigade attacking the village of Monchy it was down to the 112th Brigade to take the Green Line to their right.

The Battalion war diary records that on moving to their assembly positions for the 5.30am advance the 10th Loyal North Lancs immediately were ‘met with very heavy Machine Gun and Shell fire’. However, their assault on the trenches around the La Bergère crossroads was successful and positions were consolidated. Casualties were estimated at 13 Officers and 286 men for the Battalion’s part in the opening stages of the Arras offensive. A number of the Battalion’s dead now lie in the nearby Tank Cemetery.

Tank Cemetery, Guemappe where many men of the 10th Loyal North Lancs killed on 11 April 1917 now lie

As we looked over the gently rising fields near Monchy it was hard to imagine the scene in the early morning of 11 April 1917. We had been blessed with a clear, spring day. The British troops who performed so magnificently that day 96 years ago did so with heavy snow and a chill wind across the battlefield.

Having been taken out of the line for a rest they were next in action on 23 April during the 37th Division’s assault on Greenland Hill during the Second Battle of the Scarpe. The war diary made grim reading with very little gain possible owing to the German occupation of the Chemical Works at Roeux on the right. On the 27th orders were received to attack Greenland Hill at dawn the next day. At 4.27am on 28 April that Battalion attacked and reached a trench that had been begun by the enemy. The war diary records that ‘By this time the Battalion had suffered heavily and only one officer was left’. Once more suffering from enfilade fire from the Chemical Works, the Battalion dug in. The attack was yet another failure in the face of superb German resistance.

28 April 1917 map of Greenland Hill overlaid on to Google Earth. Map taken from 37th Division War Diary, National Archives Ref: WO95/2513

It was during the actions on the 28th that Horace Pantling was killed. Horace, like so many British killed in the latter stages of the Arras offensive, has no known grave and is commemorated on the Arras Memorial. We were able to stand close to the positions where the 10th Loyal North Lancs assaulted and then, after a circuitous journey walk close to the spot where the Battalion dug in. It is one of those strange twists of fate that the junction of the A1 and A26 motorways now stands slap-bang right on Greenland Hill. Only by heading toward Plouvain and turning down a narrow track could we get close to the spot where the Battalion ended up. Sadly, the exact spot is now accessible only by driving on the slip road from the A1 to join the A26.

Arras Memorial where Horace Pantling and a further 35,000 servicemen from the United Kingdom, South Africa and New Zealand who died in the Arras sector between the spring of 1916 and 7 August 1918 are commemorated

We had visited Horace’s name on the Arras Memorial earlier in the day so it seemed a suitable place to end the tour. What struck me, as ever, was the small distances – easily covered in a minute or two in the car – that took so much effort to capture and consolidate in spring 1917. The British casualty figures for the Battle of Arras make sobering reading; 159,000 casualties in 39 days – averaging 4000 casualties per day. Despite countless visits to the battlefields such scale of loss in concentrated areas still both appals and moves me. Horace Pantling was one of those casualties but his name is certainly not forgotten and three generations of his family now know the ground over which he fought and was ultimately killed in April 1917.

“Thank you so much for organising such an excellent day in and around Arras last week. We all hugely enjoyed having your professionalism, enthusiasm and knowledge on tap, and your organisation was faultless! My father came away thrilled with the trip, and that was all I could have asked.” Nigel Pantling

A superb resource for those interested in the 10th Loyal North Lancs is Paul McCormick’s website http://www.loyalregiment.com/.

The internet is a wonderful thing; for anyone interested in a certain battalion or unit it is now possible to hammer a few key words into a search engine and find all sorts of information about their part in major, set-piece battles. Forums and discussion groups also have their place. Some regimental museums have even transcribed all of their battalion war diaries, making them available online for free.

Extract from the 17th Middlesex Regiment War Diary. Reproduced with permission of National Archives, Ref: WO95/1361

Libraries, regimental archives and the National Archives all have information available to help understand events. However, what of the vast majority of time spent not going ‘over the top’ or taking part in the next ‘Big Push’? What of the less-well chronicled, monotonous but necessary routine of trench warfare?

It can be an immensely satisfying task to follow a unit’s movements around the battlefield; this is often undertaken as part of a family pilgrimage or greater desire to ‘follow in the footsteps’ of a relative who served. For me, when battlefield guiding, it is the part of the job that I love the most. Don’t get me wrong – I enjoy a general tour around the main tourist sites as well as the next person but it is in analysing the minutiae of war diary entries and working out such mundane things as billeting arrangements or where sports events were held that yields most fulfilment.

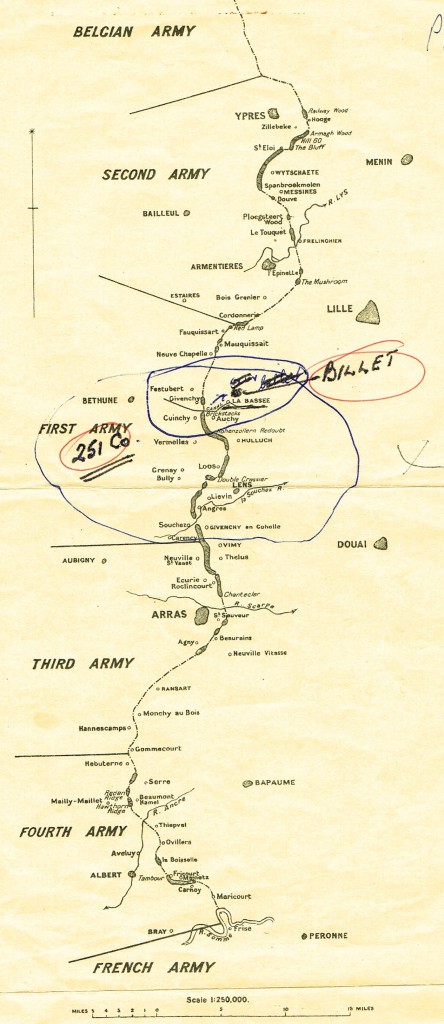

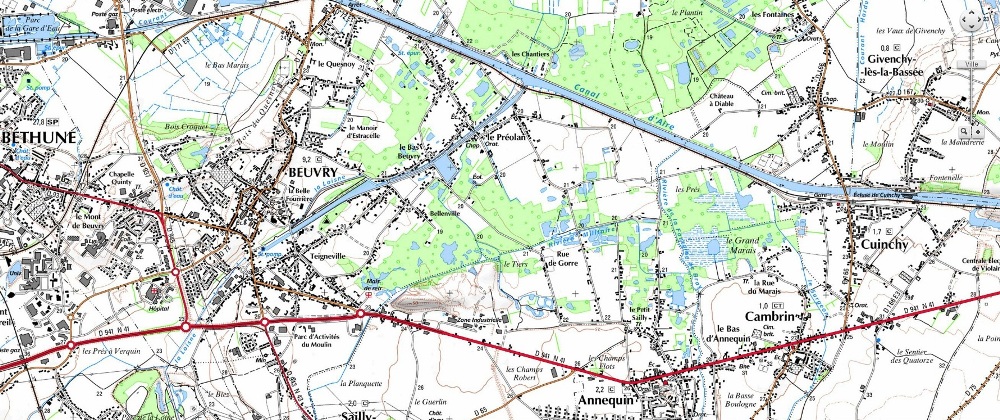

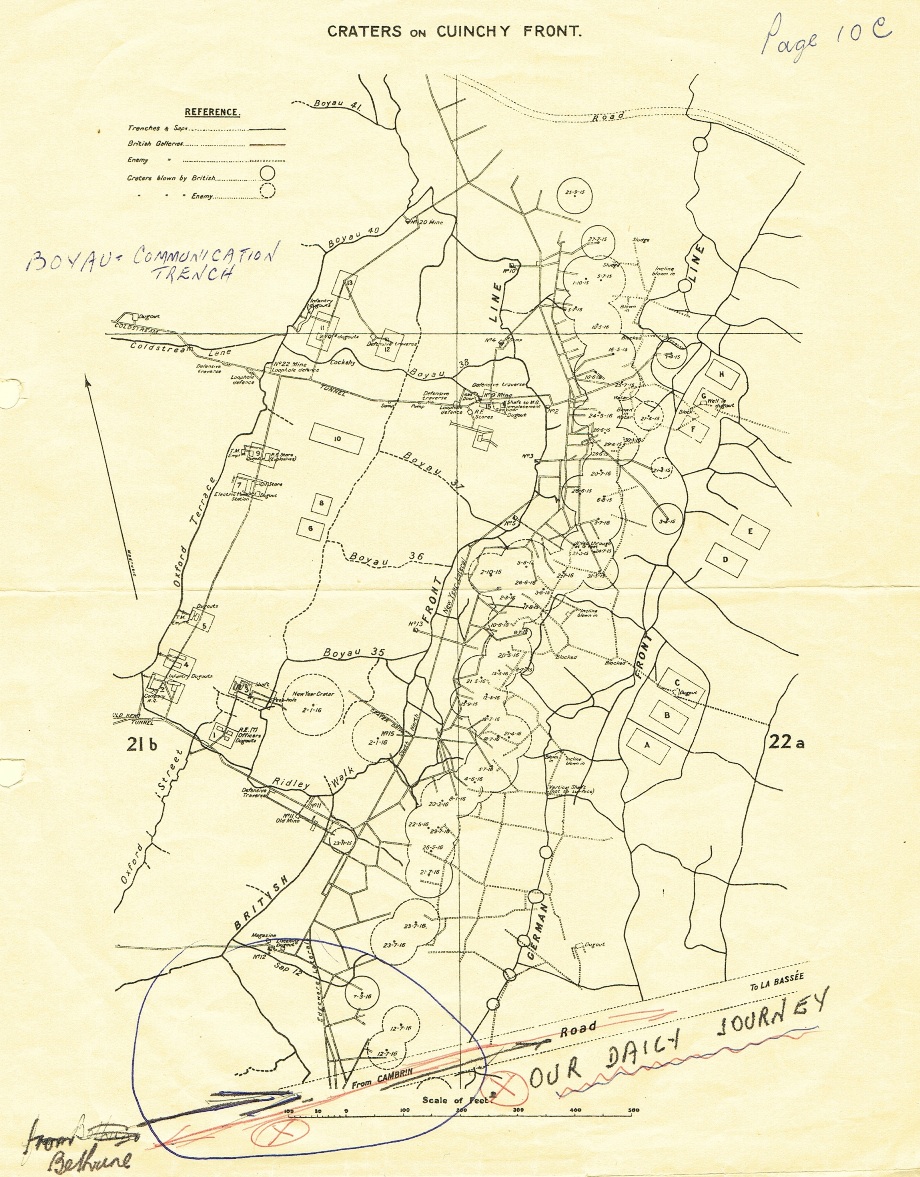

I recently returned from a bespoke trip following the 17th Middlesex Regiment (Footballers’ Battalion) around various villages and towns in French Flanders and the Gohelle coalfields in which they spent November 1915 – March 1916. My client’s grandfather had enlisted underage and spent four months with the battalion before being wounded in mid-March 1916; a wound which saved him from taking part in the Battalion’s action at Deville Wood on the Somme. During the four month period the Battalion held trenches at Cambrin, Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée and Festubert before taking over the Calonne sector from the French at the end of February.

Private James MacDonald, 17th Middlesex – first casualty of the battalion at Cambrin Churchyard Extension

Over the course of our three day trip we visited all of these places, as well as many not associated with the 17th Middlesex; Fromelles, Aubers, Hulluch and Loos. Our stops were not solely restricted to places but included visits to 17th Middlesex Regiment men who had been killed in action. To stand at the grave of Donald Stewart (who served under the alias of Private James MacDonald) in Cambrin Churchyard Extension and know he was the first man of the battalion to be killed in action struck a particular chord. However, for me the highlight came during our visit to Béthune. The Battalion war diary for 2 December records a move to Béthune and billeting in the College des Jeune Filles. I had an old postcard of the college and knew the greater part of it still stood so arranged to visit it during our lunch stop.

Battlefield guides will recognise the satisfying feeling – being able to tell someone that their relative was at that spot on a certain date, not nearby or somewhere in the town but here, actually here. We had the same feeling eating our lunch of ham and cheese baguettes in the square at nearby want to buy ambien online Beuvry. A poorly-attended market filled half of the square but, as we sat eating, I was able to explain that this village, now almost a suburb of Bethune was where the Footballers’ Battalion had spent Christmas Day 1915. There was no plaque commemorating this event, no visible link at all, just the knowledge that men of the Battalion would have walked around the square over the festive time, amongst them my client’s grandfather. It made the lunch, eaten in the car whilst a steady drizzle fell that bit more special.

After a tour around the Loos battlefield I took my client to the site of Middlesex and Football Trench in the Calonne North sub-sector. It was here in that his grandfather was wounded in March 1916. The war diary of the 16th records ‘4 casualties occurred from GRENADES, 2 in “B” Coy and 2 in “D” Coy’; it is likely that my client’s grandfather was one of those wounded men as he left France on the 18th, crossing the channel for treatment at a hospital in Britain. Such were the effect of the wounds received that he was discharged from service three months later. Compared to many who served, his war was unremarkable – his service record shows he played no part in any major offensive and yet the four months he spent with the 17th Middlesex from November 1915 – March 1916 had a profound effect on him for the rest of his life.

Map of Calonne North Sector showing Football and Middlesex Trenches . Reproduced from 6th Infantry Brigade War Diary held at National Archives, Ref: WO95/1353

Calonne North map overlaid on to Google Earth. Football Trench runs between the A21 motorway and the Lens – Bethune railway embankment.

Football Trench ran through what is now an open field next to the A21 motorway and the urban sprawl of miners’ cottages of Liévin. The railway line from Lens to Bethune runs across the northern tip of Middlesex Trench. Much of the rest of it is hidden under a civilian cemetery or is being built upon for new housing. A casual visitor to the site today would find it far from enchanting. Locals stared at our car with British number plates; clearly, the back streets of Liévin didn’t see too many battlefield tourists. However, the relative inaccessibility of the spot made visiting it that bit more special. To those of us in the car, it felt as though we had tracked down a site rather than merely followed the tourist signs. Having researched the young Middlesex soldier it certainly had an effect on me. It was a real pleasure to be able to share these places with his grandson; not just the obvious sites of front line and communication trenches but the places in he was billeted, the towns and villages he would have known well and the roads he marched along on his route to and from the front. To me, this is what makes following in a soldiers footsteps such an enriching experience.

N.B. A very readable account of the 17th Middlesex Regiment is Andrew Riddoch & John Kemp’s ‘When the Whistle Blows: The Story of the Footballers’ Battalion in the Great War’ – highly recommended.

Following in the footsteps of the 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade at the Battle of Arras (April – May 1917)

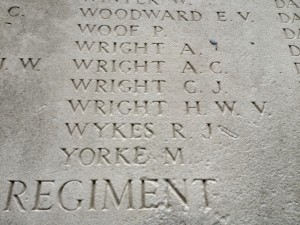

Earlier this month having spent a few days recceing sites and walks for upcoming trips I spent a day showing a client, Tony Wright, around the Arras battlefields following in the footsteps of his great uncle, S/30401 Rifleman Herbert William Victor Wright, 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade who was killed on 3 May 1917. It was most likely that Herbert had joined the battalion as one of nearly four hundred reinforcements received in January 1917. As such, the spring offensive at Arras would be his first major battle.

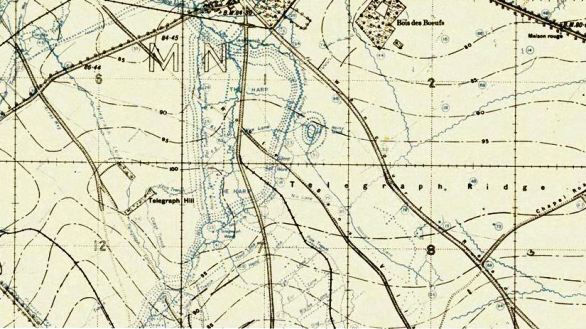

Sadly, Herbert Wright’s service record no longer existed and so we were unable to determine which company he had served in. However, with the knowledge that he would have been ‘in the area’ we started off by looking at the battalion’s role in the 9 April attack. The 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade was part of 42nd Infantry Brigade, 14th (Light) Division. The divisional objectives for 9 April were to capture the strong German position known as the Siegfried Stellung, (Hindenburg Line) which the Germans had fallen back to throughout the month of March. The hinge of the ‘old’ German line and new Hindenburg Line was the village of Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines. South of the village lay the 14th Division’s objective, the southern part of The Harp, a formidable position some 1000 yards long and 500 yards wide, full of tangled field defences. Along with Telegraph Hill to its immediate south its dominant position enabled German defenders to fire in enfilade northwards up Observation Ridge and southwards to Neuville Vitasse; its capture was absolutely critical.

Looking across the rising ground of The Harp. The 9th Rifle Brigade advanced across here on 9 April 1917

The role of the 9th Rifle Brigade on 9 April was limited to that of ‘moppers-up’. An initial assault was to be made against the southern portion of ‘The String’, a trench running down the length of The Harp, by the 5th Ox and Bucks Light Infantry and 9th King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Once captured the 5th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry would then pass through or ‘leapfrog’ the two battalions to capture the second objective close to the Blue Line running south from the rearward face of The Harp down the Hindenburg Line. Nearly seven hours after the initial advance and with these objectives taken B & D Companies of the 9th Rifle Brigade, under the command of Captain Buckley were to leave their positions in and around the old German front line to clear the ground between the Blue and Green lines within the Brigade boundaries.

They would also occupy an outpost line north east of the Tilloy – Wancourt road (now the D37). Considering the magnitude of the day’s fighting the Battalion war diary gives scant information about the work completed other than to record the final objective was gained by 1.30pm with one hundred prisoners and two machine guns captured. Casualties sustained were Captain D.E. Bradby killed , 2/Lt H.M. Smith wounded and fifteen Other Ranks wounded. Despite differing figures from those provided in Brigade records it is clear that losses amongst the 9th Rifle Brigade were extremely light when compared to other battalions within 42nd Brigade.

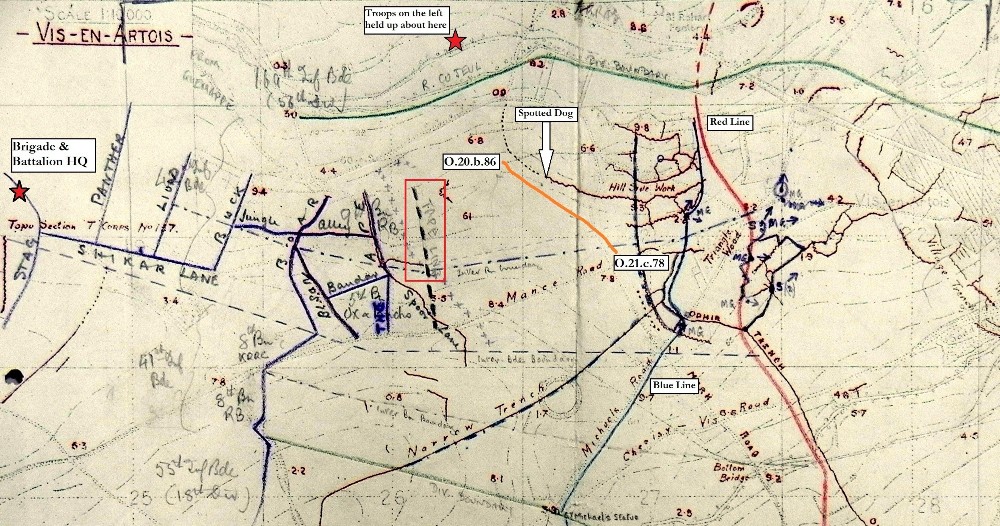

After relief on 12 April the Battalion spent time in training where they received a draft of fifty two reinforcements. On 23 April the Battalion began their march back to the battlefield, moving into newly captured positions between Guémappe and Chérisy on the evening of the 24th. The war diary records constant shellfire for this entire period; on one day alone 2/Lt J.M. Harper and a further sixteen Other Ranks were wounded. Between 30 April – 2 May the Battalion were in reserve but provided working parties to dig out a new communication trench named Jungle Alley running between the Ape and the Boar trenches before taking up their positions in the front line north of Chérisy on 2 May. The stage was set for a renewal of the offensive; three armies would be attacking along a fourteen mile frontage from Bullecourt in the south to Fresnoy in the north. Having suffered such comparatively small losses on 9 April the 9th Rifle Brigade was to take a leading part in the coming battle, attacking on the left of the Brigade next to the 5th Ox & Bucks Light Infantry. The 5th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry and 9th King’s Royal Rifle Corps were in Brigade Reserve.

The decision to launch the attack at 3.45am in darkness was contentious. Many commanders protested to no avail. A further complication for the 9th Rifle Brigade was their position nearer to the enemy than neighbouring units. As such, they were not to advance from their jumping off line until eighteen minutes after Zero Hour. The Battalion had two objectives; firstly to capture the Blue Line running in front of Triangle Wood and through Hill Side Work and then to push on to the Red Line, completing the capture of both positions. Advancing from a line 150-200 yards east of the front line marked by white tape fixed to the ground, the Battalion was to advance behind a ‘creeping barrage’ of artillery shells exploding in a slowly moving curtain across the battlefield.

Ten minutes before Zero Hour the first wave left the assembly trenches to line up on the tape. At 4.03pm they advanced, followed by the second wave that left the assembly trenches at Zero +42 minutes. In common with many units who attacked that dreadful day, no further report was ever received from the companies in the first wave. German artillery fire was extraordinarily heavy (lasting for over fifteen hours) with eight company runners either killed or wounded. Post -action reports noted the first wave veered to the right in the darkness, striking a new German trench wired and held by the enemy. Despite this, it was captured by Zero + 40 minutes and advance progressed. However, enfilade machine gun fire caused heavy casualties and ‘few, if any ever reached the rear of Hill Side Work’. All eight officers of the first wave became casualties very early in the day, some being wounded several times. Only seven NCOs of the first wave ever returned. The second wave fared no better. As their advance was in daylight they were subjected to machine gun fire sooner than the first wave and also came up against machine gun positions which had been established after or missed in the dark by the first wave, in addition to enfilade fire from across the Cojeul valley near St Rohart’s Factory.

Cross left in memory of Herbert Wright, 9th Rifle Brigade. Triangle Wood and Hill Side Work are on the horizon

The second wave was finally held up just in front of Spotted Dog Trench which was held by the enemy; they dug in along a line of shell holes about 600 to 700 yards in front of their original front line at Ape Trench. A German counter-attack against the 18th Division who had captured Chérisy forced their line back to its starting position; this action rippled northward with orders sent out to recall the Battalion. Such was the dominance of German artillery and machine gun fire (firing continuously from both flanks and from across the river valley) that these orders could only be communicated to two platoons; it being impossible to contact the remnants of the battalion occupying shell holes close to Spotted Dog Trench. On the evening of the 3rd two patrols were sent to recall one company holding a line of shell holes and strong point close to the German trench. Over the next couple of nights survivors of the 9th Rifle Brigade’s attack returned to the original British line. The Battalion’s casualties during the day’s operations were 12 officers and 257 Other Ranks. The 9th Rifle Brigade was relieved on 4 May before heading back to The Harp. This disastrous day marked the beginning of the end of the Battle of Arras. Desperate fighting continued for possession of Roeux, its infamous Chemical Works and Greenland Hill plus around Fresnoy which was recaptured on 8 May. However, by then British attentions were turning northwards to Flanders.

As Herbert Wright’s company is unknown it proved impossible to know whether he formed part of the first or second wave of attackers. Tony and I we walked the attack, passing the assembly trench positions, taped line from which the battalion advanced before moving to the final positions reached. It was here that Tony laid a small poppy cross in memory of his great uncle. Herbert Wright was one of ninety seven men of the Battalion killed on 3 May; all but two are commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the Missing. We visited the Arras Memorial and saw Herbert Wright’s name on Panel 9.

His remains may be buried in the grave of an unknown soldier or still be out on the battlefield. The Third Battle of the Scarpe, as the fighting over 3/4 May was named, was an unmitigated disaster for the British Army which suffered nearly 6,000 men killed for little material gain.

In the Official History, Military Operations France and Belgium 1917 Cyril Falls gives the following reasons for the failure on 3 May 1917 in the VII Corps frontage:

“The confusion caused by the darkness; the speed with which the German artillery opened fire; the manner in which it concentrated upon the British infantry, almost neglecting the artillery; the intensity of its fire, the heaviest that many an experienced soldier had ever witnessed, seemingly unchecked by British counter-battery fire and lasting almost without slackening for fifteen hours; the readiness with which the German infantry yielded to the first assault and the energy of its counter-attack; and, it must be added, the bewilderment of the British infantry on finding itself in the open and its inability to withstand any resolute counter-attack.”

This stark paragraph illustrates perfectly the battlefield during the 3 May 1917 fighting; nightmarish, terrifying and bloody. Having been at home for a week now I am still thinking about it and the windswept ridge between Guémappe and Vis-en-Artois.

“I spent an extraordinary day with Jeremy walking in the footsteps of my Great Uncle, who fell on May 3rd 1917 at the Battle of Arras. He did a wonderful job of balancing a very good explanation of the complexities of the overall battle itself with a highly emotional and personal end to the day of literally experiencing his final hours. As my Great Uncle was a private soldier, without detailed records of his service easily available, I was deeply impressed by how he brought together a range of different sources to nevertheless give me a really specific and personal understanding of what he and his comrades went through. It was an absolutely unforgettable experience”. Tony Wright

A good write up of the part played by one young officer, 2/Lt William Clarke Wheatley, former pupil at Sandbach School who was killed in the 3rd May attack can be found on Conor Reeves’ excellent website: http://sommejr.wordpress.com/william-clark-wheatley-3517/.