Archive for the ‘Research’ Category

A raid with severe repercussions: the mutilation of 8th Lincolns dead at Ghissignies, 2-3 November 1918

In the course of research for a client whose relative had served in the 13th Battalion Royal Fusiliers I was reading the unit war diary when the following passage, taken from 11 November 1918, the day the armistice came into effect, stopped me in my tracks:

11 November 1918

Bodies of dead killed on 24/10/18 were buried at GHISSIGNIES. It was found that the majority of the men had been deliberately shot in the head by the enemy. The men in question had been wounded: those that were able to walk were taken by the enemy and the remainder dealt with as stated above. Bodies of men of the Lincolnshire Regt. who had been killed about 30th Oct. were found to have been mutilated, hands hacked off at the wrists and eyes gorged [sic] out.

[13th Battalion Royal Fusiliers War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2538/3]

I have read plenty of British atrocities against German troops on the Somme in 1916 (there are files of such accounts in the archives at Freiburg). But on the British side I was only aware of Major Henry Hance’s (179 Tunnelling Company RE) description of Mash Valley on the Somme in mid-July 1916 in which he describes the British dead having been bayoneted ‘always thro’ the neck’ and the dead hanging on the wire having head their heads bashed in. But the 13th Royal Fusiliers war diary extract invited more research. Could this really have happened – British soldiers with hands hacked off and eyes gouged out by the enemy?

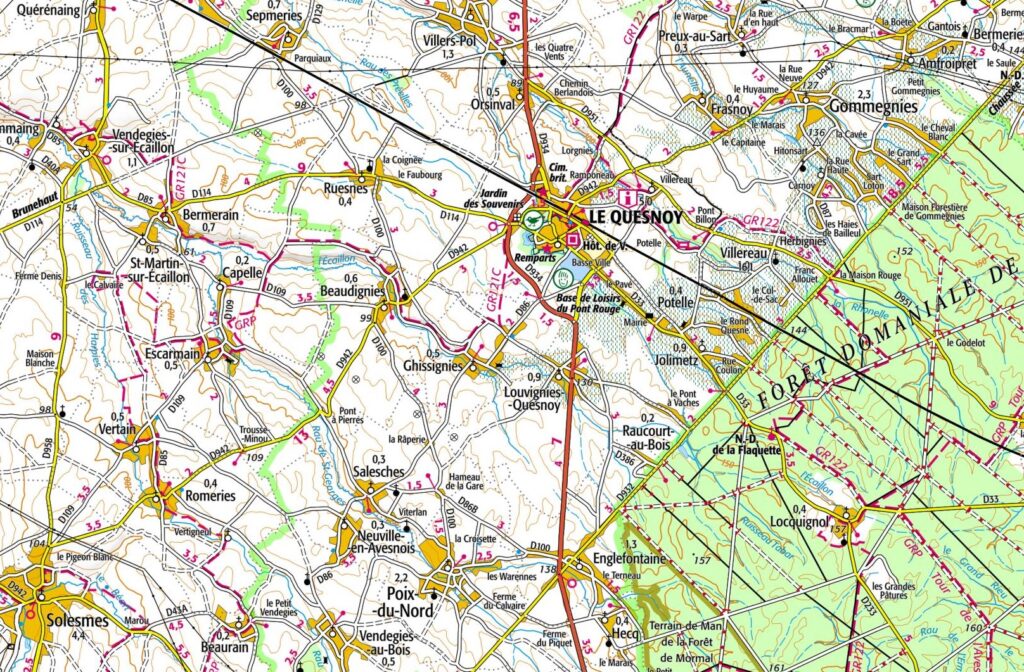

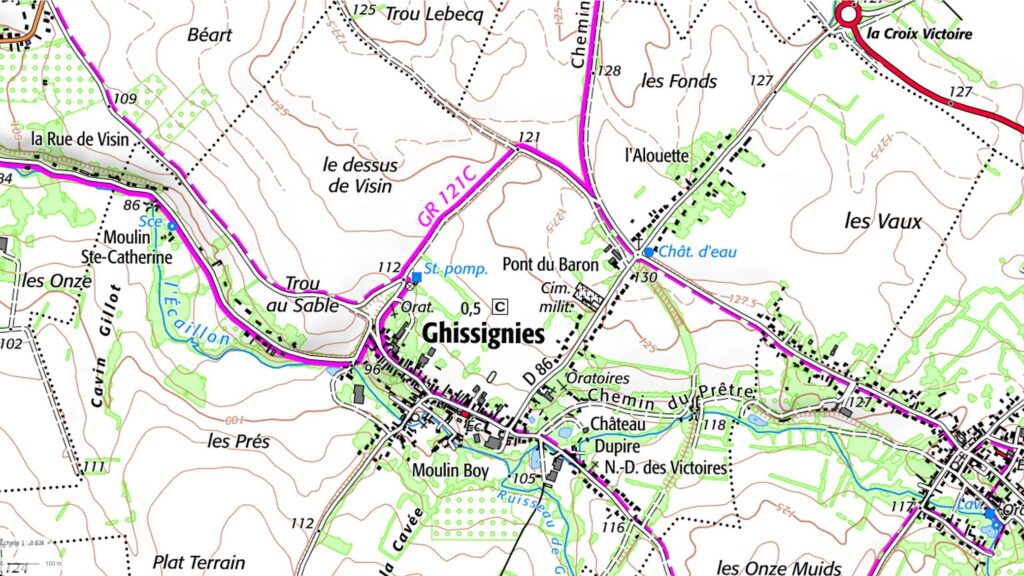

No additional information was available in the 13th Royal Fusiliers diary so moved on to the 8th Lincolnshire Regiment’s diary. The 13th Royal Fusiliers’ account had mentioned the battalion’s dead ‘who had been killed about 30th Oct.’ A brief look at the 8th Lincolns’ war diary confirmed any dead could not have been from that date (the battalion were in the line under heavy shellfire and had two Other Ranks wounded). Much more likely was the night of 2-3 November when ‘A’ Company raided German posts at the northern end of the village of Ghissignies, southwest of Le Quesnoy (of New Zealand Division fame).

IGN map showing Ghissgnies in relation to Le Quesnoy

A Google Maps link to the village of Ghissignies can be found by clicking HERE.

The relatively sparse diary entries for 2-3 November are recorded below:

2/11/18 In the line – “A” Coy raided posts at level crossing in X5a at 23.45 hrs. Between 30 & 40 casualties inflicted on enemy. Heavy resistance offered. Casualties 11 O.R. killed, 18 O.R. wounded, 1 O.R. missing, 1 O.R. acc[identally] wounded.

3/11/18 In the line – Trench mortar activity on front line – casualties 12 O.R. killed, 17 O.R. wounded, 1 O.R. missing, 1 wounded acc. sprained wrist.

[8th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2529/1]

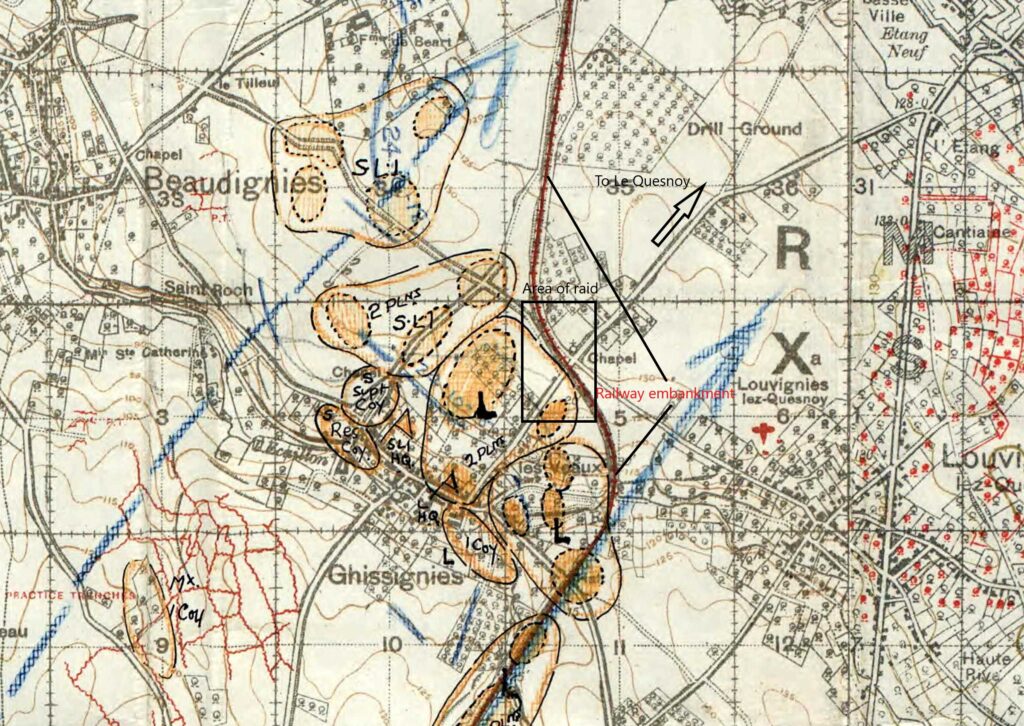

Annotated map extract from 37th Division HQ war diary showing Ghissignies and the chapel crossroads with area of raid marked

Clearly, the success of a single company raid which resulted in 31 casualties to the attacking force is questionable. The following day the Battalion cleared the position raided on 2 November with relatively little loss. Their casualties that day were the last sustained by the Battalion in the Great War.

4/11/18 “D” Company withdrew 2 platoons to SALECHES in X.19.b – 2 platoons followed left flank 111th Infantry Brigade mopping up the crossing & orchards in vicinity of chapel in X.5.a & b and R.35.. c & d. – 1 platoon establishing posts X.5.b.30.85 to R.35.d.15.15 –1 platoon X.b.20 – 70 to X.5.b.10.90. 24 prisoners captured in this operation – working from the south, 2 platoons of B. Coy mopped up Railway to Level Crossing in X.5.a.

In the evening the Bn moved to LOUVIGNY in area S.8.b & d.

[8th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2529/1]

As is so common when studying trench raids, the area in which this action took place is very small. British wartime maps (above) show the Le Quesnoy road leading to a crossroads at the north-eastern edge of the village. A chapel is marked on the crossroads but online research shows this to have been the existing calvary which was unveiled in 1852.

The Calvaire at the crossroads, Ghissignies. Image from: http://villesetvillagesdelavesnois.org/ghissignies/ghissignies.html

As part of 63rd Infantry Brigade, I hoped that the 8th Lincolns’ raid of 2-3 November would receive more attention in the Brigade war diary. And it was here that I struck gold with a detailed account provided in a Report on Operations, Oct 23rd – Nov, 4th, 1918, including gruesome descriptions of disfigurement and mutilation of British dead:

Nov 2nd.

At 2345 hours 8th Lincolnshire Regt. raided the enemy’s positions on the railway about the Chapel, X.5.a., under an artillery and trench mortar bombardment. This raid was carried out on a one platoon front with one platoon in close support. The railway was entered by the leading platoon and several casualties were inflicted on the enemy. 3 prisoners were taken but subsequently escaped. The supporting platoon was unable to reach the railway owing to heavy hostile machine-gun fire from the railway cutting. Our casualties were somewhat heavy, including 12 other ranks reported missing. In the subsequent advance on the 4th inst., the bodies of 11 were found buried by the enemy in the railway cutting. On being examined the bodies were found to have been terribly disfigured. One, the body of No. 241186 Corpl. G.A. DICKENSON, had six bayonet wounds, and one hand cut off. In addition both eyes were missing and had apparently been gouged out. It is not thought possible that these wounds could have been inflicted in the course of actual fighting.

[63rd Infantry Brigade War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2529]

A railway embankment bisected the Le Quesnoy road just before the crossroads. However, as noted in 63rd Brigade diary, British maps of the area were not wholly accurate:

The maps of this area had been found to be very misleading: what was taken to be a level crossing at X.5.a.5.5 was proved to be a very steep railway cutting fully 12 feet deep with a destroyed road bridge over the railway.

So, for the two assaulting platoons, what had appeared to be a standard raid had swiftly deteriorated into a tragic and bloody action. The war diary for 37th Division General Staff HQ reiterates the salient points of the raid:

Successful raid carried out by 63rd Brigade at 23.45 hours. Objective of raid level crossing X.5.a. Raiding party reached objective and inflicted severe casualties on the enemy. 3 prisoners were taken but owing to the escort being wounded on their way down with prisoners they escaped.

[37th Division Headquarters Branches and Services: General Staff War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2515]

However, it was 37th Division Intelligence Summary No 8., dated 7 November 1918 that provided most detail. It showed that the attacking force was met by sustained machine gun fire as soon as the advance began. One party working north along the railway made it into the 12ft deep railway cutting which was full of cubby holes, both at the bottom and higher up. Heavy fighting ensued and the report concluded thirty casualties were sustained by the Germans (almost certainly an overestimate – there are countless examples of British estimates of German casualties in raids bearing no relation to actual losses recorded in German reports. These numbers should always be treated with a healthy dose of scepticism – after all, those making the claim knew all too well there was no way their superiors could check inflated claims). Having suffered heavy casualties themselves and low on bombs and ammunition, the party withdrew. Other parties aiming to work south along the railway were stymied by sustained machine gun fire which caused heavy losses amongst the attacking Lincolns.

There is also mention of three German prisoners shooting their lone escort and escaping and a warning that prisoners should be properly searched for weapons upon capture to prevent such instances occurring.

7/11/18.

A raid was carried out on the night 2/3rd of November by two platoons of the right Bn in the vicinity of the level crossing in X.5.a. at 23.45 hours. The assembly was successful, but two machine guns, one on the railway crossing and the other about 30 yards north of the house X.5.a.40.35 opened fire immediately the party started to advance. One party, working north along the railway reached the hedge in spite of heavy fire, crossed it, and dropped into the railway cutting which was found to be full of cubby holes, both at the bottom and higher up.

The party started to mop up at once but was unable to reach the machine-gun at the level crossing. 30 casualties were inflicted on the enemy in spite of considerable opposition, particularly from the men in the upper cubby holes.

The party was finally forced to withdraw, their bombs and ammunition being exhausted and only one officer and 2 O.R. remaining unwounded.

Three prisoners was sent back under a lightly wounded escort. One of those prisoners drew a revolver and shot his escort. The escort of the other two was again wounded whilst withdrawing and they also escaped.

Other parties attempting to mop up posts in X.5.a.5.4 and to work south along the railway were unable to gain ground owing to heavy machine-gun fire in spite of repeated efforts to knock out the guns. The majority of our men were wounded in this attempt.

The raid was successful in that it showed that the enemy was still holding this section of the front in strength.

NOTE. The loss of the three prisoners emphasises the fact that prisoners should be thoroughly searched for weapons directly they are captured.

[37th Division Headquarters Branches and Services: General Staff War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2515]

Based upon these accounts it seems most likely the soldiers recorded in 63rd Brigade war diary whose ‘bodies were found to have been terribly disfigured’ probably came from the party which entered the railway embankment and fought so bitterly with the enemy ensconced in their cubby holes. Sadly, I doubt it will be possible to find further information on the events of that night – whether or not the wounds to British soldiers were deliberate but experience leads me to believe they were. The troops had seen their fair share of fighting and killing and knew the difference between wounds sustained in the course of action and deliberate mutilation. That these accounts are taken from official British sources (war diaries from Battalion, Brigade and Division) as opposed to a post-war memoir also adds credence to their veracity. Furthermore, by this stage of the war there was no need for inflated accounts of German atrocities to be used for propaganda.

It is certainly possible that assaulting Lincolns who entered into a bloody fight in the railway embankment, killing a number of German defenders were offered no mercy. Maybe German survivors were not in the mood to take prisoners and wanted revenge? To assume such incidents did not happen over four years of a bitter war is naïve and misses the essential point of warfare – namely, to kill the enemy.

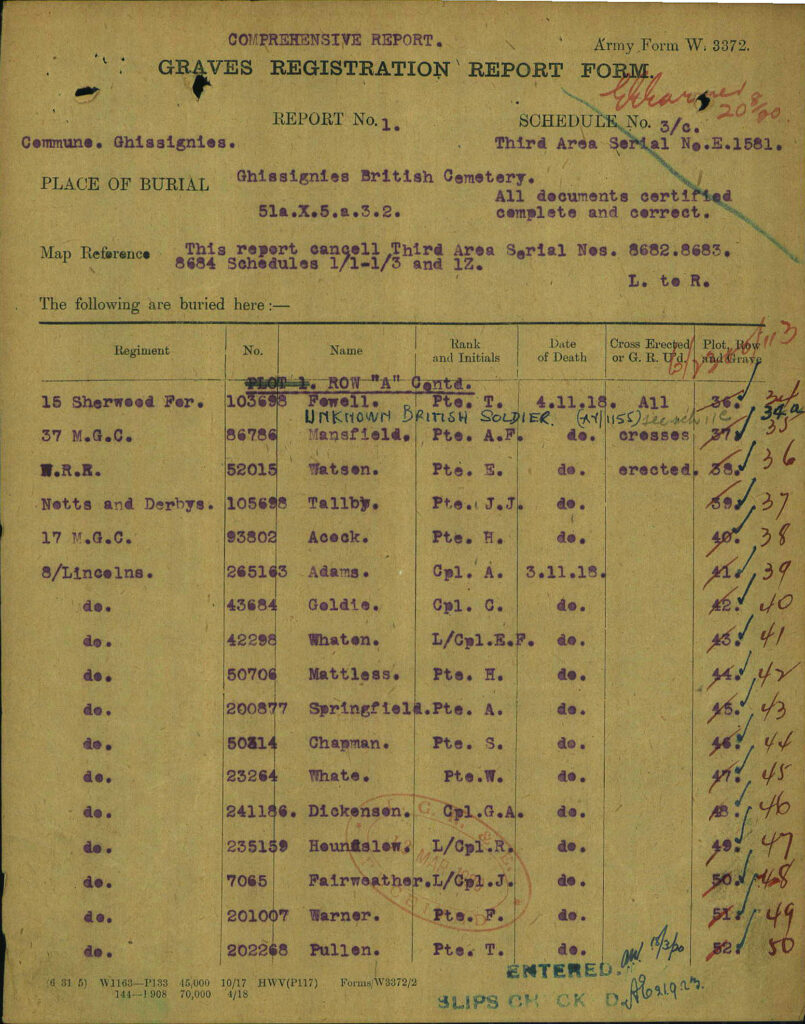

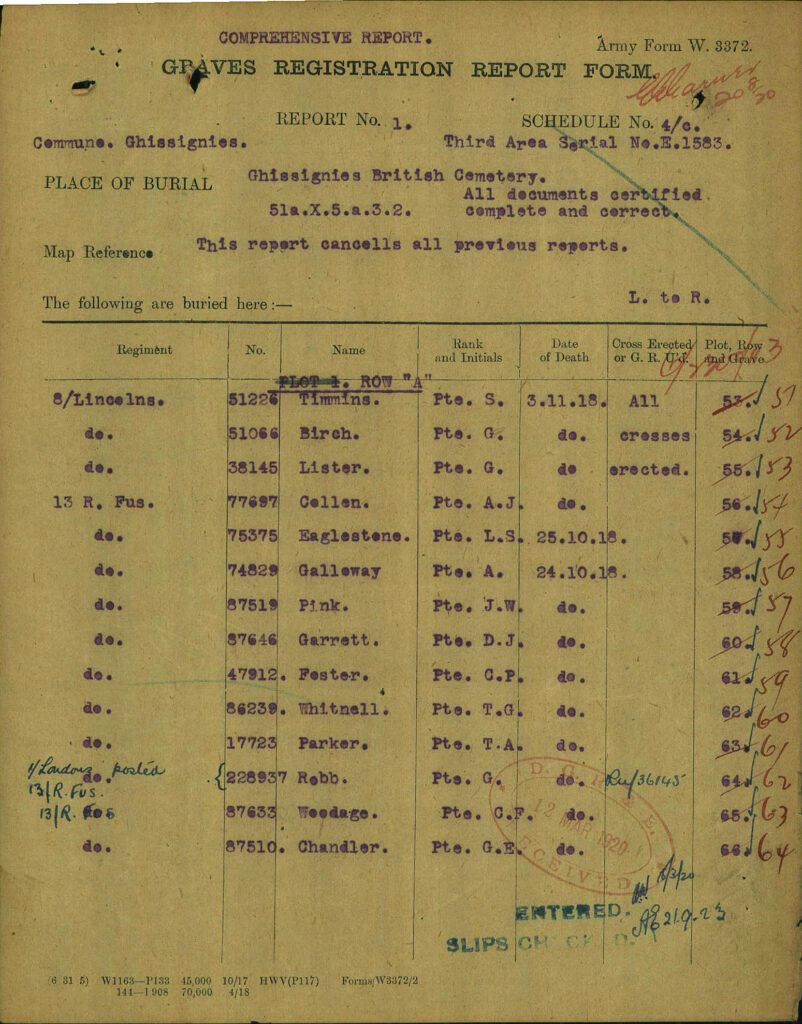

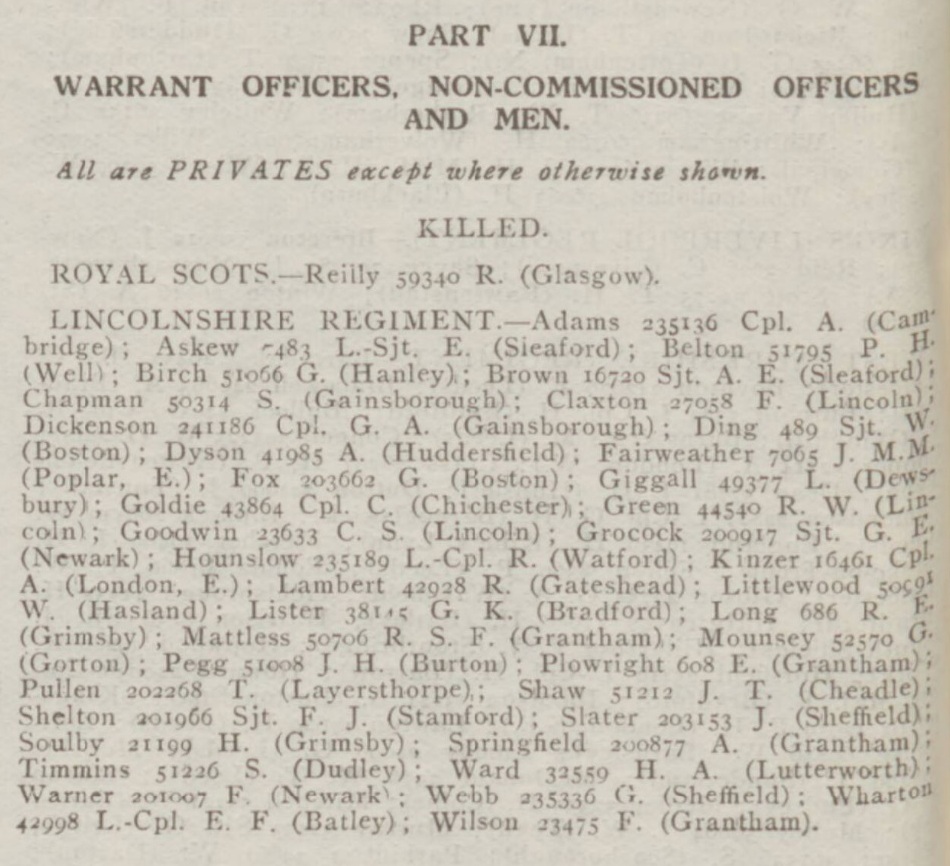

As for the 8th Lincolns dead, there are sixteen soldiers from the Battalion now buried in a long line in the nearby Ghissignies British Cemetery. Based upon the sources above, eleven of these were disinterred from their shallow burial in the railway embankment – these are the men whose bodies were disfigured – with the remaining five ‘conventional’ casualties from the action (most likely from machine gun fire as they attempted to work south along the railway).

Below is a list of these dead taken from the CWGC website.

It includes 241186 Corporal George Dickenson whose body had six bayonet wounds, one hand cut off and both eyes missing (apparently gouged out). Two graves along lies 7065 Lance Corporal John Fairweather MM, a recipient of the 1914 Star who went overseas with the 1st Battalion in September 1914, served with a number of different battalions and earned the Military Medal in 1917. I would welcome any further detail on these men. Many of the dead from this raid are listed in the Weekly Casualty List (War Office & Air Ministry ) for 28 January 1919.

Weekly Casualty List (War Office & Air Ministry ) – Tuesday 28 January 1919

So, a strange and disturbing case of battlefield mutilation right at the end of the war. The village is once more a quiet spot and a roundabout now sits at the road junction. A water tower has been built between the Route de le Quesnoy and Route de Louvigny. Other than the military cemetery 100 metres down the road towards the village centre there is nothing to indicate any fighting took place here. When we get out of lockdown and visits to France and Flanders recommence I will stop at Ghissignies, far from the well-trodden spots of the Ypres Salient or the 1916 Somme battlefield and pay my respects to those men killed just a few days before the guns fell silent.

Modern aerial view of raid site at Ghissignies. Taken from Geoportail

IGN map of the village of Ghissignies

Image from Google Street View looking up to site of railway embankment and raid

13 Sept 1949 aerial of Ghissignies, the railway embankment and crossroads

15 November 1968 aerial of Ghissignies showing water tower to the east of the crossroads

JB, 31 March 2021

Filming with David Walliams for Who Do You Think You Are? and a look into his great-grandfather’s wartime service

Back in early March just before lockdown I spent a half day filming with David Walliams at the Guards’ Chapel for the new series of Who Do You Think You Are? David’s episode was broadcast tonight, 19 October, on BBC One. I was asked to set the scene for David’s great grandfather, John Boorman, who served in the Grenadier Guards.

With David Walliams at the Guard’s Chapel filming Who Do You Think You Are?

His was a fascinating but ultimately tragic story. Having enlisted at the end of September 1914 it is possible that his above average build (he weighed 140 pounds and had an expanded chest of 36 inches) alongside his height of 5 feet 9 inches meant he was guided in the direction of the Guards by recruiters.

Having undergone training John proceeded overseas. His Medal Index Card and surviving service record confirm his date of arrival in France as 16 March 1915. John joined the 1st Battalion and while the service record does not say when he joined them, the battalion’s war diary notes the arrival of a draft of six officers and 350 men on 20 March 1915. It is assumed John was in this draft.

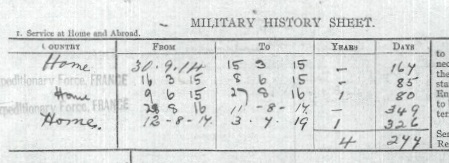

Extract from John Boorman’s service record showing time spent in the UK and overseas

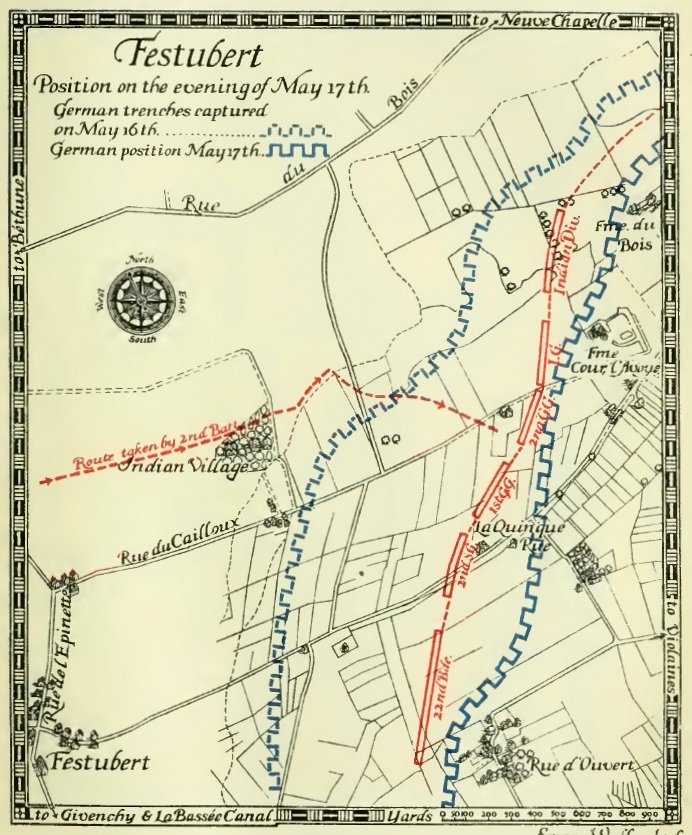

Two months of trench routine and a few weeks break in divisional reserve during which the battalion practice drill and route marching precede John’s first battle, the Battle of Festubert. In comparison to the titanic battles of 1916 & 1917 this affair, in the flat lands of French Flanders, was small but no less bloody. To soften up German positions over 100,000 shells had been fired before the assault. Early in the morning of 16 May the 1st Grenadier Guards followed behind the 2nd Border Regiment, passing through them to attack German trenches. There was no great distance gained and it certainly didn’t alter the course of the war but this action was John’s first taste of the harsh brutality of war. Battalion reports describe close quarter fighting, killing the enemy, taking prisoners plus clearing trenches by throwing bombs. It was a tough baptism of fire, as recorded in Ponsonby’s Volume 1 of The Grenadier Guards in the Great War of 1914-1918:

The 1st Battalion Grenadiers came in for a great deal of shelling, and one shell burst in the middle of No. 8 Platoon, killing four men and wounding many others, including Lieutenant Dickinson and Lieutenant St. Aubyn, who was struck in the face by a piece of shrapnel. All the time a stream of wounded from the front trenches was passing by, some walking and some on stretchers.

Another entry in the Guards’ history records:

Rain began to fall at 6 p.m., and grew into a steady downpour. In the newly won trenches the men were soaked to the skin, and spent a miserable night. Everywhere the wounded, both British and Germans, lay about groaning.

For someone with only two months service in France those images must have made an impression. During the action at Festubert the 1st Battalion lost 2 officers killed, 2 officers wounded and 113 Other Ranks killed, wounded and missing.

Guards at the Battle of Festubert, May 1915

John was invalided back home for fifteen months, suffering from shell shock and returned to France on 28 August 1916. What is unclear is exactly when he rejoined the battalion as September 1916 sees many drafts arrive – 90 Other Ranks on 15th, 60 on 17th, 35 on 19th, 20 on 22nd, 23 on 27th and 72 on the 30th.

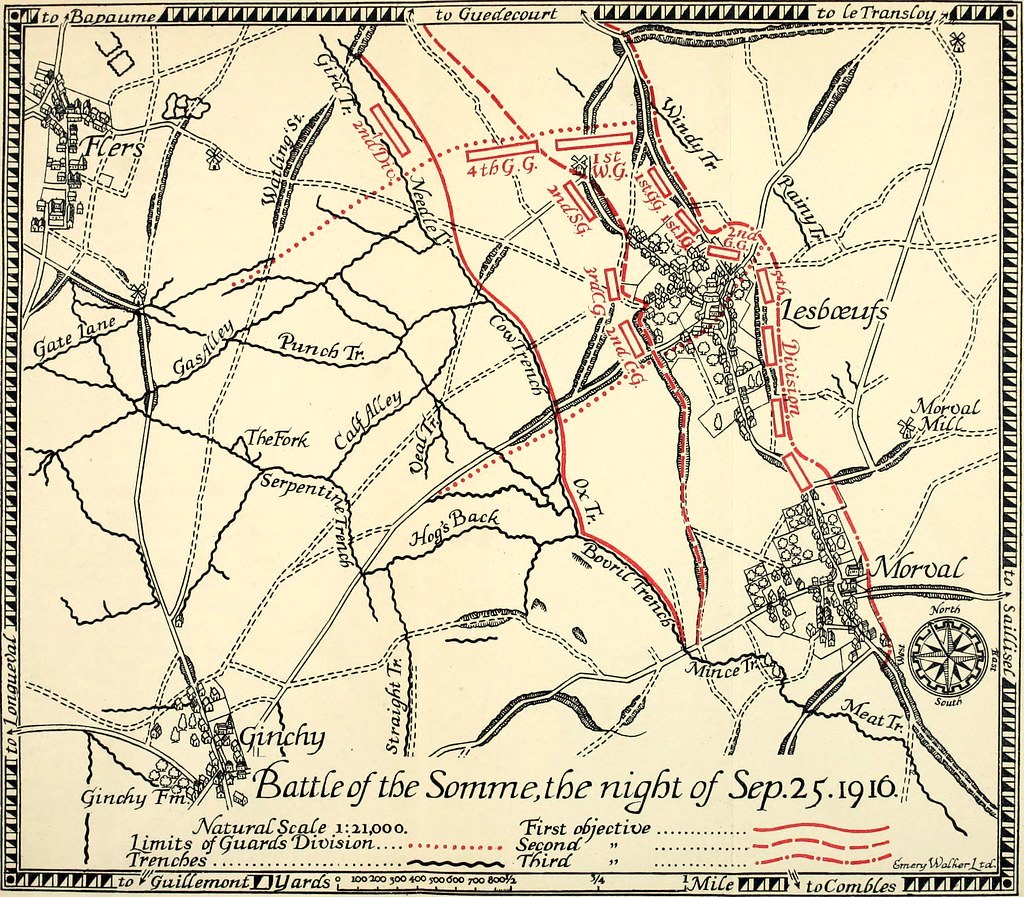

Those fresh men were much needed as the battalion was heavily involved in the Battle of the Somme that month. The attack towards the village of Lesboeufs was a costly affair for the Grenadier Guards, now part of the Guards Division. They had been in action on the 15/16th September but it was on the 25th that they took a major part. A few days prior to this the battalion was employed digging assembly trenches from which they would attack. The assault of the 25th was a success with the 1st Battalion passing through other Guards units to take their objective. The war diary has the wonderful line ‘Huns thoroughly demoralised’. Demoralised they may have been, but John’s battalion had paid the price for their success. In 11 days of action from 15-26 September they sustained a staggering 611 casualties.

Guards Division on 25 Sept 1916 at the Battle of the Somme

The month of October was spent way out of the line, absorbing new reinforcements and training before moving back to ground west of Lesboeufs in mid-November. By this time the Battle of the Somme was coming to an end. At least the men would no longer have to leave their trenches to assault enemy positions. But that did not mean an end to casualties – enemy shellfire saw to that. Holding exposed shellhole positions joined up to make short sections of trenches, John’s battalion endured mud and tough conditions that the battle had created. Even getting to frontline positions meant miles of trudging along muddy paths and duckboard tracks. Safety, warmth and aid would have seemed a long way away.

Having contended with autumnal mud it was a horribly cold winter with temperatures falling to minus 20 Celsius for a six week period. One blessing of this plummet in temperatures was the mud froze, but so did water…and men. The main enemy at this point was the weather, not the Germans. In mid-March John was admitted to No.34 CCS for treatment of lumbago and “ICT feet”. Having endured such terrible trench conditions many men suffered problems with their feet. It is likely that John moved to a hospital in Rouen, thereby missing his battalion’s part in pursuing the Germans in their retreat to the Hindenburg Line. At some point he rejoined his battalion and moved northward to the Belgian city of Ypres. This was for the start of the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) during which the Guards Division attacked on the opening day, 31 July 1917.

And for the filming with David, this was as far as I got! I was asked to set the scene for John’s war up to this point. David went over to Ypres and was shown where his great grandfather was wounded. The records show John Boorman arrived back in the UK on 11 August 1917 having been wounded in the left leg below the knee. Despite escaping the horrors of the battlefield John’s war continued. In April 1918 he was admitted to hospital and found to be suffering from mental instability (delusional insanity). A few months after he was transferred to the County of Middlesex War Hospital which contained a specialist military mental hospital. Sadly, it appears John never recovered from the mental scars of service on the Western Front and died, still in care, in 1962. His is a tragic story that reminds us of the enduring effect that war had on many men. While some seemed to return to civvie life and get on with things, return to work, raise a family and function normally, other men were unable to do so and suffered mental anguish for the rest of their lives.

My thanks to the estimable Chris Baker of https://www.fourteeneighteen.co.uk/ who did so much of the research into John Boorman’s story and provided me with a copy of the report he had prepared for Wall to Wall.

JB

‘Remembering Reading’s Heroes’ – a talk at Haslams Estate Agents for Reading FC and ABF The Soldiers’ Charity

Last week I gave a talk on behalf of Haslams Estate Agents and Reading Football Club in Haslams’ flagship office in Friar Street, Reading. The talk was part of a fundraising evening for ABF The Soldiers’ Charity and was attended by over 80 people.

The evening started with drinks and canapés (based on wartime fare which included such things as spam fritters and Maconochie’s steak pies) before 25 minutes from me discussing Reading in the Great War.

Canapés were based on a wartime theme

Most of the audience had little knowledge of this period of history and I was able to explain some of the more interesting stories I had found in my research. These included the story of Max Seeberg, a former Reading FC player from the 1912–13 season who, by the time was declared in August 1914, had retired and was working as a publican. Despite being a well-known and liked member of Reading’s community his German ancestry ensured he was locked up for the duration of the war. Remarkably, he seemed to bear no malice to Britain, becoming a naturalised British subject in 1920.

Talking about Max Seeburg, a former Reading FC player who was locked up for the duration of the war due to his German nationality

I also spoke about Ronnie Poulton Palmer, the England rugby player, Trooper Fred Potts VC and the tragic case of the Sutton family (of Sutton Seeds) whose five boys went off to war. By the end of March 1918 four of them had been killed, leaving Leonard Sutton (a wartime mayor of Reading) with his sole remaining son, Noel who survived the conflict despite being torpedoed mid-channel by a German U-Boat.

After a break for more drinks and canapés an auction and raffle was held. A weekend on the battlefield with me was auctioned off by local resident, Chris Tarrant. Over £3,000 was raised for ABF The Soldiers’ Charity.

Chris Tarrant auctions a weekend on the battlefield with me to raise funds for ABF The Soldiers’ Charity

An extract from the Reading Mercury of 12 August 1916 listing players associated with Reading Football Club serving in the forces

The second half of my talk focused on telling the story of a number of Reading FC players and their wartime service. Nine former players died in the conflict whilst others such as Joe ‘Bubbles’ Bailey achieved remarkable success as a fighting officer. In Joe’s case this resulted in the award of the DSO and three Military Crosses, all in a period of just seven months in 1918!

Speaking about Joe Dickenson, ‘the Footballing Grenadier’ who served in the 2nd Grenadier Guards and was killed at the Battle of Festubert in May 1915

My thanks to BBC Radio Berkshire’s Graham McKechnie, military historian Jon Cooksey and Reading FC historian Alan Sedunary who conducted a great deal of research on these players back in 2014.

The entire evening was a great success and I look forward to working with Haslams and Reading FC again in the future.

A selection of images from the evening (courtesy of Ben Hoskins http://www.bhoskins.com/) are shown below.

With Steve Woodford of Haslams, Brigadier Peter Walker of ABF The Soldiers Charity and serving soldiers

Pre-talk drinks and canapés

The audience seemed to enjoy the talk

More audience shots

Second Lieutenant Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. Image courtesy Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Ref GLRRM:04750.6

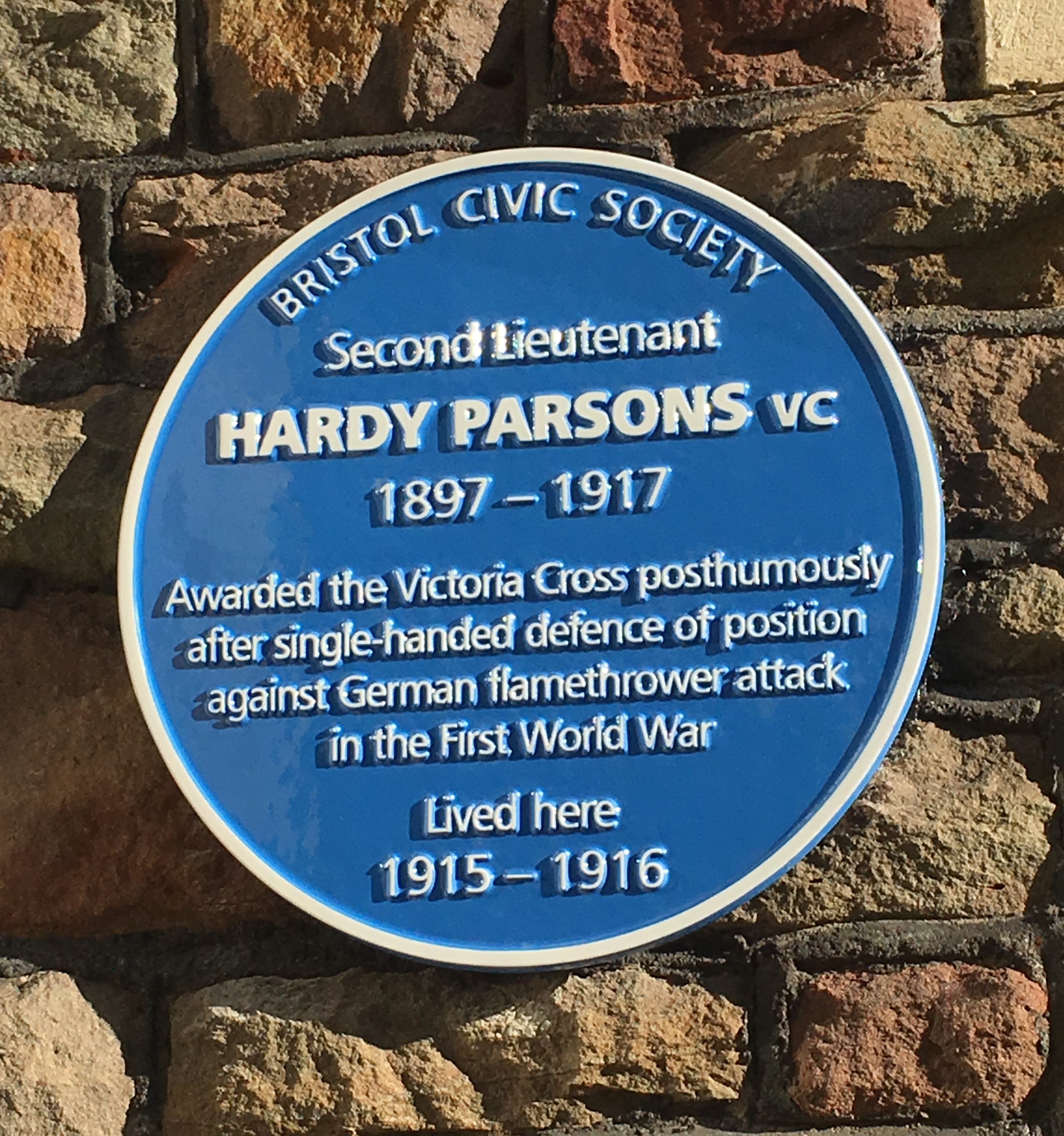

Today saw the unveiling of a Bristol Civic Society blue plaque at the former Bristol home of my local Victoria Cross recipient, 2/Lt Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. He lived a fifteen minute walk from my house and I have known his story for the past fourteen years that I have lived in the city.

My colleague Clive Burlton and I were determined to see Hardy’s strong association with Bristol and the West Country recognised. As his Government funded VC commemorative stone was unveiled in Rishton, Lancashire back in August we have spent the last year working on honouring Hardy’s local connections with a Bristol Civic Society blue plaque.

The plaque was unveiled by the Archie Smith and Grace Tyrrell, Head Boy and Head Girl of Kingswood School along with the Lord Mayor of Bristol, Cllr Lesley Alexander. The ceremony was attended by members of the Bristol Civic Society; the former Gloucestershire Regiment; the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum; the Bristol University Officer Training Corps; Kingswood School, Bath, Redland Green School and Dolphin Schools in Bristol; bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles Regiment; members of the Western Front Association and the Bristol Great War network and representatives of the Kingswood Association, whose generous donation enabled the plaque to be made and installed. Also attending were the Deputy Lord-Lieutenant for the County and City of Bristol, Colonel Andrew Flint and the Dean of Bristol, the Very Rev Dr David Hoyle. In total, around 100 people were in attendance for the ceremony. Afterwards a sizeable number of us were invited back to the Artillery Grounds on Whiteladies Road for light refreshments as guests of Bristol University Officer Training Corps.

Images of the unveiling ceremony can found below, followed by the culmination of much detailed research into Hardy’s life by Clive Burlton and myself. I can only hope that the people of Bristol and Bath embrace his memory. He deserves that.

Blue plaque for Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at 54, Salisbury Road, Redland, Bristol

Clive Burlton gives the opening address

Jeremy Banning providing the historical background to the life of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

The Lord Mayor of Bristol with members of Bristol University Officer Training Corps and bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles

A delighted Jeremy Banning and Clive Burlton with Hardy’s new blue plaque

The ceremony was well attended by the military

After the ceremony many of those attended were able to mingle and discuss Hardy’s life

Bristol 24/7 have also covered the story: https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/pictures-blue-plaque-revealed-wwi-soldier-redland/ as have BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-41918314. Our BBC Points West interview is available for a week from 16 minutes in here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b09bzw5f/points-west-evening-news-08112017

The life of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

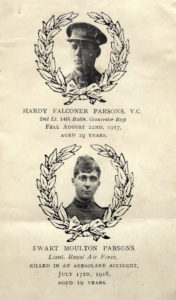

Hardy Falconer Parsons was born on 30 June 1897 at Rishton, near Blackburn, Lancashire, the first of three boys. His father, the Rev James Ash Parsons, was a Wesleyan Minister whilst his mother Henrietta (known as Rita) was the daughter of a railway inspector from York. Hardy’s rather unusual middle name came from Rita – Falconer was her maiden name.

The Rev James Ash Parsons had spent eleven years in total in the slums of East London as superintendent of the Methodist Leysian Mission. Ill health forced him and Rita to St Anne’s on Sea, south of Blackpool and it was whilst living here that Hardy was born. There followed three years at Arnside immediately south of the Lake District. Clearly, the ethos of duty and service to others, so well practiced by his parents, was a huge part of Hardy’s upbringing.

Hardy’s first school was King Edward VII School at Lytham St Annes. From the paper work we have found it appears the family moved to Bristol in 1912 when the Rev James Ash Parsons became pastor at the Old King Street Wesleyan Chapel (sadly, now demolished). The family moved to 54 Salisbury Road in Redland and Hardy attended Kingswood School in Bath until April 1915.

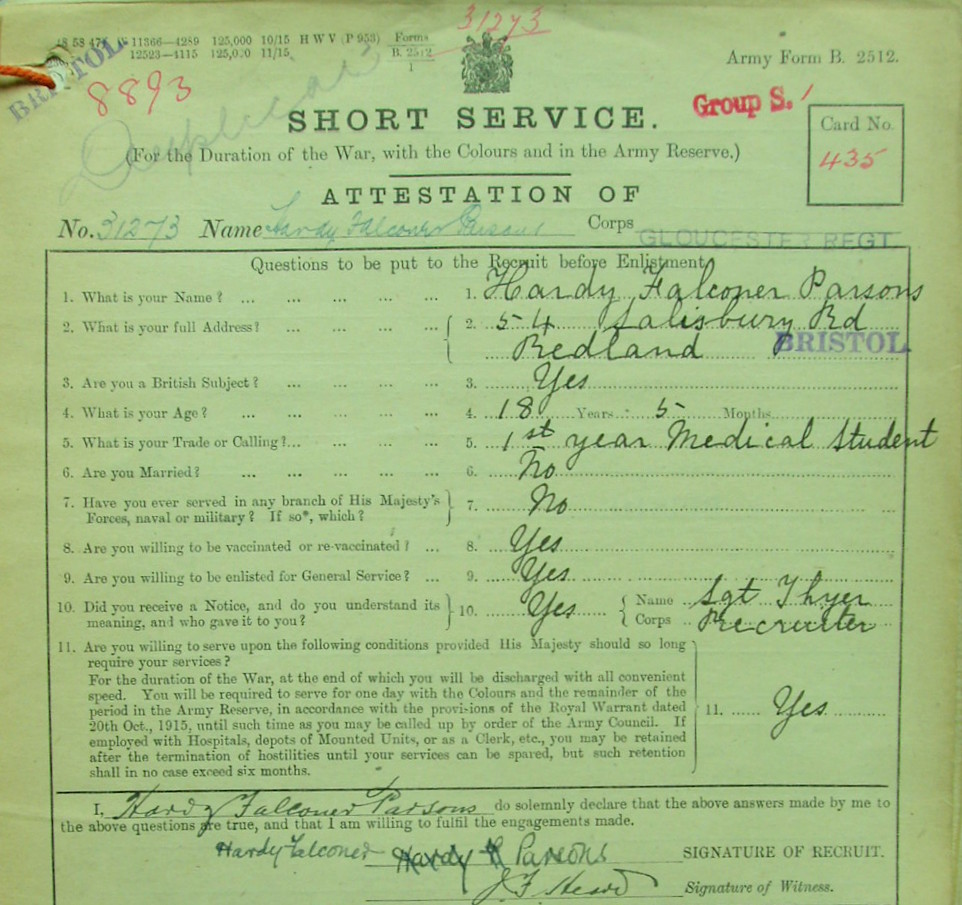

Extract from attestation papers of Hardy Falconer Parsons (National Archives: WO339/73298)

After school Hardy Parsons became a Medical Student at Bristol University with the aim of becoming a medical missionary. At the end of November 1915, during his first year at the University he signalled his wish to volunteer for service by attesting when aged just 18 years & 5 months but was immediately placed on the Army Reserve.

He had previously declined a safe post in a Government munitions laboratory, feeling that he ought not to withhold himself from the fullest sacrifice. He hated war, but recognised that the making of munitions was just as much war work as was the actual taking of life.

He joined the University’s Officer Training Corps in May 1916, a month shy of his 19th birthday, and then passed his first Bachelor of Medicine degree. His attestation papers make interesting reading – recording that he was a tall man, especially for that time, standing at 6ft ¾ inch tall. In early October 1916 he was posted to 6th Officer Cadet Battalion at Balliol College, Oxford and, on 25 January 1917, was appointed to the Gloucestershire Regiment as a Second Lieutenant.

He eventually joined the 14th Battalion in March, a unit which had previously been a ‘Bantam’ battalion – with men of 5ft 3 inches and less serving in its ranks. By the time the nearly 6ft 1 inch Hardy joined the battalion this unique distinction had been very much diluted. In February 1917 the battalion war diary records 475 ‘normal size men’ joining the battalion.

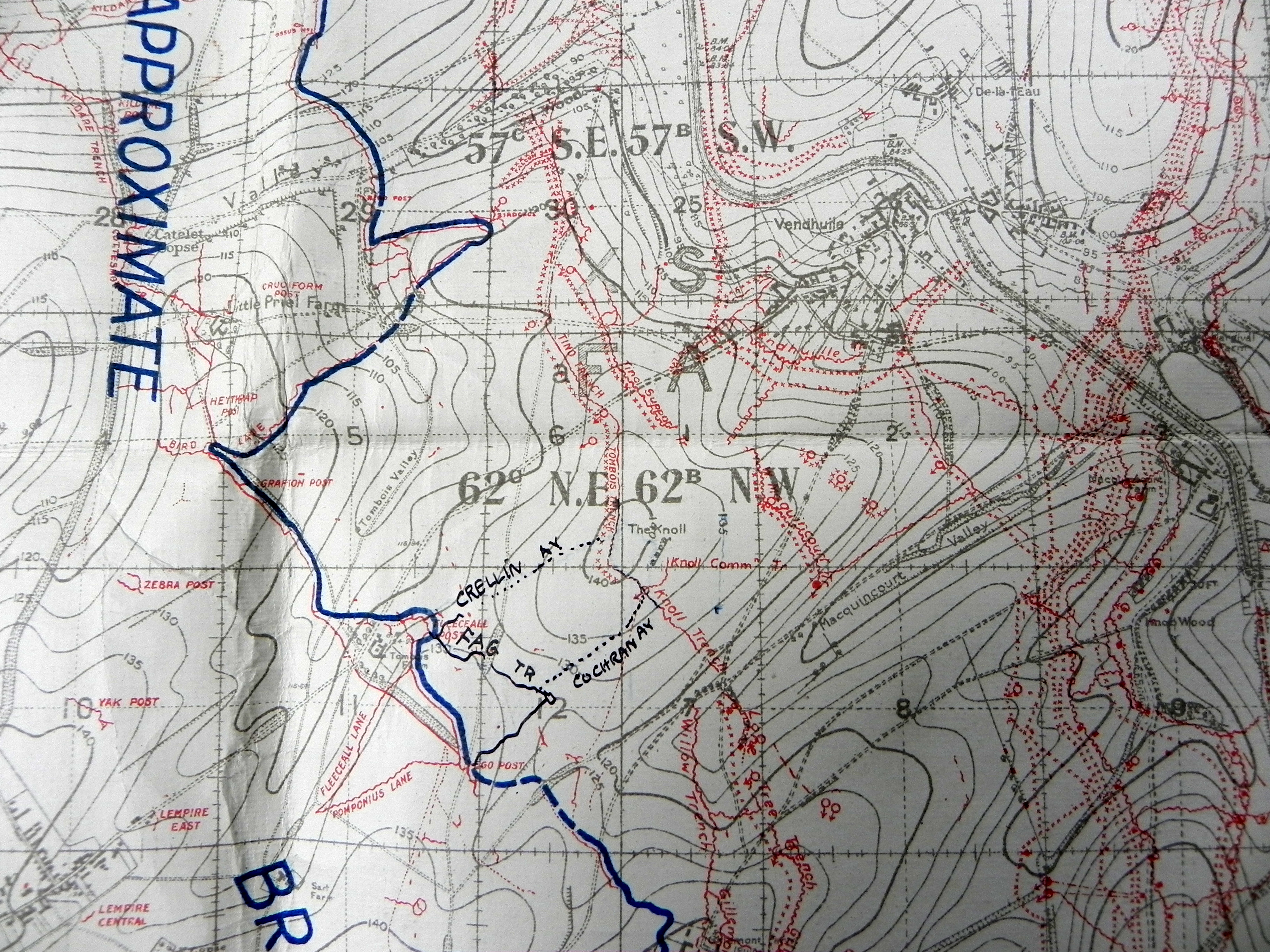

Trench map extract of The Knoll – captured by 105 Infantry Brigade on 19 August 1917

On 21 August 1917 near the village of Vendhuile in the eastern part of the Somme, Hardy’s battalion were holding recently captured trenches at a position known as The Knoll in the Hindenburg Line outpost zone. Their relief of the units who had captured the Knoll some two days before was completed by 1.30am that night.

Modern view of The Knoll, photographed October 2017. Vendhuile, the Hindenburg Line and St Quentin Canal are out of view in the valley.

It was a critical position which afforded observation over the Hindenburg Line and St Quentin canal a mile away – observation the British wanted and the Germans wanted to prevent. In fact, men from Bristol’s 1/4th and 1/6th Territorial battalions had fought for the same view in this same position four months previously.

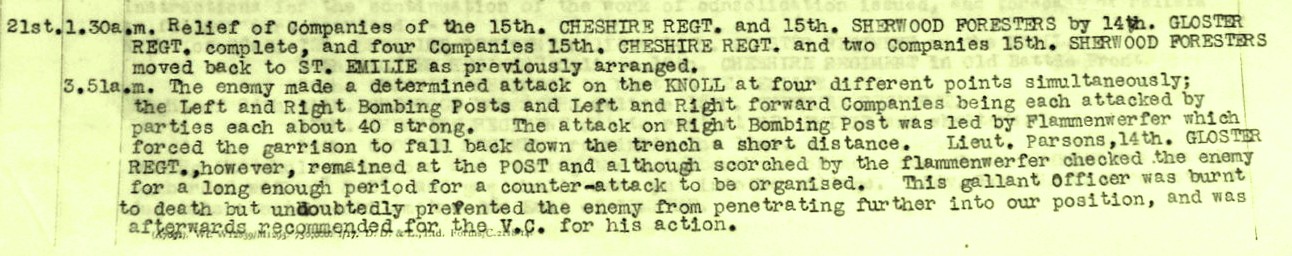

The loss of such critical terrain forced the Germans into a devastating counter-attack. As recorded in the Brigade war diary, at 3.51am the Germans struck. Militarily, it was a brilliantly executed counter-attack by the Germans – The Knoll being attacked at four points simultaneously. German infantry were accompanied by special detachments using portable flamethrowers. These forced Hardy Parsons’ men back. However, he alone stuck to his bombing post and held his position, throwing bombs (hand grenades) at approaching Germans until a British counter-attack could be launched. The counter-attack was successful – the Germans were repulsed from the trenches around The Knoll and within 40 minutes this bloody action was over. Much of this success is due to Hardy’s refusal to yield ground.

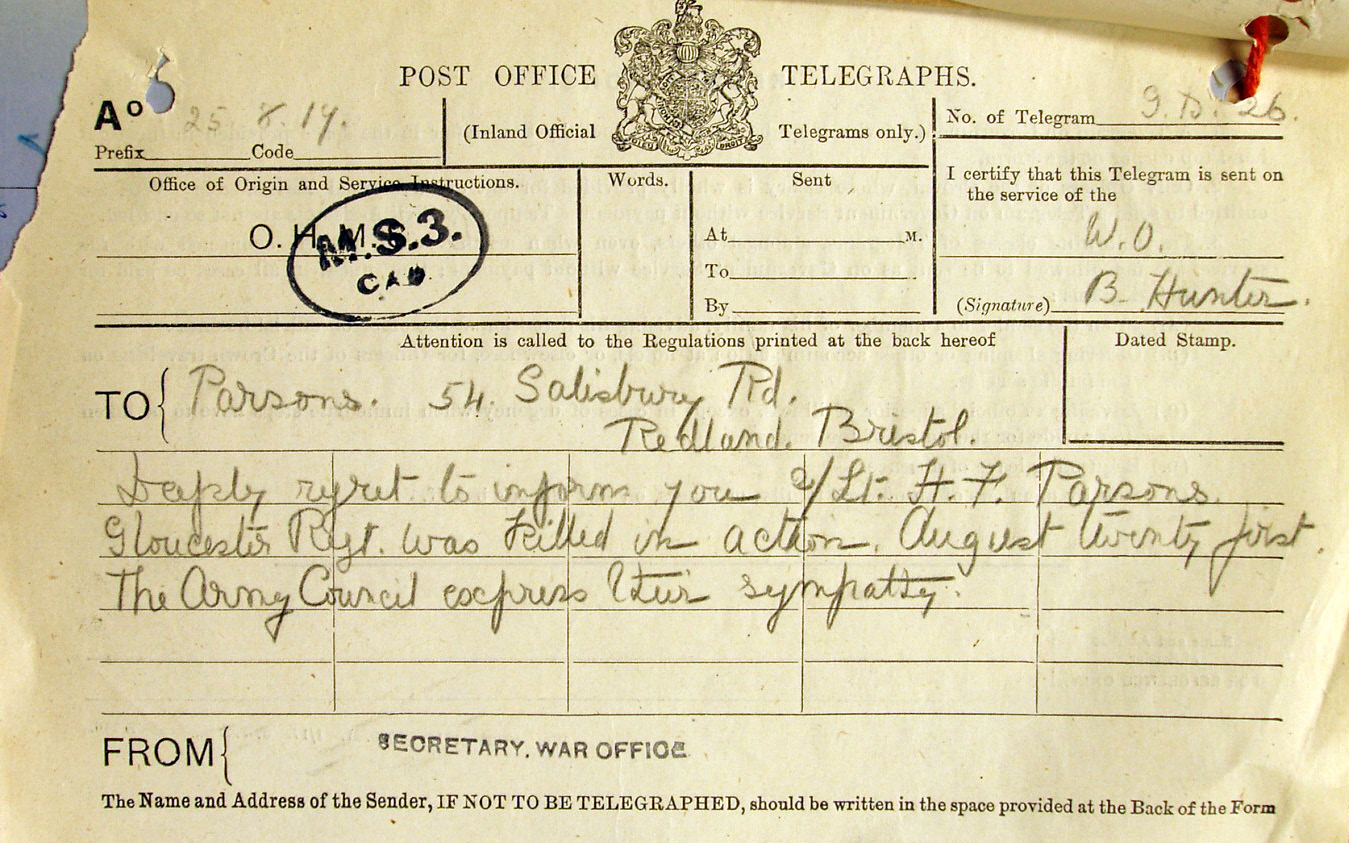

Telegram sent to the Rev James Ash Parsons informing him of Hardy’s death

During his heroic sole defence of The Knoll Hardy had been severely burnt by liquid fire. Writing these words over a hundred years later I cannot begin to imagine the sense of duty that compelled him to stay at his post, or the pain he would have endured during and after sustaining such horrific burns. Unsurprisingly, the nature of his wounds proved too severe and he succumbed later that day, dying at the age of just 20 years and two months. Hardy Falconer Parsons is buried in the immaculate CWGC cemetery at Villers-Faucon.

N.B. I was contacted in August 2019 by Dr Markus Schroeder whose great great uncle, Ernst Komander, served with the 2./Jäger 6, Jäger-Regiment 6, 195 Infanterie-Division. He tells me that regimental records show it was Jäger-Regiment 6 that led the attack on the 14th Gloucesters with the specialist flamethrowers employed by Sturmbataillon 3. Ernst Komander was wounded on the day of the attack and died of those wounds two days later. He is buried in Block 2, Grave 56 in Caudry German Military Cemetery.

Grave of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at Villers Faucon Communal Cemetery

Hardy’s effects, consisting of just a wrist ID disc and two wrist watches were sent by registered post to his father within the month.

105 Infantry Brigade war diary describing the events of 21 August 1917

The Brigade diary describes Hardy’s gallantry, commenting that he ‘was afterwards recommended for the VC for his action’. During the war many acts of bravery were put forward for the VC but subsequently rejected. However, in Hardy’s case, approval was given. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross – personally presented to his father by King George V at a ceremony on Durdham Down (Bristol) on 8 November 1917. Hardy’s father also attended the Colston Hall event on 15 February 1919 when he was presented, on his dead son’s behalf, with an illuminated address and gold watch by Lord Mayor Twiggs. The address included Hardy’s full Victoria Cross citation:

“For most conspicuous bravery during a night attack by a strong party of the enemy on a bombing post held by his command. The bombers holding the block were forced back, but Second Lieutenant Parsons remained at his post, and, single-handed, and although severely scorched and burnt by liquid fire, he continued to hold up the enemy with bombs until severely wounded. This very gallant act of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty undoubtedly delayed the enemy long enough to allow the organisation of a bombing party, which succeeded in driving back the enemy before they could enter any portion of the trenches. This gallant officer succumbed to his wounds.”

Hardy Parsons was only the second member of the Gloucestershire Regiment to receive a VC during the First World War.

Hardy Falconer Parsons VC Chapel Memorial, Kingswood School, Bath

On 23 July 1923, a tablet in his memory was unveiled in the chapel of Kingswood School in Bath and his Victoria Cross and campaign medals are held by the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, having been presented to the Gloucestershire Regiment at a ceremony in 1970 in front of what is now City Hall, attended by the Lord Mayor, Cllr Bert Wilcox.

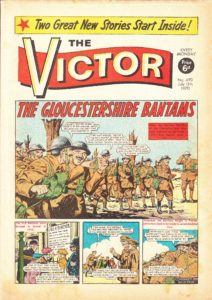

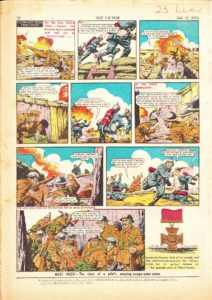

Victor comic, 11 July 1970 – the story of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

The collection also includes a portrait photograph of Hardy in uniform; the bronze memorial plaque sent, popularly known as the “Dead Man’s Penny” to his parents after the war and his Gloucestershire Regiment collar badge. Engraved on the back of the badge are the words “Irene Randall 10 Newfoundland St., Bristol 1917”. Who she was, and why he had that, we will probably never know….

Victor comic, 11 July 1970 – the story of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

On 11 July 1970, the Victor Comic ran a cartoon story with 10 sketches on its front and back pages, recounting the story of the 14th Gloucesters action at The Knoll and to the deeds of Hardy Falconer Parsons – bringing his heroic actions to the attention of a younger audience.

Ewart Moulton Parsons

And as for the Parsons family, despite Hardy’s death, the war had not finished with them. Hardy had two younger brothers; Ewart Moulton and Lyall Ash. Lyall was born too late to serve but Ewart, born the year after Hardy, was working as an apprentice engineer at Bristol company, Brecknell Munro and Rogers in summer 1916.

Page from memorial booklet for Hardy and Ewart Parsons

He joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and by 17 July 1918, was a 19 year old Lieutenant and pilot in No.50 Training Depot Station at Eastbourne, flying his Sopwith F1 Camel fighter high above the Seaplane Station. What happened next is still unclear but his plane went into a spin and plummeted to the ground from 3000ft. Unsurprisingly, Ewart was killed instantly.

Grave of Ewart Parsons in Canford Cemetery, Bristol

His body was brought back to Bristol and his funeral held at the Old King Street Wesleyan Chapel where his father was the pastor. The coffin was borne by six RAF officers and taken on a gun carriage to Canford Cemetery, where the internment took place followed by the sounding of the Last Post.

So, in the space of eleven months James Ash and Rita Parsons had lost two of their three boys. On the base of the stone cross marking Ewart’s grave at Canford Cemetery the family also commemorated his brother, Hardy. Like so many families across the world, the Parsons’ suffered grievously in the war.

Detail on Ewart Parsons’ grave in Canford Cemetery

But, as this research is primarily based on Hardy I would like to end with a description of him, provided by his father which, when considered alongside his Victoria Cross action, shows him to have been a truly remarkable young man, a perfect example of the loss of the best of that generation:

“Hardy lived all of his life from early childhood on the same high plane of self-forgetfulness and sacrifice in his thought for and service of others”

Hardy Falconer Parsons VC (30 June 1897 – 21 August 1917)

Sources of information consulted for this article include:

Service record of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC (National Archives: WO339/73298)

105 Infantry Brigade War Diary (National Archives: WO95/2486)

14 Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment War Diary (National Archives: WO95/2486)

RAF service record of Ewart Moulton Parsons

Census returns (1901 & 1911)

Material from the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum http://www.soldiersofglos.com/

Victor Comic, 11 July 1970

London Gazette – various dates

The Kingswood Magazine, Vol. XX, No.10, December 1917

North Devon Journal, 27 August 1931

North Devon Journal, 10 November 1949

Gliddon, Gerald, VCs of the First World War: Cambrai 1917, Stroud, 2004

Second Lieutenant Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. Image courtesy Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Ref GLRRM:04750.6

On 8 November 2017 a Bristol Civic Society Blue Plaque for Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment (my local Victoria Cross recipient) will be unveiled at 54 Salisbury Road, Redland, Bristol. The date is 100 years to the day after King George V personally presented Hardy’s VC to his father, Rev James Ash Parsons at a ceremony on Durdham Downs.

Between 2014 and 2019 the Government is funding the production and placing of a commemorative stone for each and every Victoria Cross recipient of the First World War. Although Hardy Falconer Parsons lived at 54 Salisbury Road, he was not born in Bristol. So in August the government-funded commemorative stone relating to Hardy Parsons, was laid in Rishton, Lancashire.

Local historian and author Clive Burlton and I were determined to see Hardy’s strong association with Bristol and the West Country recognised. If we couldn’t have the government-funded stone in Bristol, the next best thing was to have a Bristol Blue plaque unveiled in his honour.

The grave of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at Villers-Faucon Communal Cemetery

So, during the past year we have organised for the creation of the plaque. Wednesday’s ceremony, starting at 11am, will have representatives from the Bristol Civic Society; the former Gloucestershire Regiment; the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum; the Bristol University Officer Training Corps; Kingswood School, Bath, Redland Green School and Dolphin Schools in Bristol; bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles Regiment; the Western Front Association; members of the Bristol Great War network and representatives of the Kingswood Association, whose generous donation enabled the plaque to be made and installed. Also attending are the Lord Mayor of Bristol, Cllr Lesley Alexander; the Deputy Lord-Lieutenant for the County and City of Bristol, Colonel Andrew Flint and the Dean of Bristol, the Very Rev Dr David Hoyle.

The event is open to the public so please do come along and attend if you can. I will be posting the results of my research on Hardy Parsons along with photos of Wednesday’s ceremony on my website later this week. In the meantime, it is worth reading Hardy’s VC citation to have an idea of his valour:

“For most conspicuous bravery during a night attack by a strong party of the enemy on a bombing post held by his command. The bombers holding the block were forced back, but Second Lieutenant Parsons remained at his post, and, single-handed, and although severely scorched and burnt by liquid fire, he continued to hold up the enemy with bombs until severely wounded. This very gallant act of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty undoubtedly delayed the enemy long enough to allow the organisation of a bombing party, which succeeded in driving back the enemy before they could enter any portion of the trenches. This gallant officer succumbed to his wounds.”

There should be a short film on Hardy’s action on Wednesday evening’s Points West (BBC1) from 6.30pm.

Researching the war service of Ioan Gruffud’s Great Great Uncle, Rhys Griffiths, for BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’

Back in May I spent an afternoon filming with Yellow Duck Productions for their hit BBC Wales genealogy series, ‘Coming Home’. The programme, which was shown on at 9pm on BBC One Wales on Wednesday 21 December was an hour-long special, looking at the family history of Hollywood actor Ioan Gruffud. Whilst it unlocked stories of Ioan’s royal connections it was his Great Great Uncle Rees (known as Rhys) Griffiths’ service in the Great War which I had been asked to research and explain.

Ioan Gruffud & I outside the church in Pontyberem

Rhys was the son of David and Anne Griffiths, of Meilog, Pontyberem. A keen churchgoer, at the outbreak of war he was studying to enter the ministry. He enlisted at Carmarthen in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) and was posted to 106 Field Ambulance, part of the 35th Division (made up of ‘Bantams’ who were all under the normal regulation minimum height of 5’ 3”). With his unit, he moved to France early in 1916, occupying positions in the trenches in French Flanders and Artois. Sadly, there is no surviving service record for Rhys and so his day-to-day movements can only be pieced together from his unit war diary.

63926 Pte Rhys Griffiths, 106 Field Ambulance RAMC

The war diary for 106 Field Ambulance is often short and functional, describing the routine of the subsequent months with little elaboration but noting issues involving latrines, dung heaps, a lack of coal for hot baths and too few disinfectors to help prevent scabies and lice. At the end of May 1916 this period of relative calm ended abruptly.

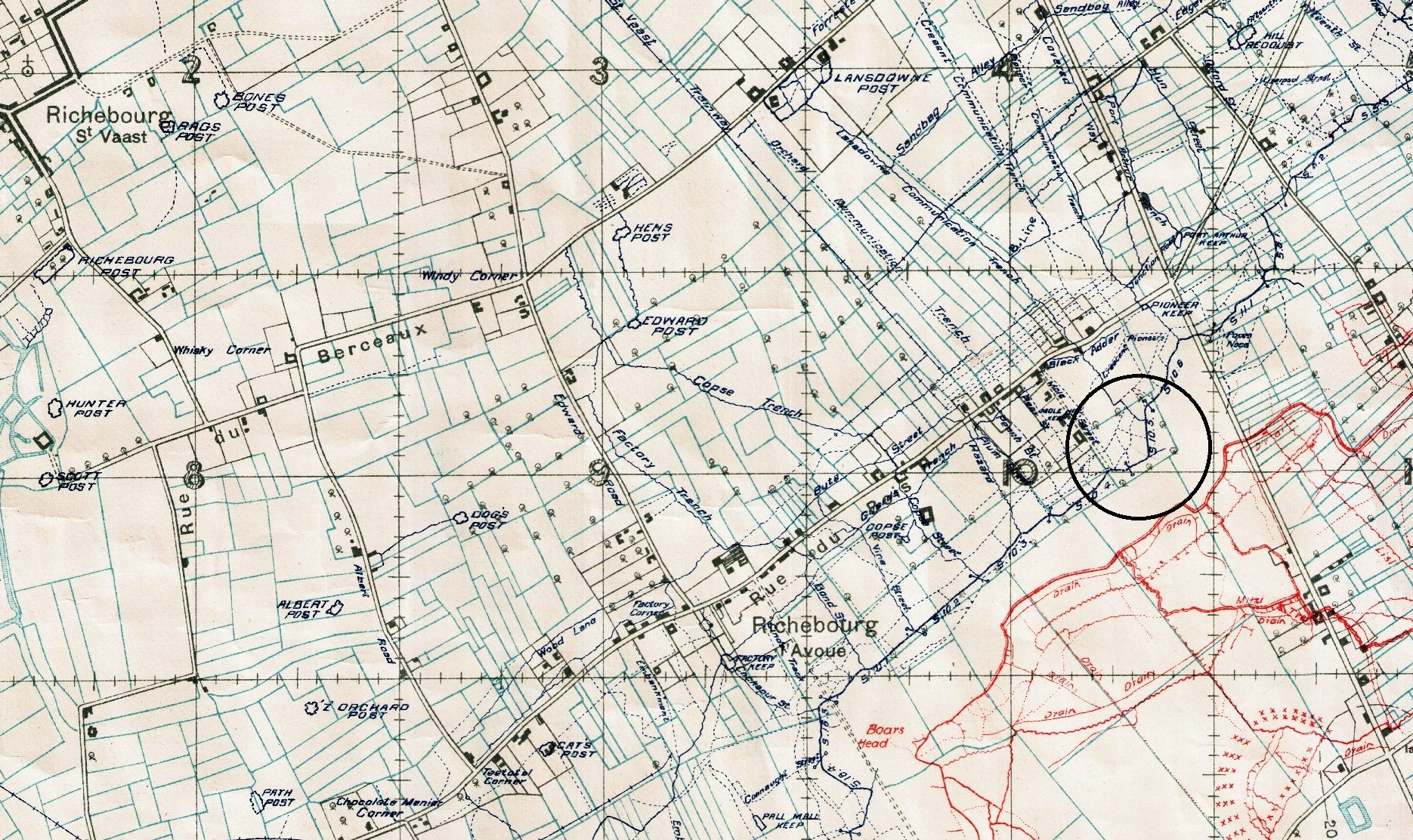

On the night of 30 May 106 Field Ambulance are serving in the Rue du Bois sector between the villages of Neuve Chapelle and Festubert. At this time these villages, both heavily fought over in 1915, were considered a relatively ‘quiet’ sector.

At 7.20pm that night a heavy German bombardment falls on the frontline trenches around the salient around S10.5, destroying 250 yards of breastwork trenches. Further artillery fire falls on support positions, ‘bracketing’ the area and preventing British reinforcements getting through. Under this bombardment the infantry holding this sector, W Company of 15th Sherwood Foresters, suffer heavy casualties and it is reported three officers are wounded. One of these, Captain Ralph Ainsworth is wounded twice.

Trench map with S10.5 circled

The barrage is a precursor to a highly successful raid by the enemy. By 8.40pm, with positions destroyed and most of the Sherwood Foresters wounded, German troops attack, penetrating the right flank of the position and taking a number of men prisoner. By 10.10pm men of the 14th Gloucesters and 18th Lancashire Fusiliers had re-established British control of the salient.

By then, Rhys had been killed. The exact circumstances surrounding his death are provided by a letter written by Frank Fairfax, the Chaplain of the Field Ambulance, to Rhys’ father which was later published in The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Advertiser of 8 September 1916:

Dear Mr Griffiths, I have to break the sad news to you of the death of your son, Rhys, on the night of 30 May. In the bombardment of the trenches there were many wounded, and he and his friend, Dugdale, were together giving first-aid and carrying the wounded back to safety. As I understood it was while Rhys and Dugdale were attending the wounded officer that a shell burst which killed Rhys, but left Dugdale unharmed except for a severe shock. When he is well enough he will be writing to tell you about it. But there is no doubt order tramadol online 180 that Rhys showed great bravery, and thought not of himself in his noble devotion to duty. I knew him and loved him. He was known to be a splendid comrade and a true Christian. Often he would sing to us his Welsh songs and hymns.

The German raid was very well planned and executed. Raids such as this were a common enough event, even in ‘quiet’ sectors. Their usual aims were to kill the enemy, gather intelligence on defences and, if possible, capture prisoners who could be interrogated for additional information.

A report written the following day by Lt Colonel RNS Gordon, 15th Sherwood Foresters details two Officers and thirty-four Other Ranks still unaccounted for. A subsequent report provides a detailed narrative of events and lists Officers and men who showed gallantry during the raid. First on the list is Captain Ainsworth (the twice wounded officer) who the report describes as ‘although wounded twice refused to be moved and stayed with his Company until the end. He displayed remarkable coolness and apparently only gave the orders to withdraw to the flanks as a last expedient.

He further took steps to see that all documents and the logbooks were sent to Headquarters on realizing the gravity of the situation.

He is, I regret, still missing.’

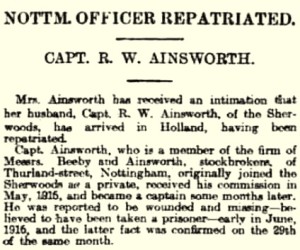

Nottingham Evening Post – Monday 22 April 1918

In fact, he stayed missing – at least to the British. Records show Captain Ainsworth was captured by the raiding party. He was held by the Germans in Officers’ Detention Camps at Crefeld and Holzminden until April 1918, when he was transferred to Holland, finally being repatriated in December of that year. Notification of his transfer to Holland reached the Nottingham press on 22 April (shown to the left). A Facebook page ‘Small Town, Great War. Hucknall 1914-1918’ gives more detail on Captain Ainsworth here.

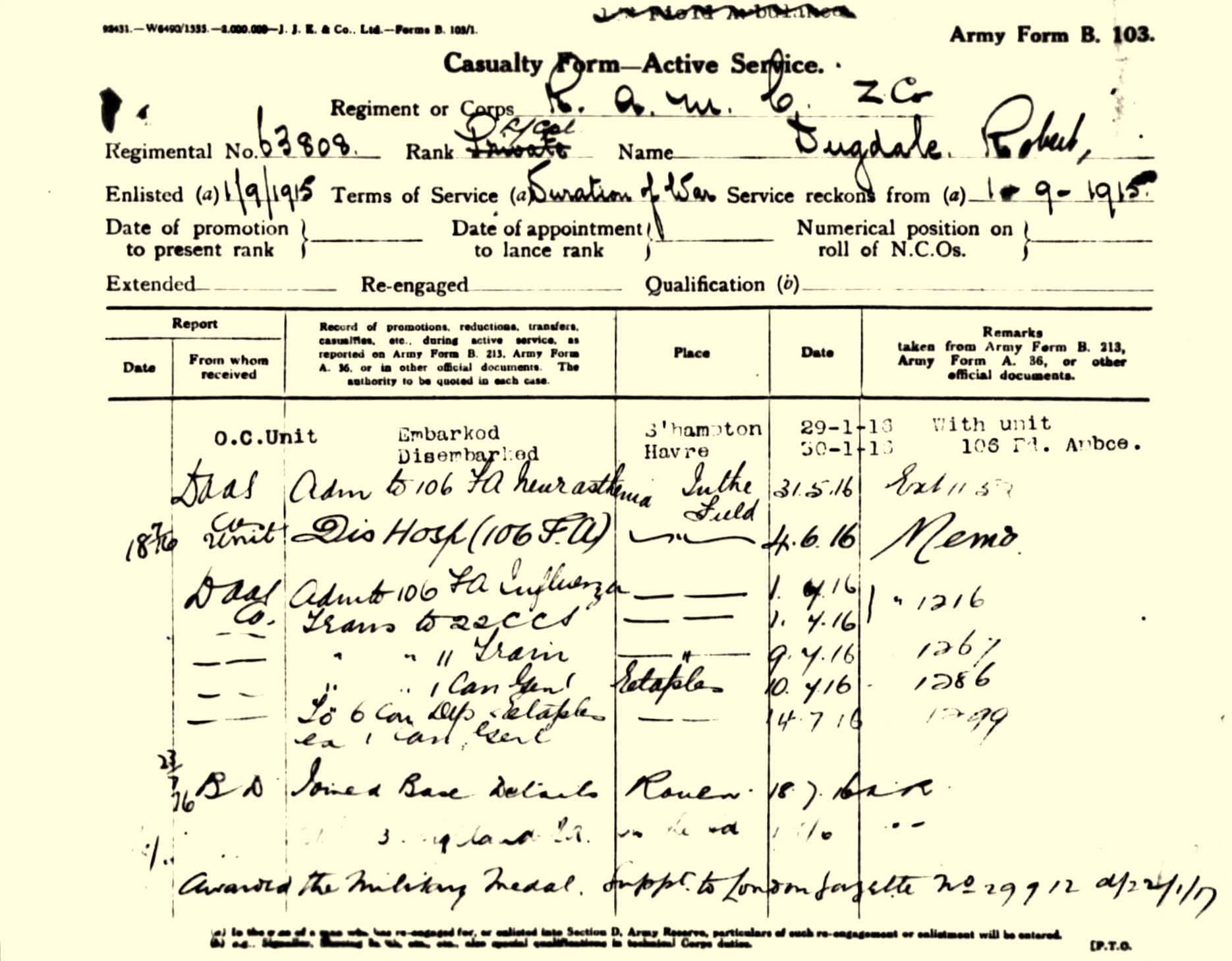

As the chaplain’s letter describes Rhys and Dugdale attending a wounded officer when Rhys is killed, there is a good chance the officer was Ainwsworth. The letter also describes Rhys’ RAMC comrade, Private Robert Dugdale, being severely shocked. Dugdale’s pension record survives and confirms the chaplain’s description of events. He was admitted to the Field Ambulance as a casualty that night, suffering with neurasthenia. Dugdale makes a full recovery, serves through the Somme, Passchendaele and the 1918 battles, ultimately surviving the war. Having served nearly four years he was discharged in July 1919. Dugdale was awarded the Military Medal in January 1917, probably for good work during the Battle of the Somme.

Casualty Form from Robert Dugdale’s Pension Record showing his admission to the Field Ambulance with neurasthenia

Rhys Griffiths was the first death suffered by 106 Field Ambulance since their arrival in France. The other two men known to be associated with his death, Private Robert Dugdale and Captain Ralph Ainsworth, both survived the war. Such is the way luck can play a part in surviving time in the trenches. Despite it being a tragic story, it was a satisfying experience to talk Ioan and his father Peter through Rhys’ all too brief period of time on the Western Front. Another family now aware of their link to the Great War.

Rhys is buried in St. Vaast Post Military Cemetery, Richebourg L’Avoué alongside the men of 14th Gloucesters and 15th Sherwood Foresters who also died on 30 May 1916. Remembering them all.

Grave of Pte Rhys Griffiths, 106 Field Ambulance RAMC at St. Vaast Post Military Cemetery, Richebourg L’Avoué

Link to BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’ page: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b086xl8v

Introduction

Few places on the Western Front held such a reputation as the Hohenzollern Redoubt. Attacked by the 9th (Scottish) Division at the start of the Battle of Loos on 25 September, the redoubt, jutting out into No Man’s Land was fiercely defended. It is perhaps most well known as the scene of the disastrous 46th (North Midland) Division’s attack on 13 October 1915. The losses to the 46th Division of 3,763 officers and men that day are greater than sustained in their failed attack at Gommecourt on the First Day of the Somme on 1 July 1916. Following the failure of this attack the line stabilised and the Hohenzollern Redoubt soon developed into a vicious mining sector as tunnelling operations reduced the landscape to a sea of huge mine craters.

Modern map showing the Loos battlefield. Auchy-les-Mines can be seen south of the La Bassée canal. The Hohenzollern Redoubt was not far from the road passing Cité Magdagascar running to Vermelles.

The Battle of Loos

However, it is one event between the Scots’ initial attack and the 13 October endeavour that is the subject of this article. The Scots’ success in penetrating the German positions had been bought at a heavy price. Troops of the 26th Brigade had taken the Redoubt and pushed north to Fosse 8 and the Dump. German counter-attacks reversed these gain, pushing the Scots back to the eastern face of the Hohenzollern Redoubt by the end of following day. Severely depleted from their action, the Scots handed over their tenuous gains to the 28th Division, the positions being taken by units of the 85th Brigade.

Fierce fighting continued for the next three days with German counter-attacks slowly and painfully retaking trenches. At the end of 30 September the British occupied the West Face of the Redoubt and Big Willie Trench. The Germans controlled most of Little Willie Trench, threatening the north flank of the Redoubt. On the night of 30 September/1 October 84th Brigade relieved 85th Brigade. German observation of this relief from the heights of the Dump was total and the new British occupants were subjected immediately to strong bombing attacks. The British held on – but only just.

That night, they would attack to improve their hold on the German trenches. The plan was risky, involving no artillery bombardment. The attacking force captured parts of Little Willie Trench but could advance no further. German retaliation was swift; artillery subjected the Redoubt and Little Willie to regular and heavy trench mortar fire. A German bombing attack retook Little Willie Trench, followed by the loss of the Chord and West Face. Other than a small section of Big Willie Trench, the British were for the most part back in their original lines. The blood-soaked redoubt would have to be assaulted again.

The 1st King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry into the line

The 1st Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (83rd Brigade, 28th Division) had fought with great aplomb at Second Ypres. Prior to the Battle of Loos the battalion had been holding trenches on Messines Ridge. Their move south, via Bailleul and Outtersteene brought them to Noyelles les Vermelles on the afternoon of 27 September. The following afternoon they occupied reserve trenches on the Vermelles road as a bombardment was expected. After 90 minutes in position they returned to their billets in Noyelles.

On the morning of 29 September the Battalion moved forward. B & C Companies occupied Sussex Trench whilst Battalion HQ and the remainder of the unit stayed in the Lancashire lines. In the afternoon B & D moved up to the line, D Company in the firing line in BIG WILLIE trench with B Company in support. Later that afternoon, the remainder of the Battalion moved up to the reserve trenches.

Having taken twelve casualties the battalion were relieved the following day. They proceeded to the old British front line north of the Hulluch road, arriving there at 2.15am on 1 October. Three and a half hours later the Battalion were ordered to move up and occupy the old German buy real ambien online front line trenches. Later that day they were relieved by 2nd Highland Light Infantry and proceeded to billets at Annequin. On the morning of 3 October the Battalion marched to Vermelles and then into trenches opposite the redoubt to relieve the 6th Welsh (84th Brigade).

Trench map showing Hohenzollern Redoubt, The Dump and Fosse 8. British lines in blue, German lines in red.

Attack

That night the C.O., Lt-Colonel C.R.I. Brooke DSO and Major Mallinson DSO went to Brigade HQ. An attack was to be made at 4.45am on 4 October by three battalions; the 1st KOYLI and 2nd East Yorkshires would attack the redoubt frontally, leaving the 2nd King’s Own to capture and consolidate Big Willie Trench. The optimistic plan depended on darkness providing the assaulting parties with the necessary element of surprise. Even then, the British would be advancing into a tumbled maze of trenches. The assaulting troops had no idea what they would be facing; there had been no time to reconnoitre the position.

At 4.15am the first two waves of the 1st KOYLI were in position thirty yards in front of their trench. Fifteen minutes later a third wave followed. The 2nd East Yorkshires deployed similarly. Battalion war diaries mention a distinct lack of artillery fire. Whatever shelling there was had no discernible effect on the German trenches. The Battalion War Diary for 4 October records the attack thus:

A & D Coys ordered to attack HOHENZOLLERN REDOUBT

4.45am – A & D attacked and were met with very heavy machine gun and rifle fire. There was no artillery bombardment. The distance to the German line was about 200 yards and the men got half way across. By then they were practically wiped out.

These few lines make grimly predictable reading. Traversing 200 yards of open ground swept by machine-gun fire proved impossible. The war diary records the following casualties:

2/Lt A.H. Martindale 1st KOYLI killed

2/Lt C.L. Pearson 1st KOYLI wounded

2/Lt F.W. Graham 4th DLI, attached 1st KOYLI missing

2/Lt P.J.C. Simpson 3rd KOYLI, attached 1st KOYLI missing

Other Ranks – killed 10, wounded 65, missing 101

It concludes by noting ‘There is no doubt that most of the missing were killed. A few wounded were got in during the night 4th/5th.’ Losses to the East Yorkshires and 2nd King’s Own were equally heavy. The attack stood no chance of success. Following their mauling the Battalion were relieved by the 1st Coldstream Guards the next day. This move signalled the relief of the 28th Division by the Guards Division. In a week the Division had suffered over 3,200 casualties. There is no after action report in the 1st KOYLI diary but the summary given by Lt-Colonel Blake, 2nd East Yorkshires whose men attacked alongside the 1st KOYLI is damning, attributing the failure of the attack to the following causes:

(i) No Artillery bombardment

(ii) Complete lack of element of surprise. The Germans were well prepared, and had not been in the slightest shaken by the desultory shelling that had taken place throughout the day.

(iii) The Germans had been digging in during the day previous, and had thoroughly improved their trenches.

(iv) The relief the day before did not finish until 7pm. Company officers had only very indistinct idea of the trenches they were occupying, and none at all of the positions they were to attack.

So, when next at Vermelles, Auchy and the site of the Hohenzollern Redoubt give some thought not only to the Scots who attacked on 25 September 1915 and the North Midlanders (with two divisional memorials – one at Vermelles and one close to the redoubt) who fell is such number on 13 October but also to the men of the neglected 28th Division.

Following their exploits at Loos the 28th Division was moved to the Salonika front, sailing from Marseilles on 26 October 1915. Recommended reading includes Andrew Rawson’s ‘Loos 1915: The Northern Battle and Hohenzollern Redoubt (Battleground Europe)’

In memory of 21865 Private George William Williams, 1st KOYLI. Killed 4 October 1915, buried Arras Road Cemetery, Roclincourt.

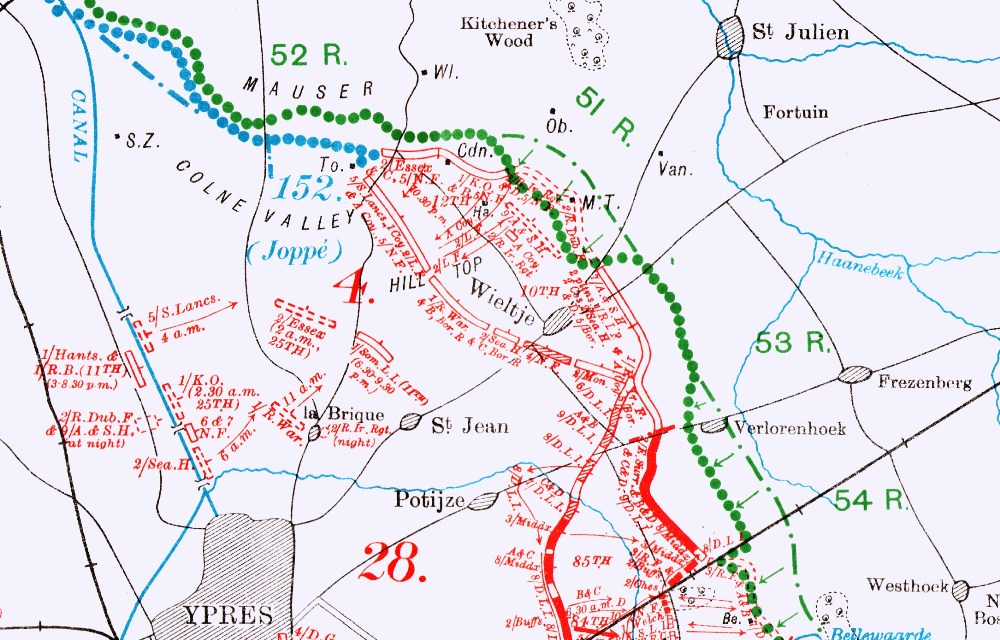

This brief article will look at the actions and casualties sustained by the 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers (part of 10th Brigade, 4th Division) during the Second Battle of Ypres. One often feel when visiting the Ypres Salient that the sheer horror of the Third Battle (Passchendaele), fought during the summer and autumn of 1917, can overshadow earlier clashes. Many first-time visitors may be unaware of the horrendous casualties sustained by the British in earlier desperate defensive battles (First Ypres – Oct-Nov 1914) and Second Ypres (April-May 1915). The latter battle saw the advent of chemical warfare when the Germans released chlorine gas on a four mile frontage in the late afternoon of 22 April against two French divisions defending the north of the salient. Gas also drifted across Canadian positions holding the left flank of the British. The initial success of this experimental weapon, which left a trail of dead and dying in its wake, enabled the Germans to advance from the fields around Poelcapelle and Langemarck to Steenstraat on the Yser Canal. The stalwart defence of the untried 1st Canadian Division (my grandfather, a private in the 13th Battalion CEF, amongst them) and the rushing forward of British troops to plug the gap around Ypres is not the subject of this article. However, this defence must be appreciated to put the specific story of the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers into context. Not surprisingly, considering their initial success, the Germans used gas on a number of other occasions during the battle, culminating in the Battle of Bellewaarde Ridge on 24-25 May. A terrifically detailed description of the opening phase of Second Ypres can be found here: http://www.greatwar.co.uk/battles/second-ypres-1915/index.htm.

Into action

On 23 April 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers were told to stand by and be prepared to move at a half hours notice. The following day they marched via Vlamertinghe to the outskirts of Ypres and at midnight to St Jean where they deployed west of the Wieltje – St Jean road at 4am. The Battalion War Diary records they suffered heavy casualties digging in on a line a quarter of a mile from and facing St Julien. There follows a ‘quiet morning up to 11am’ until the Northumbrian Infantry Brigade attacked through their trenches. During this period Captain Banks was killed, his command being assumed by Captain Basil Maclear. The War Diary records ‘heavy shelling throughout the day, and intermittent musketry’. There follows a few days of relative quiet which is shattered on 2 May when, in a foretaste of future action, the enemy attacked under cover of gas. Men of the left hand company were most affected but the German attack failed to reach the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers trenches.

After relief on 4 May the Battalion bivouacked on the east bank of the Yser Canal, a half mile north west of La Brique. This period away from the front line was shortlived as the Germans made a concerted effort to break the British line. This attack, made against the 27th and 28th Divisions on 8 May, began what was named by the post-war Battles Nomenclature Committee, the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge. A violent German artillery bombardment caused terrible destruction to the British defences. Whilst avoiding this initial bombardment the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers were warned at noon to be prepared to move forward to support 81st Infantry Brigade. Ninety minutes later the battalion (in fighting order) left their bivouac and joined the 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment outside Ypres, moving to the wood by Potijze Chateau. Heavy shell fire was recorded throughout the afternoon and evening. On three separate occasions the Battalion deployed beyond the British barbed wire to assault the German trenches North of Potijze Woods. Each time the attack was cancelled. However, the body of men in the open presented an easy target for German machine gunners; the War Diary records that ‘machine guns did considerable damage’. To compound the misery the rations failed to arrive.

That night the battalion occupied what was left of the GHQ Line, their left being 150 yards south east of Shell Trap Farm (later renamed Mouse Trap Farm), lying immediately north of the Wieltje – St Julien road. One company was held in reserve in trenches north of Potijze Wood. The War Diary describes 9 May as “One of the worst days shelling [the] Battalion experienced.” German machine gun and accurate sniper fire added to the difficulties. After a few days in these positions the Battalion was relieved, moving back to Vlamertinghe Chateau before returning to the trenches on 19 May. The War Diary records little of interest in the following few days other than intermittent shelling and sniping. The entry for 23 May records a “Quiet day and night”. The Dubliners were not know it but that quiet night was the calm before the storm.

Shell Trap Farm – 24 May 1915 gas attack (The Battle of Bellewaarde Ridge)

Official History map showing position occupied by 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers at Shell Trap Farm, 24 May 1915

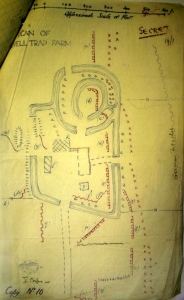

Detailed sketch map showing trench positions around Shell Trap Farm prior to 24 May gas attack. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diay (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

At 2.45am on 24 May the enemy attacked with gas. The area round Shell Trap Farm and to its immediate north west was most affected. A detailed report of the events of 24 May 1915 by Captain Thomas J Leahy (incorrectly transcribed as Linky in the report) is attached to the Battalion War Diary. Leahy describes that their C.O., Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Loveband has suspected gas may be used when inspecting the trenches at Shell Trap Farm earlier that night. He had personally warned all Company officers to be prepared whilst Major Russell (RAMC) had inspected all that Vermoral sprayers and warned each company about damping their respirators. Leahy’s report notes there were ten sprayers in working order that night, one with each machine gun and the remainder distributed along the trenches.

When seeing red lights thrown up from the German trenches (a signal for the gas release) Lt-Col Loveband shouted “Get your respirators boys, here comes the gas”. Leahy notes how little time they had; “we had only just time to get our respirators on before the gas was over us”. There was a gentle breeze, the gas cloud being very dense took about three quarters of an hour to pass over the Fusiliers’ position. German parties advanced in small numbers at 4.30am, occupying the British line north and to left of the Battalion’s trenches. With these trenches occupied, the Battalion was now subjected to enfilade fire. Under heavy shellfire and aided by part of two companies of the 9th Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders the Battalion held to their trenches to the end. The report makes harrowing reading, containing transcripts of signals sent by isolated parties within the farm complex. Even a hundred years after the event it is clear to sense the fear in 2nd Lieutenant Robert Kempston from B Company’s message which simply stated “For God’s sake send us some help. We are nearly done”. Kempston was killed later that day. Whilst speaking to officers outside his dugout Lt-Colonel Loveband was also killed when a bullet struck him through the heart.

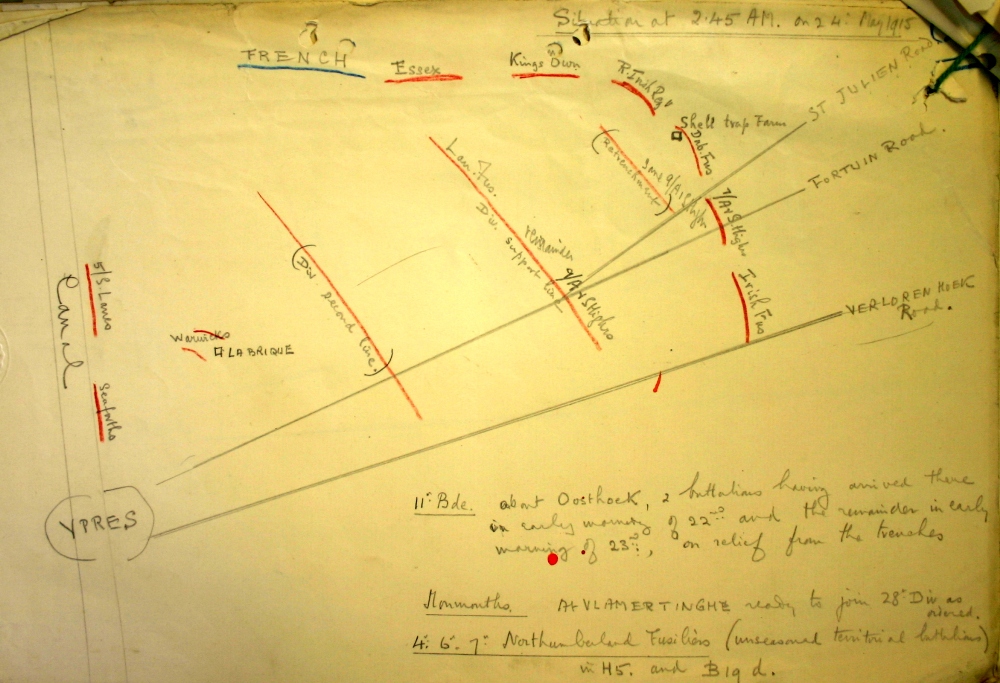

Sketch map showing situation at 2.45am on 24 May 1915. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diary (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

The War Diary records “Germans advancing under cover of enfilade fire, in small parties, finally occupied Battalion line by 2.30pm. Shelling ceased but rifle and M.G. fire remained accurate and constant, whenever a target presented itself, until dusk.” In the face of such a breakthrough it was decided, that evening, to withdraw to a more defensible line. Exhausted by their staunch defence the Battalion was withdrawn at 9.30pm and bivouacked on the west bank of the canal.

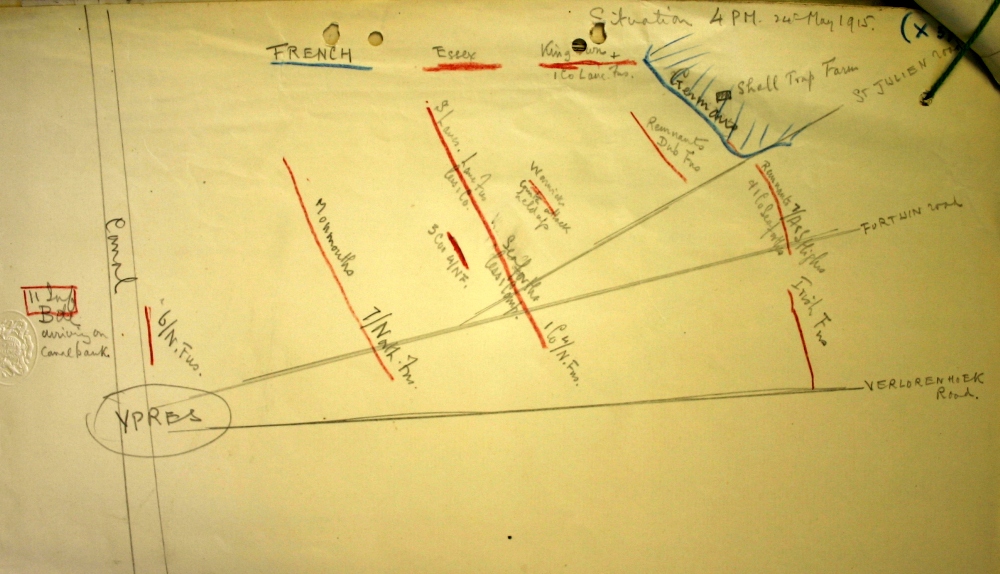

Sketch map showing situation at 4pm on 24 May 1915 after German gas attack. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diary (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

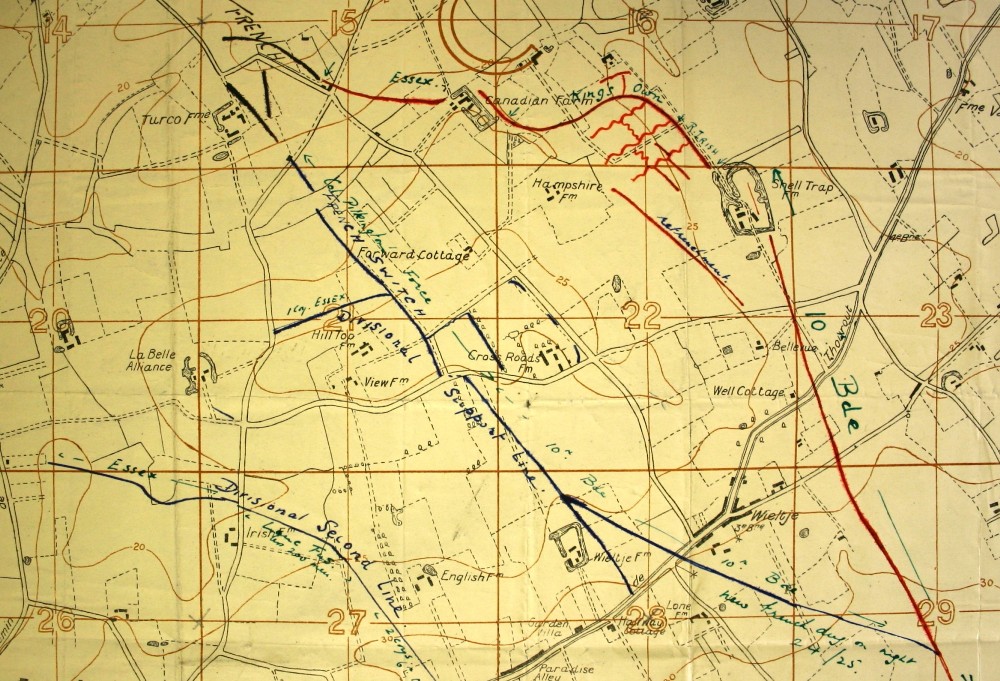

Trench map of positions around Shell Trap Farm. Red lines show the trench positions prior to the 24 May gas attack whilst the blue lines correspond to final positions after the attack. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diary (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

The cost

The War Diary records the Battalion strength in trenches on the morning of 24 May was 17 officers & 651 other ranks. Such had been the ferocity of the fighting, the shellfire, rifle and machine gun fire with the addition of the night-time chlorine gas attack that, when relieved, only one officer and 20 other ranks crossed the canal. What remained of the Battalion (reinforced by a draft) moved back to Vlamertinghe Chateau the following day. The entire Battalion strength was only 2 officers and 190 other ranks.

Leahy’s report concludes with these words:

“When the wounded were sent away after dark there were no Dublins in front of Battalion Headquarters. From about 2.30pm there was no fighting in our trenches. Everyone held onto them to the last. There was no surrender, no retirement and no quarter given or accepted. They all died fighting at their posts.”

Inspecting the shattered remnants of the battalion on 28 May, General Sir William Pulteney commanding III Corps commented how sad it was to see so few remaining and emphasised the fact that the Battalion should console itself with the knowledge that those who had gone had “Done their job”.

Astonishingly, the Battalion (at full strength 1027 officers and men) suffered just under 1,500 casualties in one calendar month from 24 April – 24 May 1915. This figure clearly includes reinforcements who made up earlier losses. Most of these casualties were sustained during three distinct period in the line. I have copied the relevant dates from the summary given in full below:

- 25 April: 7 officers killed, 8 wounded. Other ranks: 45 killed, 80 wounded, 371 missing

- 9-10 May: 4 officers killed, 3 wounded. Other ranks: 37 killed, 60 wounded, 185 missing

- 24 May: 9 officers killed, 1 wounded, 1 gassed, 1 missing, 1 POW. Other ranks: 14 killed, 35 wounded, 547 missing

For more information Thomas Stephen Burke’s ‘The 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers and the Tragedy of Mouse Trap Farm: April and May 1915’ is well worth a read. Shell Trap Farm (renamed Mouse Trap Farm) stayed in German hands from May 1915 until its capture at the start of the Passchendaele offensive on 31 July 1917.