Posts Tagged ‘Canford Cemetery’

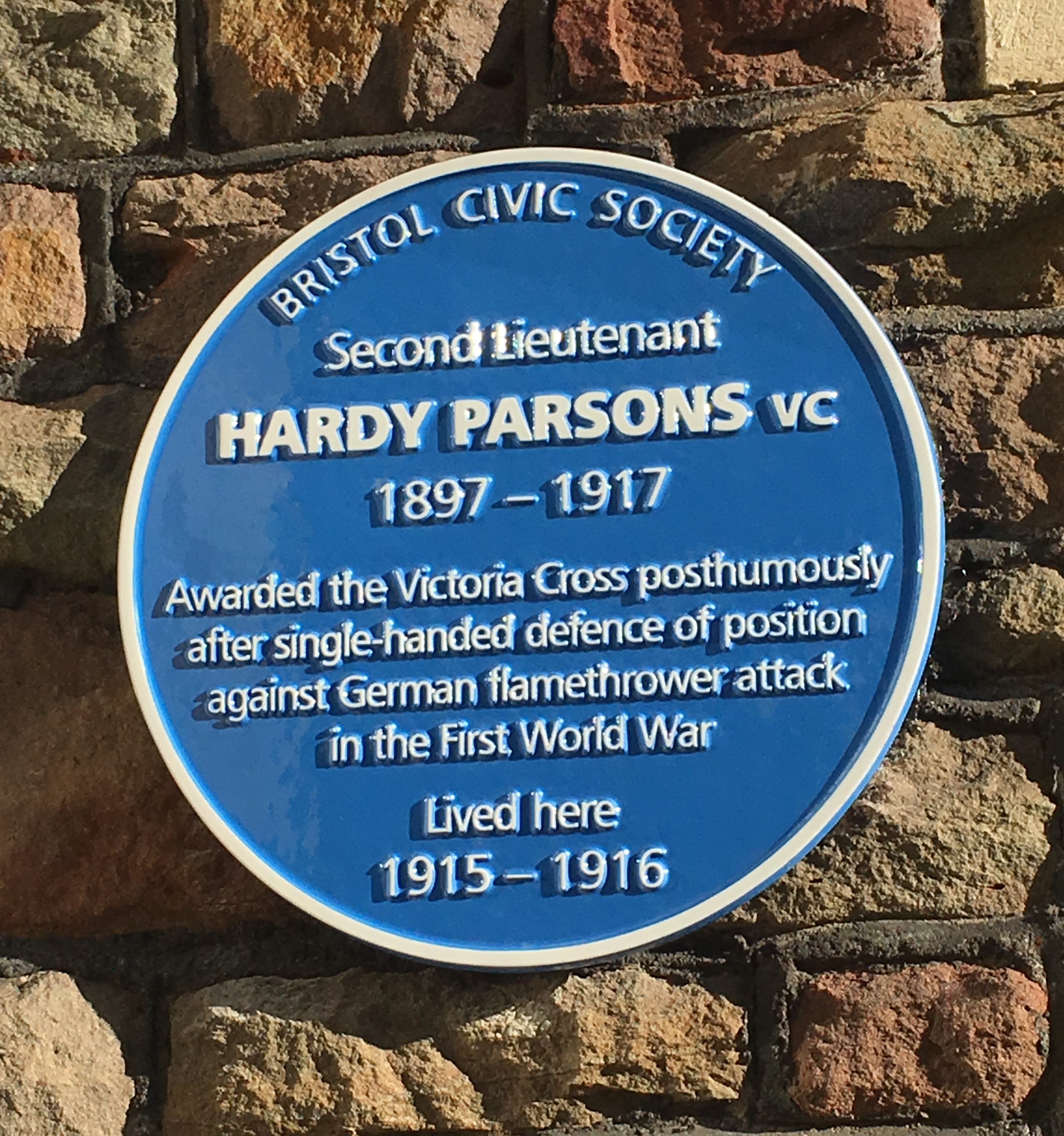

Blue plaque unveiled commemorating the life of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

Second Lieutenant Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. Image courtesy Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Ref GLRRM:04750.6

Today saw the unveiling of a Bristol Civic Society blue plaque at the former Bristol home of my local Victoria Cross recipient, 2/Lt Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Gloucestershire Regiment. He lived a fifteen minute walk from my house and I have known his story for the past fourteen years that I have lived in the city.

My colleague Clive Burlton and I were determined to see Hardy’s strong association with Bristol and the West Country recognised. As his Government funded VC commemorative stone was unveiled in Rishton, Lancashire back in August we have spent the last year working on honouring Hardy’s local connections with a Bristol Civic Society blue plaque.

The plaque was unveiled by the Archie Smith and Grace Tyrrell, Head Boy and Head Girl of Kingswood School along with the Lord Mayor of Bristol, Cllr Lesley Alexander. The ceremony was attended by members of the Bristol Civic Society; the former Gloucestershire Regiment; the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum; the Bristol University Officer Training Corps; Kingswood School, Bath, Redland Green School and Dolphin Schools in Bristol; bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles Regiment; members of the Western Front Association and the Bristol Great War network and representatives of the Kingswood Association, whose generous donation enabled the plaque to be made and installed. Also attending were the Deputy Lord-Lieutenant for the County and City of Bristol, Colonel Andrew Flint and the Dean of Bristol, the Very Rev Dr David Hoyle. In total, around 100 people were in attendance for the ceremony. Afterwards a sizeable number of us were invited back to the Artillery Grounds on Whiteladies Road for light refreshments as guests of Bristol University Officer Training Corps.

Images of the unveiling ceremony can found below, followed by the culmination of much detailed research into Hardy’s life by Clive Burlton and myself. I can only hope that the people of Bristol and Bath embrace his memory. He deserves that.

Blue plaque for Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at 54, Salisbury Road, Redland, Bristol

Clive Burlton gives the opening address

Jeremy Banning providing the historical background to the life of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

The Lord Mayor of Bristol with members of Bristol University Officer Training Corps and bandsmen from the Salamanca Band of the Rifles

A delighted Jeremy Banning and Clive Burlton with Hardy’s new blue plaque

The ceremony was well attended by the military

After the ceremony many of those attended were able to mingle and discuss Hardy’s life

Bristol 24/7 have also covered the story: https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/pictures-blue-plaque-revealed-wwi-soldier-redland/ as have BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-41918314. Our BBC Points West interview is available for a week from 16 minutes in here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b09bzw5f/points-west-evening-news-08112017

The life of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC, 14th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

Hardy Falconer Parsons was born on 30 June 1897 at Rishton, near Blackburn, Lancashire, the first of three boys. His father, the Rev James Ash Parsons, was a Wesleyan Minister whilst his mother Henrietta (known as Rita) was the daughter of a railway inspector from York. Hardy’s rather unusual middle name came from Rita – Falconer was her maiden name.

The Rev James Ash Parsons had spent eleven years in total in the slums of East London as superintendent of the Methodist Leysian Mission. Ill health forced him and Rita to St Anne’s on Sea, south of Blackpool and it was whilst living here that Hardy was born. There followed three years at Arnside immediately south of the Lake District. Clearly, the ethos of duty and service to others, so well practiced by his parents, was a huge part of Hardy’s upbringing.

Hardy’s first school was King Edward VII School at Lytham St Annes. From the paper work we have found it appears the family moved to Bristol in 1912 when the Rev James Ash Parsons became pastor at the Old King Street Wesleyan Chapel (sadly, now demolished). The family moved to 54 Salisbury Road in Redland and Hardy attended Kingswood School in Bath until April 1915.

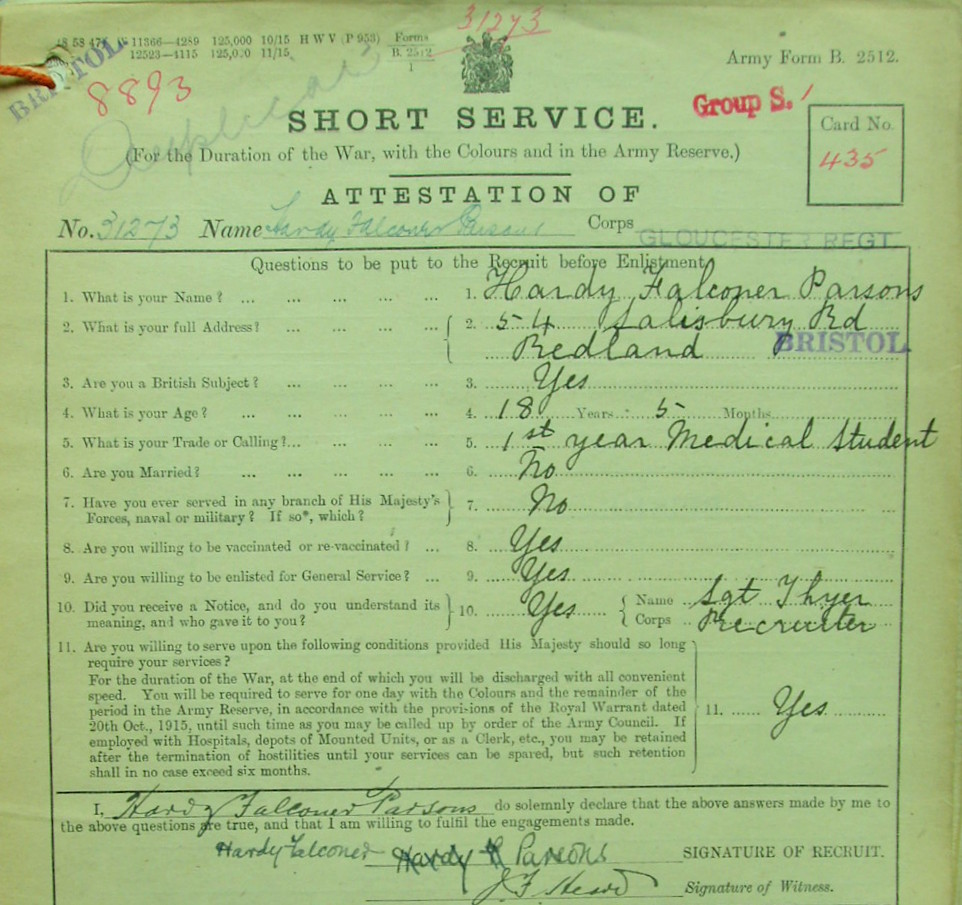

Extract from attestation papers of Hardy Falconer Parsons (National Archives: WO339/73298)

After school Hardy Parsons became a Medical Student at Bristol University with the aim of becoming a medical missionary. At the end of November 1915, during his first year at the University he signalled his wish to volunteer for service by attesting when aged just 18 years & 5 months but was immediately placed on the Army Reserve.

He had previously declined a safe post in a Government munitions laboratory, feeling that he ought not to withhold himself from the fullest sacrifice. He hated war, but recognised that the making of munitions was just as much war work as was the actual taking of life.

He joined the University’s Officer Training Corps in May 1916, a month shy of his 19th birthday, and then passed his first Bachelor of Medicine degree. His attestation papers make interesting reading – recording that he was a tall man, especially for that time, standing at 6ft ¾ inch tall. In early October 1916 he was posted to 6th Officer Cadet Battalion at Balliol College, Oxford and, on 25 January 1917, was appointed to the Gloucestershire Regiment as a Second Lieutenant.

He eventually joined the 14th Battalion in March, a unit which had previously been a ‘Bantam’ battalion – with men of 5ft 3 inches and less serving in its ranks. By the time the nearly 6ft 1 inch Hardy joined the battalion this unique distinction had been very much diluted. In February 1917 the battalion war diary records 475 ‘normal size men’ joining the battalion.

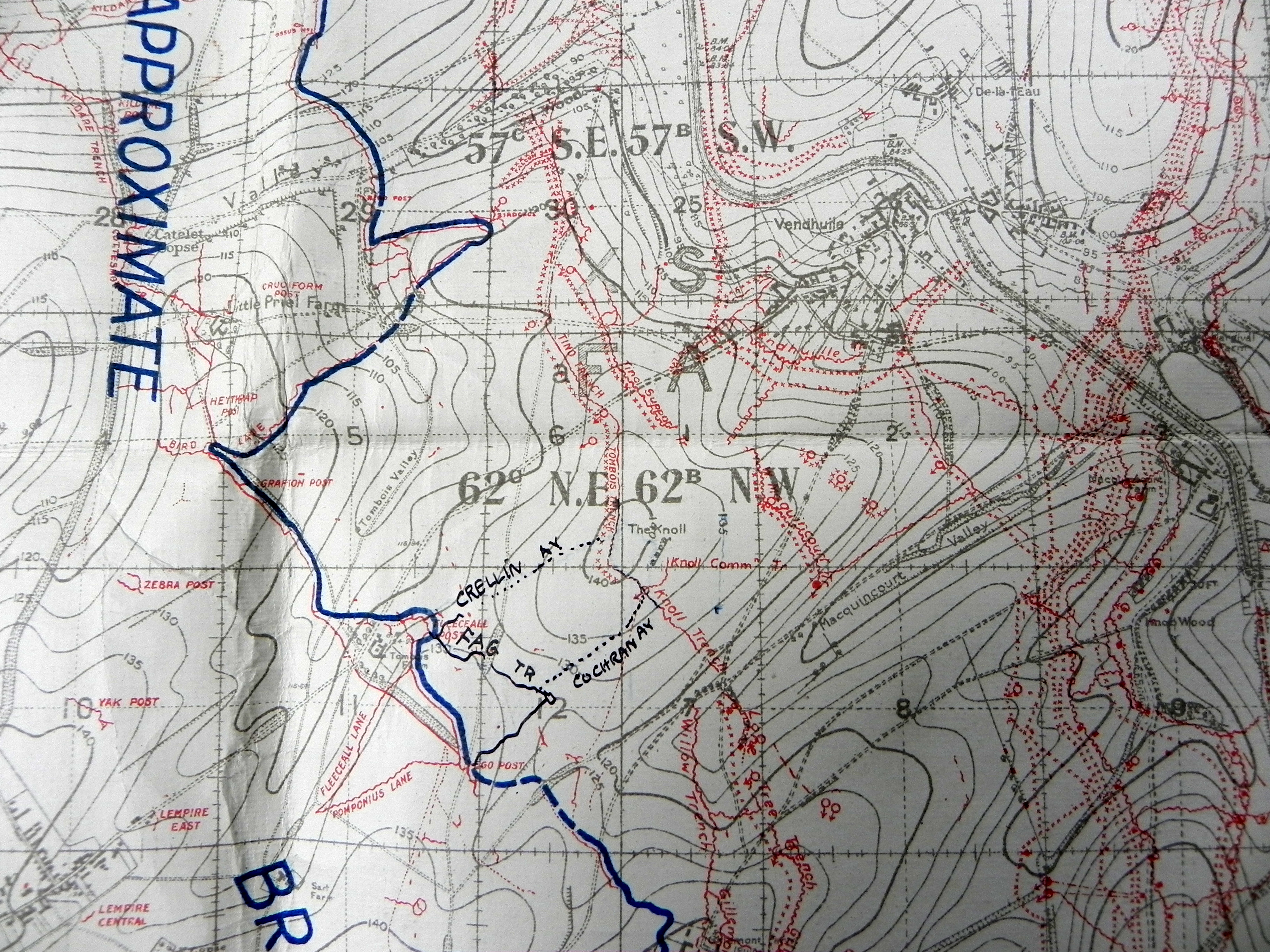

Trench map extract of The Knoll – captured by 105 Infantry Brigade on 19 August 1917

On 21 August 1917 near the village of Vendhuile in the eastern part of the Somme, Hardy’s battalion were holding recently captured trenches at a position known as The Knoll in the Hindenburg Line outpost zone. Their relief of the units who had captured the Knoll some two days before was completed by 1.30am that night.

Modern view of The Knoll, photographed October 2017. Vendhuile, the Hindenburg Line and St Quentin Canal are out of view in the valley.

It was a critical position which afforded observation over the Hindenburg Line and St Quentin canal a mile away – observation the British wanted and the Germans wanted to prevent. In fact, men from Bristol’s 1/4th and 1/6th Territorial battalions had fought for the same view in this same position four months previously.

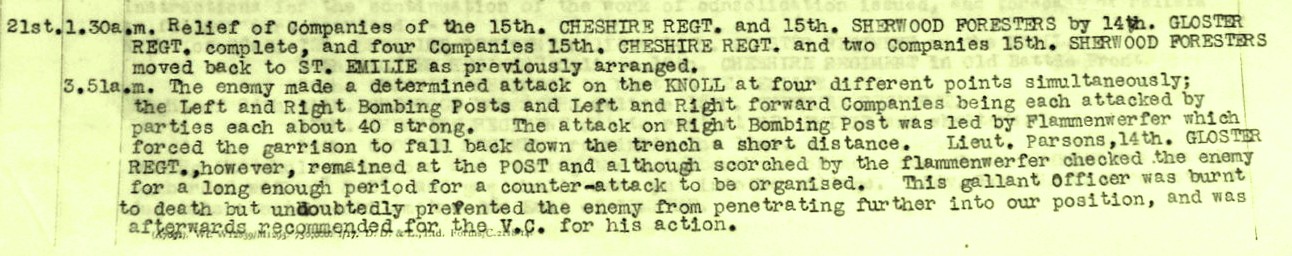

The loss of such critical terrain forced the Germans into a devastating counter-attack. As recorded in the Brigade war diary, at 3.51am the Germans struck. Militarily, it was a brilliantly executed counter-attack by the Germans – The Knoll being attacked at four points simultaneously. German infantry were accompanied by special detachments using portable flamethrowers. These forced Hardy Parsons’ men back. However, he alone stuck to his bombing post and held his position, throwing bombs (hand grenades) at approaching Germans until a British counter-attack could be launched. The counter-attack was successful – the Germans were repulsed from the trenches around The Knoll and within 40 minutes this bloody action was over. Much of this success is due to Hardy’s refusal to yield ground.

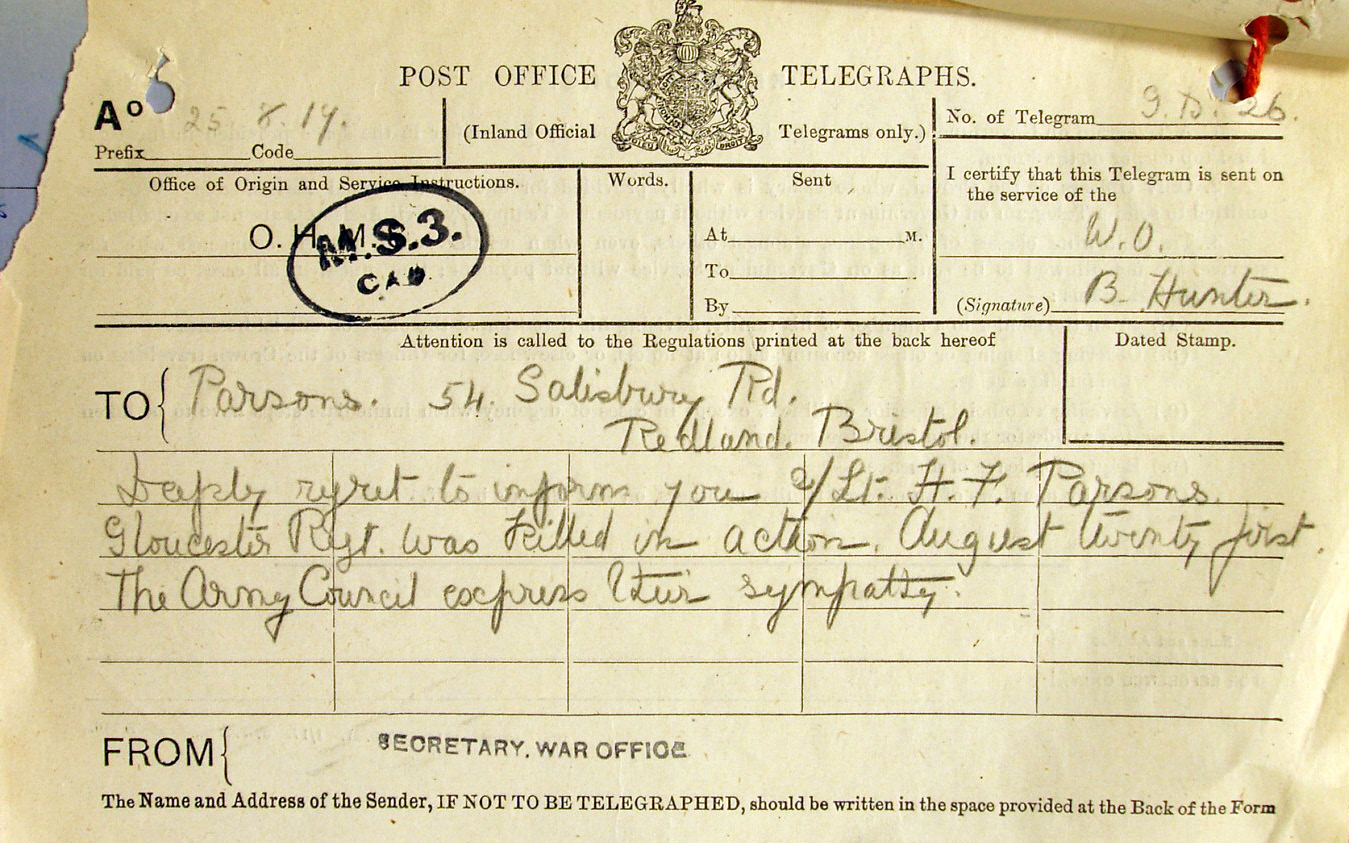

Telegram sent to the Rev James Ash Parsons informing him of Hardy’s death

During his heroic sole defence of The Knoll Hardy had been severely burnt by liquid fire. Writing these words over a hundred years later I cannot begin to imagine the sense of duty that compelled him to stay at his post, or the pain he would have endured during and after sustaining such horrific burns. Unsurprisingly, the nature of his wounds proved too severe and he succumbed later that day, dying at the age of just 20 years and two months. Hardy Falconer Parsons is buried in the immaculate CWGC cemetery at Villers-Faucon.

N.B. I was contacted in August 2019 by Dr Markus Schroeder whose great great uncle, Ernst Komander, served with the 2./Jäger 6, Jäger-Regiment 6, 195 Infanterie-Division. He tells me that regimental records show it was Jäger-Regiment 6 that led the attack on the 14th Gloucesters with the specialist flamethrowers employed by Sturmbataillon 3. Ernst Komander was wounded on the day of the attack and died of those wounds two days later. He is buried in Block 2, Grave 56 in Caudry German Military Cemetery.

Grave of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC at Villers Faucon Communal Cemetery

Hardy’s effects, consisting of just a wrist ID disc and two wrist watches were sent by registered post to his father within the month.

105 Infantry Brigade war diary describing the events of 21 August 1917

The Brigade diary describes Hardy’s gallantry, commenting that he ‘was afterwards recommended for the VC for his action’. During the war many acts of bravery were put forward for the VC but subsequently rejected. However, in Hardy’s case, approval was given. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross – personally presented to his father by King George V at a ceremony on Durdham Down (Bristol) on 8 November 1917. Hardy’s father also attended the Colston Hall event on 15 February 1919 when he was presented, on his dead son’s behalf, with an illuminated address and gold watch by Lord Mayor Twiggs. The address included Hardy’s full Victoria Cross citation:

“For most conspicuous bravery during a night attack by a strong party of the enemy on a bombing post held by his command. The bombers holding the block were forced back, but Second Lieutenant Parsons remained at his post, and, single-handed, and although severely scorched and burnt by liquid fire, he continued to hold up the enemy with bombs until severely wounded. This very gallant act of self-sacrifice and devotion to duty undoubtedly delayed the enemy long enough to allow the organisation of a bombing party, which succeeded in driving back the enemy before they could enter any portion of the trenches. This gallant officer succumbed to his wounds.”

Hardy Parsons was only the second member of the Gloucestershire Regiment to receive a VC during the First World War.

Hardy Falconer Parsons VC Chapel Memorial, Kingswood School, Bath

On 23 July 1923, a tablet in his memory was unveiled in the chapel of Kingswood School in Bath and his Victoria Cross and campaign medals are held by the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, having been presented to the Gloucestershire Regiment at a ceremony in 1970 in front of what is now City Hall, attended by the Lord Mayor, Cllr Bert Wilcox.

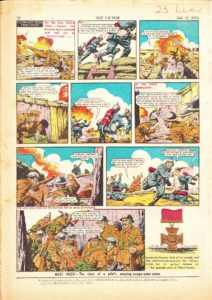

Victor comic, 11 July 1970 – the story of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

The collection also includes a portrait photograph of Hardy in uniform; the bronze memorial plaque sent, popularly known as the “Dead Man’s Penny” to his parents after the war and his Gloucestershire Regiment collar badge. Engraved on the back of the badge are the words “Irene Randall 10 Newfoundland St., Bristol 1917”. Who she was, and why he had that, we will probably never know….

Victor comic, 11 July 1970 – the story of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC

On 11 July 1970, the Victor Comic ran a cartoon story with 10 sketches on its front and back pages, recounting the story of the 14th Gloucesters action at The Knoll and to the deeds of Hardy Falconer Parsons – bringing his heroic actions to the attention of a younger audience.

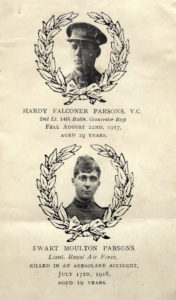

Ewart Moulton Parsons

And as for the Parsons family, despite Hardy’s death, the war had not finished with them. Hardy had two younger brothers; Ewart Moulton and Lyall Ash. Lyall was born too late to serve but Ewart, born the year after Hardy, was working as an apprentice engineer at Bristol company, Brecknell Munro and Rogers in summer 1916.

Page from memorial booklet for Hardy and Ewart Parsons

He joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and by 17 July 1918, was a 19 year old Lieutenant and pilot in No.50 Training Depot Station at Eastbourne, flying his Sopwith F1 Camel fighter high above the Seaplane Station. What happened next is still unclear but his plane went into a spin and plummeted to the ground from 3000ft. Unsurprisingly, Ewart was killed instantly.

Grave of Ewart Parsons in Canford Cemetery, Bristol

His body was brought back to Bristol and his funeral held at the Old King Street Wesleyan Chapel where his father was the pastor. The coffin was borne by six RAF officers and taken on a gun carriage to Canford Cemetery, where the internment took place followed by the sounding of the Last Post.

So, in the space of eleven months James Ash and Rita Parsons had lost two of their three boys. On the base of the stone cross marking Ewart’s grave at Canford Cemetery the family also commemorated his brother, Hardy. Like so many families across the world, the Parsons’ suffered grievously in the war.

Detail on Ewart Parsons’ grave in Canford Cemetery

But, as this research is primarily based on Hardy I would like to end with a description of him, provided by his father which, when considered alongside his Victoria Cross action, shows him to have been a truly remarkable young man, a perfect example of the loss of the best of that generation:

“Hardy lived all of his life from early childhood on the same high plane of self-forgetfulness and sacrifice in his thought for and service of others”

Hardy Falconer Parsons VC (30 June 1897 – 21 August 1917)

Sources of information consulted for this article include:

Service record of Hardy Falconer Parsons VC (National Archives: WO339/73298)

105 Infantry Brigade War Diary (National Archives: WO95/2486)

14 Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment War Diary (National Archives: WO95/2486)

RAF service record of Ewart Moulton Parsons

Census returns (1901 & 1911)

Material from the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum http://www.soldiersofglos.com/

Victor Comic, 11 July 1970

London Gazette – various dates

The Kingswood Magazine, Vol. XX, No.10, December 1917

North Devon Journal, 27 August 1931

North Devon Journal, 10 November 1949

Gliddon, Gerald, VCs of the First World War: Cambrai 1917, Stroud, 2004