Posts Tagged ‘Loos’

The 1st King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry at the Hohenzollern Redoubt

Introduction

Few places on the Western Front held such a reputation as the Hohenzollern Redoubt. Attacked by the 9th (Scottish) Division at the start of the Battle of Loos on 25 September, the redoubt, jutting out into No Man’s Land was fiercely defended. It is perhaps most well known as the scene of the disastrous 46th (North Midland) Division’s attack on 13 October 1915. The losses to the 46th Division of 3,763 officers and men that day are greater than sustained in their failed attack at Gommecourt on the First Day of the Somme on 1 July 1916. Following the failure of this attack the line stabilised and the Hohenzollern Redoubt soon developed into a vicious mining sector as tunnelling operations reduced the landscape to a sea of huge mine craters.

Modern map showing the Loos battlefield. Auchy-les-Mines can be seen south of the La Bassée canal. The Hohenzollern Redoubt was not far from the road passing Cité Magdagascar running to Vermelles.

The Battle of Loos

However, it is one event between the Scots’ initial attack and the 13 October endeavour that is the subject of this article. The Scots’ success in penetrating the German positions had been bought at a heavy price. Troops of the 26th Brigade had taken the Redoubt and pushed north to Fosse 8 and the Dump. German counter-attacks reversed these gain, pushing the Scots back to the eastern face of the Hohenzollern Redoubt by the end of following day. Severely depleted from their action, the Scots handed over their tenuous gains to the 28th Division, the positions being taken by units of the 85th Brigade.

Fierce fighting continued for the next three days with German counter-attacks slowly and painfully retaking trenches. At the end of 30 September the British occupied the West Face of the Redoubt and Big Willie Trench. The Germans controlled most of Little Willie Trench, threatening the north flank of the Redoubt. On the night of 30 September/1 October 84th Brigade relieved 85th Brigade. German observation of this relief from the heights of the Dump was total and the new British occupants were subjected immediately to strong bombing attacks. The British held on – but only just.

That night, they would attack to improve their hold on the German trenches. The plan was risky, involving no artillery bombardment. The attacking force captured parts of Little Willie Trench but could advance no further. German retaliation was swift; artillery subjected the Redoubt and Little Willie to regular and heavy trench mortar fire. A German bombing attack retook Little Willie Trench, followed by the loss of the Chord and West Face. Other than a small section of Big Willie Trench, the British were for the most part back in their original lines. The blood-soaked redoubt would have to be assaulted again.

The 1st King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry into the line

The 1st Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (83rd Brigade, 28th Division) had fought with great aplomb at Second Ypres. Prior to the Battle of Loos the battalion had been holding trenches on Messines Ridge. Their move south, via Bailleul and Outtersteene brought them to Noyelles les Vermelles on the afternoon of 27 September. The following afternoon they occupied reserve trenches on the Vermelles road as a bombardment was expected. After 90 minutes in position they returned to their billets in Noyelles.

On the morning of 29 September the Battalion moved forward. B & C Companies occupied Sussex Trench whilst Battalion HQ and the remainder of the unit stayed in the Lancashire lines. In the afternoon B & D moved up to the line, D Company in the firing line in BIG WILLIE trench with B Company in support. Later that afternoon, the remainder of the Battalion moved up to the reserve trenches.

Having taken twelve casualties the battalion were relieved the following day. They proceeded to the old British front line north of the Hulluch road, arriving there at 2.15am on 1 October. Three and a half hours later the Battalion were ordered to move up and occupy the old German buy real ambien online front line trenches. Later that day they were relieved by 2nd Highland Light Infantry and proceeded to billets at Annequin. On the morning of 3 October the Battalion marched to Vermelles and then into trenches opposite the redoubt to relieve the 6th Welsh (84th Brigade).

Trench map showing Hohenzollern Redoubt, The Dump and Fosse 8. British lines in blue, German lines in red.

Attack

That night the C.O., Lt-Colonel C.R.I. Brooke DSO and Major Mallinson DSO went to Brigade HQ. An attack was to be made at 4.45am on 4 October by three battalions; the 1st KOYLI and 2nd East Yorkshires would attack the redoubt frontally, leaving the 2nd King’s Own to capture and consolidate Big Willie Trench. The optimistic plan depended on darkness providing the assaulting parties with the necessary element of surprise. Even then, the British would be advancing into a tumbled maze of trenches. The assaulting troops had no idea what they would be facing; there had been no time to reconnoitre the position.

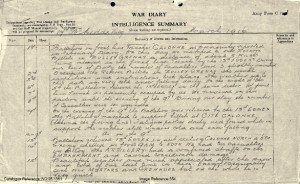

At 4.15am the first two waves of the 1st KOYLI were in position thirty yards in front of their trench. Fifteen minutes later a third wave followed. The 2nd East Yorkshires deployed similarly. Battalion war diaries mention a distinct lack of artillery fire. Whatever shelling there was had no discernible effect on the German trenches. The Battalion War Diary for 4 October records the attack thus:

A & D Coys ordered to attack HOHENZOLLERN REDOUBT

4.45am – A & D attacked and were met with very heavy machine gun and rifle fire. There was no artillery bombardment. The distance to the German line was about 200 yards and the men got half way across. By then they were practically wiped out.

These few lines make grimly predictable reading. Traversing 200 yards of open ground swept by machine-gun fire proved impossible. The war diary records the following casualties:

2/Lt A.H. Martindale 1st KOYLI killed

2/Lt C.L. Pearson 1st KOYLI wounded

2/Lt F.W. Graham 4th DLI, attached 1st KOYLI missing

2/Lt P.J.C. Simpson 3rd KOYLI, attached 1st KOYLI missing

Other Ranks – killed 10, wounded 65, missing 101

It concludes by noting ‘There is no doubt that most of the missing were killed. A few wounded were got in during the night 4th/5th.’ Losses to the East Yorkshires and 2nd King’s Own were equally heavy. The attack stood no chance of success. Following their mauling the Battalion were relieved by the 1st Coldstream Guards the next day. This move signalled the relief of the 28th Division by the Guards Division. In a week the Division had suffered over 3,200 casualties. There is no after action report in the 1st KOYLI diary but the summary given by Lt-Colonel Blake, 2nd East Yorkshires whose men attacked alongside the 1st KOYLI is damning, attributing the failure of the attack to the following causes:

(i) No Artillery bombardment

(ii) Complete lack of element of surprise. The Germans were well prepared, and had not been in the slightest shaken by the desultory shelling that had taken place throughout the day.

(iii) The Germans had been digging in during the day previous, and had thoroughly improved their trenches.

(iv) The relief the day before did not finish until 7pm. Company officers had only very indistinct idea of the trenches they were occupying, and none at all of the positions they were to attack.

So, when next at Vermelles, Auchy and the site of the Hohenzollern Redoubt give some thought not only to the Scots who attacked on 25 September 1915 and the North Midlanders (with two divisional memorials – one at Vermelles and one close to the redoubt) who fell is such number on 13 October but also to the men of the neglected 28th Division.

Following their exploits at Loos the 28th Division was moved to the Salonika front, sailing from Marseilles on 26 October 1915. Recommended reading includes Andrew Rawson’s ‘Loos 1915: The Northern Battle and Hohenzollern Redoubt (Battleground Europe)’

In memory of 21865 Private George William Williams, 1st KOYLI. Killed 4 October 1915, buried Arras Road Cemetery, Roclincourt.

The internet is a wonderful thing; for anyone interested in a certain battalion or unit it is now possible to hammer a few key words into a search engine and find all sorts of information about their part in major, set-piece battles. Forums and discussion groups also have their place. Some regimental museums have even transcribed all of their battalion war diaries, making them available online for free.

Extract from the 17th Middlesex Regiment War Diary. Reproduced with permission of National Archives, Ref: WO95/1361

Libraries, regimental archives and the National Archives all have information available to help understand events. However, what of the vast majority of time spent not going ‘over the top’ or taking part in the next ‘Big Push’? What of the less-well chronicled, monotonous but necessary routine of trench warfare?

It can be an immensely satisfying task to follow a unit’s movements around the battlefield; this is often undertaken as part of a family pilgrimage or greater desire to ‘follow in the footsteps’ of a relative who served. For me, when battlefield guiding, it is the part of the job that I love the most. Don’t get me wrong – I enjoy a general tour around the main tourist sites as well as the next person but it is in analysing the minutiae of war diary entries and working out such mundane things as billeting arrangements or where sports events were held that yields most fulfilment.

I recently returned from a bespoke trip following the 17th Middlesex Regiment (Footballers’ Battalion) around various villages and towns in French Flanders and the Gohelle coalfields in which they spent November 1915 – March 1916. My client’s grandfather had enlisted underage and spent four months with the battalion before being wounded in mid-March 1916; a wound which saved him from taking part in the Battalion’s action at Deville Wood on the Somme. During the four month period the Battalion held trenches at Cambrin, Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée and Festubert before taking over the Calonne sector from the French at the end of February.

Private James MacDonald, 17th Middlesex – first casualty of the battalion at Cambrin Churchyard Extension

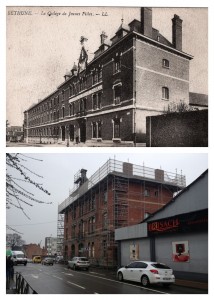

Over the course of our three day trip we visited all of these places, as well as many not associated with the 17th Middlesex; Fromelles, Aubers, Hulluch and Loos. Our stops were not solely restricted to places but included visits to 17th Middlesex Regiment men who had been killed in action. To stand at the grave of Donald Stewart (who served under the alias of Private James MacDonald) in Cambrin Churchyard Extension and know he was the first man of the battalion to be killed in action struck a particular chord. However, for me the highlight came during our visit to Béthune. The Battalion war diary for 2 December records a move to Béthune and billeting in the College des Jeune Filles. I had an old postcard of the college and knew the greater part of it still stood so arranged to visit it during our lunch stop.

Battlefield guides will recognise the satisfying feeling – being able to tell someone that their relative was at that spot on a certain date, not nearby or somewhere in the town but here, actually here. We had the same feeling eating our lunch of ham and cheese baguettes in the square at nearby want to buy ambien online Beuvry. A poorly-attended market filled half of the square but, as we sat eating, I was able to explain that this village, now almost a suburb of Bethune was where the Footballers’ Battalion had spent Christmas Day 1915. There was no plaque commemorating this event, no visible link at all, just the knowledge that men of the Battalion would have walked around the square over the festive time, amongst them my client’s grandfather. It made the lunch, eaten in the car whilst a steady drizzle fell that bit more special.

After a tour around the Loos battlefield I took my client to the site of Middlesex and Football Trench in the Calonne North sub-sector. It was here in that his grandfather was wounded in March 1916. The war diary of the 16th records ‘4 casualties occurred from GRENADES, 2 in “B” Coy and 2 in “D” Coy’; it is likely that my client’s grandfather was one of those wounded men as he left France on the 18th, crossing the channel for treatment at a hospital in Britain. Such were the effect of the wounds received that he was discharged from service three months later. Compared to many who served, his war was unremarkable – his service record shows he played no part in any major offensive and yet the four months he spent with the 17th Middlesex from November 1915 – March 1916 had a profound effect on him for the rest of his life.

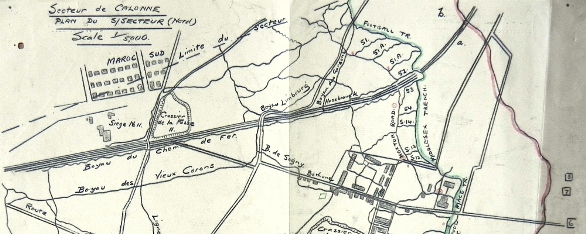

Map of Calonne North Sector showing Football and Middlesex Trenches . Reproduced from 6th Infantry Brigade War Diary held at National Archives, Ref: WO95/1353

Calonne North map overlaid on to Google Earth. Football Trench runs between the A21 motorway and the Lens – Bethune railway embankment.

Football Trench ran through what is now an open field next to the A21 motorway and the urban sprawl of miners’ cottages of Liévin. The railway line from Lens to Bethune runs across the northern tip of Middlesex Trench. Much of the rest of it is hidden under a civilian cemetery or is being built upon for new housing. A casual visitor to the site today would find it far from enchanting. Locals stared at our car with British number plates; clearly, the back streets of Liévin didn’t see too many battlefield tourists. However, the relative inaccessibility of the spot made visiting it that bit more special. To those of us in the car, it felt as though we had tracked down a site rather than merely followed the tourist signs. Having researched the young Middlesex soldier it certainly had an effect on me. It was a real pleasure to be able to share these places with his grandson; not just the obvious sites of front line and communication trenches but the places in he was billeted, the towns and villages he would have known well and the roads he marched along on his route to and from the front. To me, this is what makes following in a soldiers footsteps such an enriching experience.

N.B. A very readable account of the 17th Middlesex Regiment is Andrew Riddoch & John Kemp’s ‘When the Whistle Blows: The Story of the Footballers’ Battalion in the Great War’ – highly recommended.