Archive for 2015

Cycling tour to the Somme and Arras battlefields

Last weekend I had the pleasure of guiding nine gentlemen around the Somme and Arras battlefield on bikes. As a keen cyclist I try and take my bike when visiting the battlefields but this was something different in that it was the first organised specialist cycling trip I had put together.

Our base was the delightfully comfortable Les clés des places in the heart of Arras. The Somme was our destination on Friday, leaving the neglected battlefields of Arras for the Saturday.

Day One – The Somme

Friday morning dawned with beautiful weather. With the bikes fixed to the cars we headed south, crossing the ground voluntarily given up by the Germans as they pulled back to the Hindenburg Line in 1917. Parking at Serre Road Cemetery No.2, we got the bikes ready and headed off.

I had sent our proposed route to the group beforehand so everyone was aware of the distances involved. After an introduction of the battle and practices of the CWGC at Serre Road No. 2 we headed across Redan Ridge with its isolated ribbon of battlefield cemeteries to the small village of Beaumont Hamel. As one of the Somme’s most well visited sites with a highly evocative story the Sunken Lane offered our first chance to get to grips with the actions of July and November 1916. After hearing a 1st Lancashire Fusiliers officer, Lt E.W. Sheppard’s description of the 1 July attack we rode via Auchonvillers to Newfoundland Memorial Park where we had a good walk around the trench system, visiting all three cemeteries. The descent to Hamel was fun; infinitely more so than the climb up the Mill Road to the Ulster Tower! One of the group had previously served in the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment so I was able to show him the Pope’s Nose and discuss the 1/5th Battalion’s attempt to capture the position in September 1916.

After a visit to Lutyen’s imposing Thiepval Memorial and our first (and only) puncture of the day we headed via Mash Valley for lunch at the Old Blighty Tea Room in La Boisselle. Subsequent stops included the Lochnagar mine crater, Becourt, Fricourt and Mametz.

From the bottom of Dantzig Alley Cemetery we surveyed the undulating ground in front of us, a familiar view to the British in July 1916. Dominating the landscape is Mametz Wood, scene of so much heartache and horror for the 17th (Northern) and 38th (Welsh) Divisions. Our tour continued up to Montauban and Trônes Wood before a stop at Guillemont Road Cemetery where we paid our respects at the grave of Raymond Asquith, 3rd Grenadier Guards.

Raymond, the son of the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith has been described as ‘one of the most intellectually distinguished young men of his day’. He had been mortally wounded at the start of the Guards’ attack on 15 September 1916 and died on his way to a dressing station.

One of our group was a former Coldstream Guards officer and so we deviated from the original plan, heading to the Guards Memorial between Ginchy and Lesboeufs. The exposed position on the ridge to Lesboeufs is in the centre of the ground over which the Division fought in the second half of September 1916.

Postwar image of Guards Cemetery, Lesboeufs. The contrast between the haphazard crosses in this postcard and the neat rows of Portland headstones that greet the modern visitor is testament to the skill and dedication of the CWGC.

Our route back across the battlefield took in Delville Wood, looking a perfect picture of peace in dappled sunlight – the polar opposite of summer 1916.

Next up was High Wood where I described the ferocious fighting that had raged there through the high summer of 1916. The wood and Switch Line proved such a bulwark to advance that British efforts resorted to siege warfare techniques; employing Vincent and Livens Large Gallery Flame Projectors in the wood along with the use of tunnellers to plant a mine under German positions. In the late afternoon light of a perfect spring day it was hard to imagine the carnage in these quiet mellow fields and woods.

Crossing the Roman road we headed via Courcelette to Miraumont, along the Ancre valley to Beaucourt before a gentle climb up past Ten Tree Alley en route back to the cars. The conversations that night over a much-needed dinner and drinks all touched on the benefits of cycling in helping everyone’s appreciation of the battlefield.

View this route on plotaroute.com

Day Two – Arras

We awoke the next morning with slightly aching legs and for some, aching heads. There was no need for cars as we would be setting out directly from our hotel. Whilst the touristy spots of the Somme were packed with coaches and school groups the empty fields around Arras are a very different proposition. I assured our travellers that other than farmers and locals we would have the Arras battlefield to ourselves. Heading south via Beaurains (a bike path runs alongside the road for much of this) and London Cemetery we rode to Neuville-Vitasse, a village which in April 1917 was wired into the German defences with the main Hindenburg Line running just behind it.

Heading up the bumpy track to Neuville-Vitasse Road Cemetery was fun. From its dominating position I spoke of the 30th Division’s attack on 9 April 1917, the start of the Arras battle. The closely packed graves of the cemetery are predominantly made up of men from the 2nd Wiltshires and 18th King’s (Liverpool Regiment) who suffered grievous losses attacking across this ground.

I explained the connection with Hugh Dennis’s grandfather, Godfrey Hinnels, whom I had researched for the television programme, ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ Godfrey’s unit, the 1/4th Suffolk Regiment were tasked with salvage and burial duties in the days after the main attack. As such, it was likely he had been involved with the burial of the men that now lay in the cemetery’s walls.

Next up was Cojeul British Cemetery which is the resting place, amongst others, for two Victoria Cross recipients – Horace Waller, 10th KOYLI and Arthur Henderson, 2nd Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders.

Climbing Henin Hill we visited the remaining German pillbox (MEBU) before our next stop, the isolated and beautiful Cuckoo Passage Cemetery. This small battlefield cemetery, full of Manchester Regiment killed on 23 April 1917 lies at the limit of the Manchesters’ advance. I read aloud an account by Private Paddy Kennedy who served with the 18th Battalion describing events that buy mexican xanax day. Many of his comrades lay around us within the cemetery walls.

We returned back towards Heninel before picking the road up to Chérisy where I discussed the terrible events of 3 May 1917, the Third Battle of the Scarpe. Described by Cyril Falls in the Official History as ‘a melancholy episode’ the attack that day was an unmitigated disaster for the attacking British forces. British dead for the day reached nearly 6,000 for very little material gain.

Why cycling the battlefields is best…

Travelling by bike is by far the best way to appreciate the landscape; you feel every rise, every dip, every change in gradient. What would be a simple drive in a car takes on more meaning when on two wheels. Your thoughts turn irrevocably to the men whose footsteps still echo through the ground as, stealing a line from Sassoon, ‘they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack’.

Continuing towards Hendecourt our focus changed for a short time as I described the Canadian successes of August and September 1918. Stopping at Sun Valley Cemetery I pointed out the formidable obstacles of Upton Wood and The Crow’s Nest (the latter captured with great daring by the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) on the morning of 1 September 1918). Passing Quebec Cemetery we dropped down for our picnic lunch at the idyllic Valley Cemetery between Vis-en-Artois and Chérisy. This spot is the final resting place of a number of highly decorated officers and NCOs of the 3rd Battalion, Canadian Infantry who were killed nearby at the end of August 1918. Amongst the 3rd Battalion men buried here is the 23 year old Lieutenant Edward Slattery, DCM, MM & 2 Bars. From the decorations received whilst serving in the ranks and his tender age he appears to have been quite some soldier.

Suitably refreshed we headed back towards Guémappe and across the Route National towards Monchy-le-Preux. The road was blocked in the village, the result of a recent building collapse. Undeterred, we headed west where I explained about the village’s capture and the terrible loss of British cavalry in its narrow streets on 11 April 1917.

Having visited the impressive 37th English Division memorial and the Newfoundland Caribou in the village we rode eastwards, up Infantry Hill where I was able to regale the party with the story of the ‘Men who saved Monchy’: the disastrous 14 April 1917 assault by the Newfoundlanders and 1st Essex Regiment.

Infantry Hill is a special spot for me, the scene of so much concentrated fighting and yet, like so much of the Arras battlefield, it remains rarely visited. It was in these fields on 3 May 1917, that disastrous date for the British Army, that one of our group’s great uncles, Private Thomas Clark, 8th East Yorkshire Regiment was killed. Standing close to the spot where the 8th East Yorkshires went over the top I was able to explain the actions that day, reading from the war diary to enable everyone to appreciate the disaster that befell the attacking British troops and the magnificent defensive performance of the German forces.

Extract from the 8th East Yorkshire Regiment after-action report for 3 May 1917 action on Infantry Hill, east of Monchy-le-Preux

The Battalion moved forward at Zero hour [3.45am] but owing to the heavy smoke combined with the darkness they found it difficult to move on any definite point or points.

A platoon commander of the right-hand leading company found himself advancing up a small ridge which is to the south of the copse in O8 Central where he ran up against machine-gun fire. He was joined by a KSLI officer and some men. They moved forward together, the KSLI officer was killed as well as a number of men and as the place was bristling with machine guns and the copse occupied by snipers he stayed down in shell holes, returning at night to HILL TRENCH with 11 men on receipt of orders to do so from Battalion HQ…

…The men were in good heart and moved forward readily. I attribute the results to the heavy smoke, combined with the darkness which prevented people locating their points of direction. In addition to this the enemy barrage was very heavy to which must be added the very effective use of machine-gun both from the front but also enfilading attacking troops.

Casualties: 35 killed, 161 wounded, 39 missing

After some time to contemplate we returned to the village before riding down the Scarpe Valley to Fampoux where we looked at its capture on 9 April 1917 by the 2nd Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. Next up was another special spot; the Seaforth Highlanders cross overlooking the Hyderabad Redoubt, Greenland Hill and Roeux. Whilst there I explained the disastrous 11 April 1917 attack and read aloud the wonderful description left by Seaforth Highlander Private James Stout of events that day.

It is a great shame there is nothing at the former site of the Chemical Works, so bitterly fought over during the battle to show the ferocity of fighting and losses sustained to secure its possession. The site is now a Carrefour mini supermarket where we bought a cool drink and snacks before our ride via Athies back into Arras.

Our final stop of the day was the Arras Memorial where Private Thomas Clark and a further 34,765 men are commemorated. One of the group found the grave of his great uncle in the adjoining Faubourg D’amiens Cemetery. Tired but satisfied at the ground we had covered we headed back to the hotel before a good evening meal and much chat.

View this route on plotaroute.com

Day Three – A quick look north of Arras and back to Blighty

Our final day was overcast and rainy. Bikes were attached to cars before we visited the huge German cemetery at Neuville St-Vaast and French cemetery at La Targette. Next up was the preserved battlefield on Vimy Ridge before our final stop at Walter Allward’s masterpiece, the Vimy Memorial atop Hill 145.

My thanks to the wonderful group who I accompanied and for their generosity and looking after me so well.

If you are interested in a battlefield tour by bike, either as a group or by yourself then please get in touch via the Contact Page. I would be happy to put an itinerary together for any British battlefield and am happy to cycle up to 50 miles/day. However, there is so much to see that 25-40 miles/day is the ideal distance.

Introduction

Few places on the Western Front held such a reputation as the Hohenzollern Redoubt. Attacked by the 9th (Scottish) Division at the start of the Battle of Loos on 25 September, the redoubt, jutting out into No Man’s Land was fiercely defended. It is perhaps most well known as the scene of the disastrous 46th (North Midland) Division’s attack on 13 October 1915. The losses to the 46th Division of 3,763 officers and men that day are greater than sustained in their failed attack at Gommecourt on the First Day of the Somme on 1 July 1916. Following the failure of this attack the line stabilised and the Hohenzollern Redoubt soon developed into a vicious mining sector as tunnelling operations reduced the landscape to a sea of huge mine craters.

Modern map showing the Loos battlefield. Auchy-les-Mines can be seen south of the La Bassée canal. The Hohenzollern Redoubt was not far from the road passing Cité Magdagascar running to Vermelles.

The Battle of Loos

However, it is one event between the Scots’ initial attack and the 13 October endeavour that is the subject of this article. The Scots’ success in penetrating the German positions had been bought at a heavy price. Troops of the 26th Brigade had taken the Redoubt and pushed north to Fosse 8 and the Dump. German counter-attacks reversed these gain, pushing the Scots back to the eastern face of the Hohenzollern Redoubt by the end of following day. Severely depleted from their action, the Scots handed over their tenuous gains to the 28th Division, the positions being taken by units of the 85th Brigade.

Fierce fighting continued for the next three days with German counter-attacks slowly and painfully retaking trenches. At the end of 30 September the British occupied the West Face of the Redoubt and Big Willie Trench. The Germans controlled most of Little Willie Trench, threatening the north flank of the Redoubt. On the night of 30 September/1 October 84th Brigade relieved 85th Brigade. German observation of this relief from the heights of the Dump was total and the new British occupants were subjected immediately to strong bombing attacks. The British held on – but only just.

That night, they would attack to improve their hold on the German trenches. The plan was risky, involving no artillery bombardment. The attacking force captured parts of Little Willie Trench but could advance no further. German retaliation was swift; artillery subjected the Redoubt and Little Willie to regular and heavy trench mortar fire. A German bombing attack retook Little Willie Trench, followed by the loss of the Chord and West Face. Other than a small section of Big Willie Trench, the British were for the most part back in their original lines. The blood-soaked redoubt would have to be assaulted again.

The 1st King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry into the line

The 1st Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (83rd Brigade, 28th Division) had fought with great aplomb at Second Ypres. Prior to the Battle of Loos the battalion had been holding trenches on Messines Ridge. Their move south, via Bailleul and Outtersteene brought them to Noyelles les Vermelles on the afternoon of 27 September. The following afternoon they occupied reserve trenches on the Vermelles road as a bombardment was expected. After 90 minutes in position they returned to their billets in Noyelles.

On the morning of 29 September the Battalion moved forward. B & C Companies occupied Sussex Trench whilst Battalion HQ and the remainder of the unit stayed in the Lancashire lines. In the afternoon B & D moved up to the line, D Company in the firing line in BIG WILLIE trench with B Company in support. Later that afternoon, the remainder of the Battalion moved up to the reserve trenches.

Having taken twelve casualties the battalion were relieved the following day. They proceeded to the old British front line north of the Hulluch road, arriving there at 2.15am on 1 October. Three and a half hours later the Battalion were ordered to move up and occupy the old German buy real ambien online front line trenches. Later that day they were relieved by 2nd Highland Light Infantry and proceeded to billets at Annequin. On the morning of 3 October the Battalion marched to Vermelles and then into trenches opposite the redoubt to relieve the 6th Welsh (84th Brigade).

Trench map showing Hohenzollern Redoubt, The Dump and Fosse 8. British lines in blue, German lines in red.

Attack

That night the C.O., Lt-Colonel C.R.I. Brooke DSO and Major Mallinson DSO went to Brigade HQ. An attack was to be made at 4.45am on 4 October by three battalions; the 1st KOYLI and 2nd East Yorkshires would attack the redoubt frontally, leaving the 2nd King’s Own to capture and consolidate Big Willie Trench. The optimistic plan depended on darkness providing the assaulting parties with the necessary element of surprise. Even then, the British would be advancing into a tumbled maze of trenches. The assaulting troops had no idea what they would be facing; there had been no time to reconnoitre the position.

At 4.15am the first two waves of the 1st KOYLI were in position thirty yards in front of their trench. Fifteen minutes later a third wave followed. The 2nd East Yorkshires deployed similarly. Battalion war diaries mention a distinct lack of artillery fire. Whatever shelling there was had no discernible effect on the German trenches. The Battalion War Diary for 4 October records the attack thus:

A & D Coys ordered to attack HOHENZOLLERN REDOUBT

4.45am – A & D attacked and were met with very heavy machine gun and rifle fire. There was no artillery bombardment. The distance to the German line was about 200 yards and the men got half way across. By then they were practically wiped out.

These few lines make grimly predictable reading. Traversing 200 yards of open ground swept by machine-gun fire proved impossible. The war diary records the following casualties:

2/Lt A.H. Martindale 1st KOYLI killed

2/Lt C.L. Pearson 1st KOYLI wounded

2/Lt F.W. Graham 4th DLI, attached 1st KOYLI missing

2/Lt P.J.C. Simpson 3rd KOYLI, attached 1st KOYLI missing

Other Ranks – killed 10, wounded 65, missing 101

It concludes by noting ‘There is no doubt that most of the missing were killed. A few wounded were got in during the night 4th/5th.’ Losses to the East Yorkshires and 2nd King’s Own were equally heavy. The attack stood no chance of success. Following their mauling the Battalion were relieved by the 1st Coldstream Guards the next day. This move signalled the relief of the 28th Division by the Guards Division. In a week the Division had suffered over 3,200 casualties. There is no after action report in the 1st KOYLI diary but the summary given by Lt-Colonel Blake, 2nd East Yorkshires whose men attacked alongside the 1st KOYLI is damning, attributing the failure of the attack to the following causes:

(i) No Artillery bombardment

(ii) Complete lack of element of surprise. The Germans were well prepared, and had not been in the slightest shaken by the desultory shelling that had taken place throughout the day.

(iii) The Germans had been digging in during the day previous, and had thoroughly improved their trenches.

(iv) The relief the day before did not finish until 7pm. Company officers had only very indistinct idea of the trenches they were occupying, and none at all of the positions they were to attack.

So, when next at Vermelles, Auchy and the site of the Hohenzollern Redoubt give some thought not only to the Scots who attacked on 25 September 1915 and the North Midlanders (with two divisional memorials – one at Vermelles and one close to the redoubt) who fell is such number on 13 October but also to the men of the neglected 28th Division.

Following their exploits at Loos the 28th Division was moved to the Salonika front, sailing from Marseilles on 26 October 1915. Recommended reading includes Andrew Rawson’s ‘Loos 1915: The Northern Battle and Hohenzollern Redoubt (Battleground Europe)’

In memory of 21865 Private George William Williams, 1st KOYLI. Killed 4 October 1915, buried Arras Road Cemetery, Roclincourt.

This brief article will look at the actions and casualties sustained by the 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers (part of 10th Brigade, 4th Division) during the Second Battle of Ypres. One often feel when visiting the Ypres Salient that the sheer horror of the Third Battle (Passchendaele), fought during the summer and autumn of 1917, can overshadow earlier clashes. Many first-time visitors may be unaware of the horrendous casualties sustained by the British in earlier desperate defensive battles (First Ypres – Oct-Nov 1914) and Second Ypres (April-May 1915). The latter battle saw the advent of chemical warfare when the Germans released chlorine gas on a four mile frontage in the late afternoon of 22 April against two French divisions defending the north of the salient. Gas also drifted across Canadian positions holding the left flank of the British. The initial success of this experimental weapon, which left a trail of dead and dying in its wake, enabled the Germans to advance from the fields around Poelcapelle and Langemarck to Steenstraat on the Yser Canal. The stalwart defence of the untried 1st Canadian Division (my grandfather, a private in the 13th Battalion CEF, amongst them) and the rushing forward of British troops to plug the gap around Ypres is not the subject of this article. However, this defence must be appreciated to put the specific story of the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers into context. Not surprisingly, considering their initial success, the Germans used gas on a number of other occasions during the battle, culminating in the Battle of Bellewaarde Ridge on 24-25 May. A terrifically detailed description of the opening phase of Second Ypres can be found here: http://www.greatwar.co.uk/battles/second-ypres-1915/index.htm.

Into action

On 23 April 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers were told to stand by and be prepared to move at a half hours notice. The following day they marched via Vlamertinghe to the outskirts of Ypres and at midnight to St Jean where they deployed west of the Wieltje – St Jean road at 4am. The Battalion War Diary records they suffered heavy casualties digging in on a line a quarter of a mile from and facing St Julien. There follows a ‘quiet morning up to 11am’ until the Northumbrian Infantry Brigade attacked through their trenches. During this period Captain Banks was killed, his command being assumed by Captain Basil Maclear. The War Diary records ‘heavy shelling throughout the day, and intermittent musketry’. There follows a few days of relative quiet which is shattered on 2 May when, in a foretaste of future action, the enemy attacked under cover of gas. Men of the left hand company were most affected but the German attack failed to reach the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers trenches.

After relief on 4 May the Battalion bivouacked on the east bank of the Yser Canal, a half mile north west of La Brique. This period away from the front line was shortlived as the Germans made a concerted effort to break the British line. This attack, made against the 27th and 28th Divisions on 8 May, began what was named by the post-war Battles Nomenclature Committee, the Battle of Frezenberg Ridge. A violent German artillery bombardment caused terrible destruction to the British defences. Whilst avoiding this initial bombardment the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers were warned at noon to be prepared to move forward to support 81st Infantry Brigade. Ninety minutes later the battalion (in fighting order) left their bivouac and joined the 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment outside Ypres, moving to the wood by Potijze Chateau. Heavy shell fire was recorded throughout the afternoon and evening. On three separate occasions the Battalion deployed beyond the British barbed wire to assault the German trenches North of Potijze Woods. Each time the attack was cancelled. However, the body of men in the open presented an easy target for German machine gunners; the War Diary records that ‘machine guns did considerable damage’. To compound the misery the rations failed to arrive.

That night the battalion occupied what was left of the GHQ Line, their left being 150 yards south east of Shell Trap Farm (later renamed Mouse Trap Farm), lying immediately north of the Wieltje – St Julien road. One company was held in reserve in trenches north of Potijze Wood. The War Diary describes 9 May as “One of the worst days shelling [the] Battalion experienced.” German machine gun and accurate sniper fire added to the difficulties. After a few days in these positions the Battalion was relieved, moving back to Vlamertinghe Chateau before returning to the trenches on 19 May. The War Diary records little of interest in the following few days other than intermittent shelling and sniping. The entry for 23 May records a “Quiet day and night”. The Dubliners were not know it but that quiet night was the calm before the storm.

Shell Trap Farm – 24 May 1915 gas attack (The Battle of Bellewaarde Ridge)

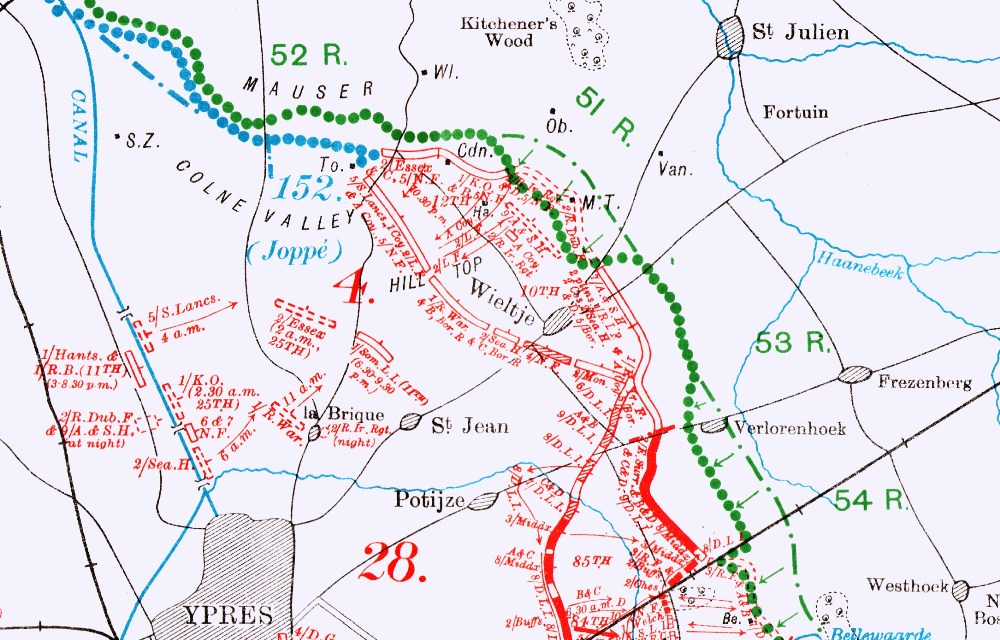

Official History map showing position occupied by 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers at Shell Trap Farm, 24 May 1915

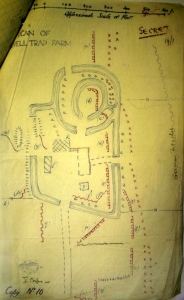

Detailed sketch map showing trench positions around Shell Trap Farm prior to 24 May gas attack. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diay (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

At 2.45am on 24 May the enemy attacked with gas. The area round Shell Trap Farm and to its immediate north west was most affected. A detailed report of the events of 24 May 1915 by Captain Thomas J Leahy (incorrectly transcribed as Linky in the report) is attached to the Battalion War Diary. Leahy describes that their C.O., Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Loveband has suspected gas may be used when inspecting the trenches at Shell Trap Farm earlier that night. He had personally warned all Company officers to be prepared whilst Major Russell (RAMC) had inspected all that Vermoral sprayers and warned each company about damping their respirators. Leahy’s report notes there were ten sprayers in working order that night, one with each machine gun and the remainder distributed along the trenches.

When seeing red lights thrown up from the German trenches (a signal for the gas release) Lt-Col Loveband shouted “Get your respirators boys, here comes the gas”. Leahy notes how little time they had; “we had only just time to get our respirators on before the gas was over us”. There was a gentle breeze, the gas cloud being very dense took about three quarters of an hour to pass over the Fusiliers’ position. German parties advanced in small numbers at 4.30am, occupying the British line north and to left of the Battalion’s trenches. With these trenches occupied, the Battalion was now subjected to enfilade fire. Under heavy shellfire and aided by part of two companies of the 9th Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders the Battalion held to their trenches to the end. The report makes harrowing reading, containing transcripts of signals sent by isolated parties within the farm complex. Even a hundred years after the event it is clear to sense the fear in 2nd Lieutenant Robert Kempston from B Company’s message which simply stated “For God’s sake send us some help. We are nearly done”. Kempston was killed later that day. Whilst speaking to officers outside his dugout Lt-Colonel Loveband was also killed when a bullet struck him through the heart.

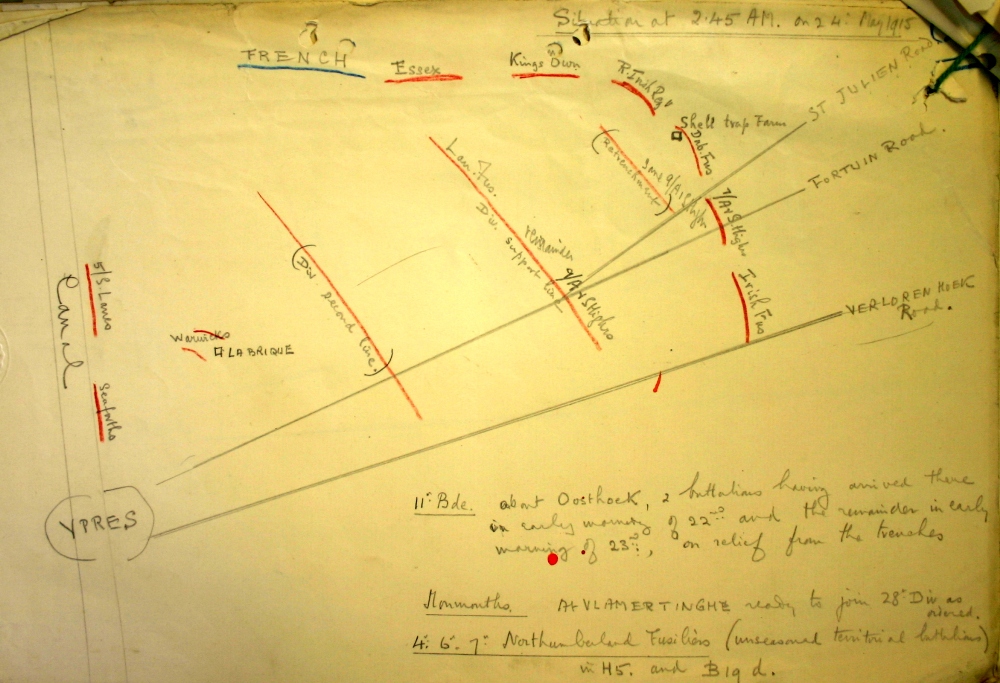

Sketch map showing situation at 2.45am on 24 May 1915. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diary (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

The War Diary records “Germans advancing under cover of enfilade fire, in small parties, finally occupied Battalion line by 2.30pm. Shelling ceased but rifle and M.G. fire remained accurate and constant, whenever a target presented itself, until dusk.” In the face of such a breakthrough it was decided, that evening, to withdraw to a more defensible line. Exhausted by their staunch defence the Battalion was withdrawn at 9.30pm and bivouacked on the west bank of the canal.

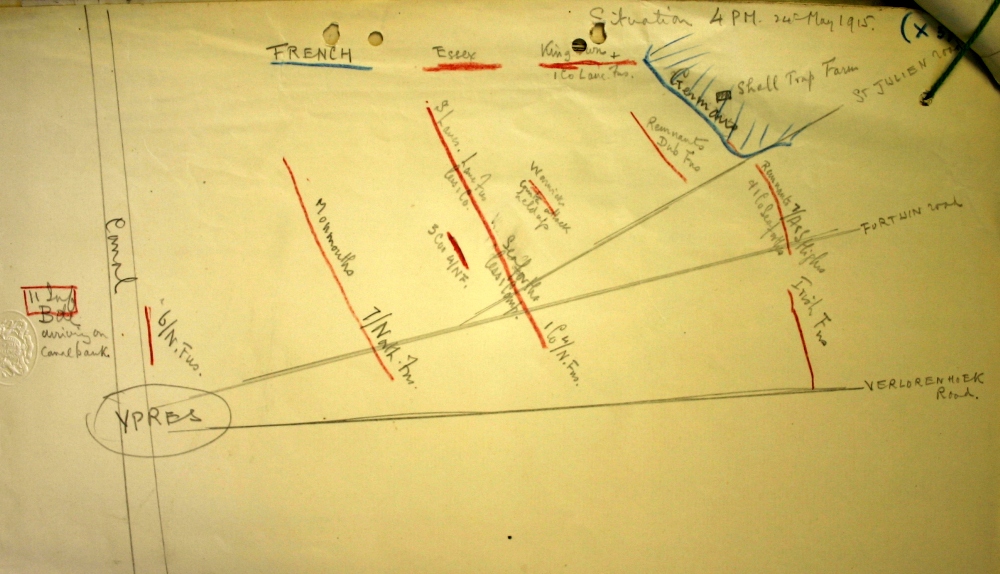

Sketch map showing situation at 4pm on 24 May 1915 after German gas attack. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diary (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

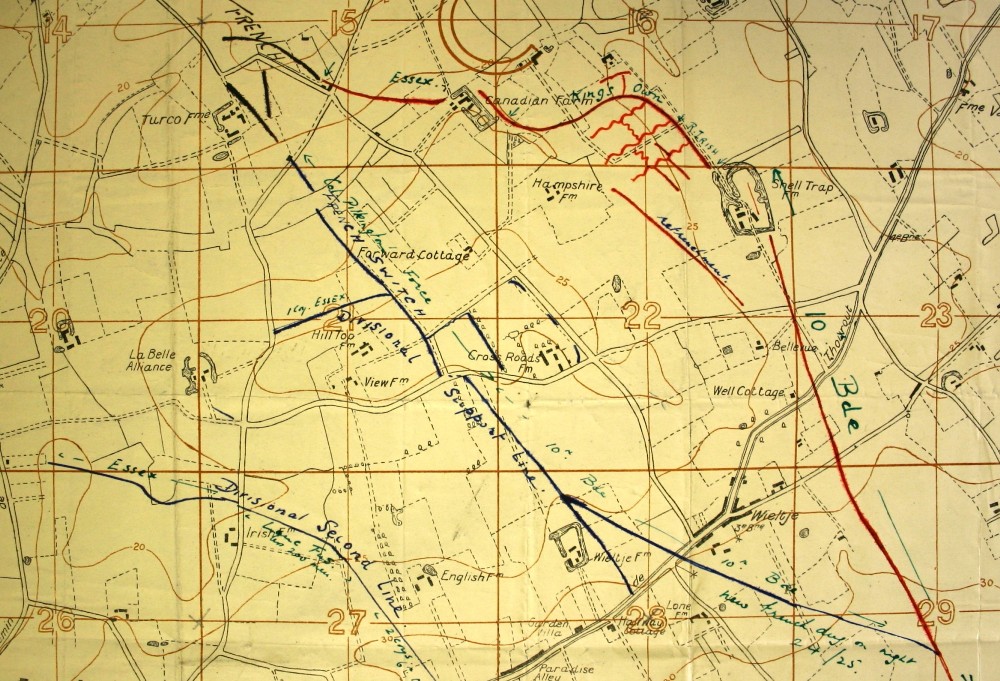

Trench map of positions around Shell Trap Farm. Red lines show the trench positions prior to the 24 May gas attack whilst the blue lines correspond to final positions after the attack. Image taken from 4th Division General Staff HQ May 1915 War Diary (NA Ref: WO95/1442) and is reproduced with permission from the National Archives.

The cost

The War Diary records the Battalion strength in trenches on the morning of 24 May was 17 officers & 651 other ranks. Such had been the ferocity of the fighting, the shellfire, rifle and machine gun fire with the addition of the night-time chlorine gas attack that, when relieved, only one officer and 20 other ranks crossed the canal. What remained of the Battalion (reinforced by a draft) moved back to Vlamertinghe Chateau the following day. The entire Battalion strength was only 2 officers and 190 other ranks.

Leahy’s report concludes with these words:

“When the wounded were sent away after dark there were no Dublins in front of Battalion Headquarters. From about 2.30pm there was no fighting in our trenches. Everyone held onto them to the last. There was no surrender, no retirement and no quarter given or accepted. They all died fighting at their posts.”

Inspecting the shattered remnants of the battalion on 28 May, General Sir William Pulteney commanding III Corps commented how sad it was to see so few remaining and emphasised the fact that the Battalion should console itself with the knowledge that those who had gone had “Done their job”.

Astonishingly, the Battalion (at full strength 1027 officers and men) suffered just under 1,500 casualties in one calendar month from 24 April – 24 May 1915. This figure clearly includes reinforcements who made up earlier losses. Most of these casualties were sustained during three distinct period in the line. I have copied the relevant dates from the summary given in full below:

- 25 April: 7 officers killed, 8 wounded. Other ranks: 45 killed, 80 wounded, 371 missing

- 9-10 May: 4 officers killed, 3 wounded. Other ranks: 37 killed, 60 wounded, 185 missing

- 24 May: 9 officers killed, 1 wounded, 1 gassed, 1 missing, 1 POW. Other ranks: 14 killed, 35 wounded, 547 missing

For more information Thomas Stephen Burke’s ‘The 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers and the Tragedy of Mouse Trap Farm: April and May 1915’ is well worth a read. Shell Trap Farm (renamed Mouse Trap Farm) stayed in German hands from May 1915 until its capture at the start of the Passchendaele offensive on 31 July 1917.

Working with ex-service personnel for ‘The Fresh Air Hut’ at Dunham Massey National Trust

In January I was invited to speak to a group of ex-service personnel who were working with the Military Veterans’ Service. Offering psychological therapy the Military Veterans’ Service provides help to veterans across the North West.

Dunham Massey National Trust’s successful Sanctuary from the Trenches; a Country House at War has recreated the Stamford Military Hospital in the state rooms in Dunham Massey. A doubling of visitor numbers has shown the general public’s interest in the subject. However, for 2015 the staff are keen to showcase further aspects of the medical treatment offered from 1917-19. Sister Bennett, the Hospital’s Matron was a keen advocate of outdoor healing practises. A pivoting wooden hut was situated in the garden at Dunham Massey, which provided sheltered outdoor space for soldiers. A picture in the archive shows wrapped-up patients out in the hut in the snow, receiving ‘fresh air’ and ‘sun bath’ treatments.

Dunham Massey’s ‘The Fresh Air Hut Project’ was designed to involve a team of volunteers working with the Military Veterans’ Service to create an interpretive visitor experience in an authentic replica of the pivoting timber hut. By using art therapy, the ex-service personnel could draw inspiration from their unique training opportunity and reflection upon their own personal experiences of military buy cheap tramadol online life.

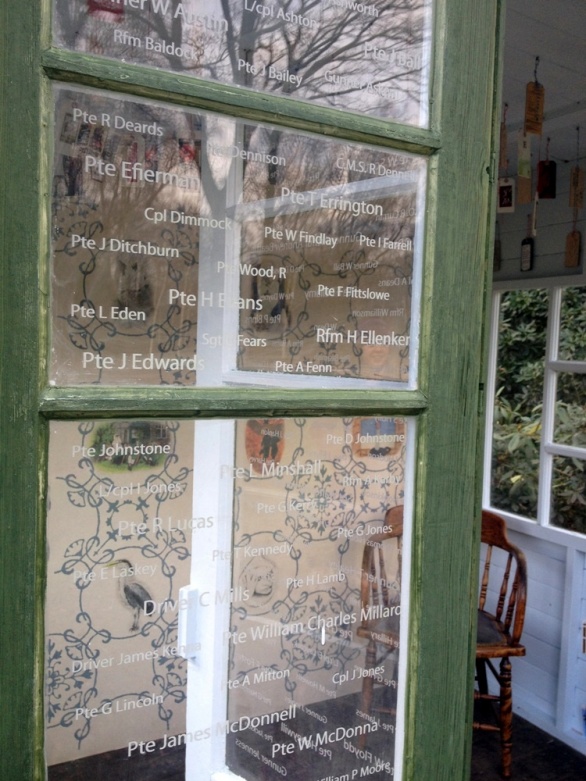

I spent a wonderful day with the veterans in early January, speaking about many of the stories of soldiers who had recuperated at Stamford Military Hospital. We were then treated to a tour of the house and able to watch recreations of soldier’s stories; the parts of soldiers and nurses being played by actors. With the information I provided the veterans were able to use parts of the stories in their art workshops. The result of their endeavours, the replica hut filled with artwork, was in situ when the house reopened in mid-February. I visited on the first day, 14 February, and was struck not only by the skill and variety of the artwork but the sense of calmness and solitude the hut offered. Tucked away from view, it felt as if one had stumbled across the hut. Windows etched with the names of soldier patients added to the overall feeling. My congratulations to the veterans who produced such brilliant work and thanks to the personnel who planned and worked with them on this.

Dunham Massey details via the National Trust website: http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/dunham-massey/