Posts Tagged ‘Messines’

Researching the war service of David Emanuel’s grandfather, John Leslie Emanuel, for BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’

In June I spent a day in Merthyr Tydfil filming with Yellow Duck Productions for their hit BBC Wales genealogy programme, ‘Coming Home’. Having worked with Yellow Duck on a previous series I was asked to research the wartime service of John Leslie Emanuel, grandfather to the fashion designer David Emanuel.

As was revealed in tonight’s broadcast, David never met grandfather who drowned in a tragic accident in December 1939. Whilst aware of his grandfather’s drowning, David had little knowledge of his wartime military service. We had a lucky start in that his grandfather’s service record survived. Using this and extant unit war diaries I was able to show David where his grandfather had served.

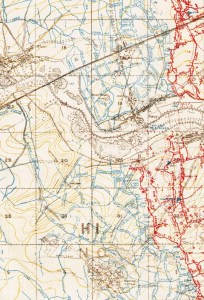

Trench map extract of the Roeux – Monchy area – positions occupied by 234 Machine Gun Company in summer 1917. Crump Trench runs just to the south of the railway line in the area west of the village of Roeux.

John Leslie Emanuel enlisted in February 1916 in the Sussex Yeomanry and proceeded to France in September of that year, joining the 10th Battalion Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment). He soon transferred to 124 Machine Gun Company, spending six months on the Western Front, mostly in positions facing the enemy on the Messines Ridge. His active service was interrupted by his evacuation back to Britain, suffering from P.U.O. (pyrexia of unknown origin).

Four months later, having recovered, been promoted to Corporal and now serving with 234 Machine Gun Company, he again proceeded overseas. The unit war diary recorded the men swam in the sea off Le Havre (noting the water was warm!) before moving to the Arras sector. The Battle of Arras had ground to a bloody halt in mid May 1917 but isolated actions continued into the summer. The main British effort for summer 1917 was focused on endeavours in Flanders. However, this did not mean that 234 MGC had an easy time of it in Artois.

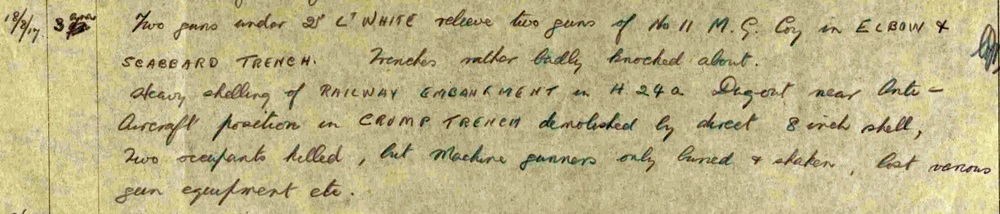

Extract from 234 Machine Gun Company War Diary 18 August 1917. Held at National Archives, Kew under Ref: WO95/1472/2 and reproduced with their permission.

The war diary is illustrative of the kind of routine and boredom of trench life but occasionally reveals periods of terror. 234 MGC was serving either side of the River Scarpe, providng support to the infantry occupying positions north of Monchy-le-Preux and in the village of Roeux, scene of bitter fighting in April and May. On 18 August an 8 inch German shell demolished a dug out near an anti-aircraft position in Crump Trench. Two of the occupants were killed outright but the machine gunners survived, despite being buried and badly shaken. A CWGC cemetery, named after Crump Trench now sits on the trench location.

A month later the company moved up to Flanders to take their part in the British offensive – the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). What struck me when looking at David’s grandfather’s story is that he was sent to a Corps rest camp for the entire period 234 MGC was in action near Langemarck. It is possible this period of rest was astonishingly good luck on his part. However, with the unit having undergone a fortnight’s training prior to their deployment north, it seems a strange time for a Corporal to be given leave. Detailed records are missing but it may have been that, after the rigours of the Arras sector, he simply needed a break. Despite popular modern misconceptions there was an appreciation of mental fatigue and it was understood that often men needed a rest away from the guns to recover. Put simply, no man whose mind was in a fragile state would have been of any use in the artillery war that dominated the Flanders battles. This omission may well have saved his life as the company inevitably took casualties when engaged in battle. Upon leaving Flanders 234 MGC returned to the Arras sector. In mid-December 1917 John Leslie Emanuel was sent back to Britain as a candidate for a commission. He never saw active service again, being discharged before the armistice.

David Emanuel gave an interview to Wales Online about his participation in ‘Coming Home’: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/whats-on/film-news/david-emanuel-war-hero-granddad-8149943

Earlier this autumn I spoke to the staff and volunteers at Dunham Massey Hall, a National Trust property in Cheshire. I had been approached some months before to help with their ambitious First World War project ‘Sanctuary from the Trenches’ which will see the hall will open its doors on 1 March 2014 as Stamford Military Hospital, the convalescent hospital in which 281 soldiers were treated between April 1917 and January 1919. Lady Stamford’s original plan to turn the hall over for use as a hospital for officers was altered, perhaps due to the sheer number of wounded men, and when the doors opened in April 1917 the hospital cared solely for ‘Other Ranks’.

My role in this project was to interpret the wealth of material gathered by the team of volunteers, pick a representative sample of men from those chosen and use their stories in a lecture to not only explain the conduct of the war in 1917-18 but also elaborate on the daily routine of trench warfare, evacuation of sick and wounded and medical treatment received by the men. The information uncovered by volunteers was prodigious; there was no shortage of material related to the soldiers’ stay at Stamford Military Hospital. What was lacking was an appreciation of where those men had come from, in what actions they had fought and been wounded and what happened to them after their recuperation.

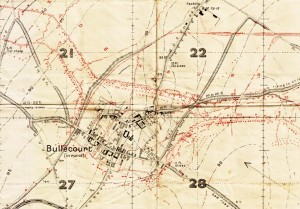

Bullecourt trench map extract. Two of the men who recuperated at Stamford Military Hospital were wounded here on 3 May 1917.

Casualties studied included a man of the 11th Rifle Brigade wounded near Havrincourt Wood in the push to the Hindenburg Line in early April 197, two men caught up in the Hindenburg Line itself at Bullecourt in May and a French Canadian wounded on Vimy Ridge. I was also able to use descriptions from my research into the Battle of Arras to illustrate the actions at Fampoux and Roeux in which a soldier of the 2nd Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment was badly injured. Moving northwards to Flanders I was able to look at the Battle of Messines (June 1917) with Private John Ditchburn, 9th Yorkshire Regiment, wounded close to Hill 60 on 7 June and two further casualties from the Third Battle of Ypres. Sources used included Medal Index Cards, Service Records (where available) and Census Returns. By scouring Brigade, Division and Corps files I was able to find appropriate maps to illustrate the exact area where the men had fought.

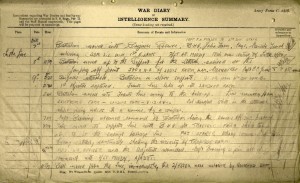

War Diary extract from 2nd Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment) for October 1917. One of the men who had been wounded at Arras, recuperated at Stamford Military Hospital, returned to the front and was killed in the Passchendaele offensive.

I was also keen to include soldiers wounded whilst not taking part in any major set-piece battle but in the daily business of merely ‘holding the line’. This offered a good opportunity to show the limitations of available documents. None of the men I researched were named in unit war diaries and so, in many cases, it was an educated guess as to the site of his wounding. Private William Johnstone, 1st Gordon Highlanders was hit by shrapnel in spring 1918 close to the city of Arras but from sources available I was unable to identity which day. His was a particularly sad story; after recuperating for over two months at Dunham Massey he was found to have shrapnel embedded deep in his head. Over time his condition deteriorated and he died of a cerebral abscess in hospital in Manchester. The final man I focussed on was even harder to research; Private Jenkins of the 1st Gloucestershire Regiment was wounded at some point during the autumn of 1918, the ‘Last Hundred Days’ of the war. His full identity remains unknown with neither christian name or regimental number noted in the records extant. I was keen to contrast this with some of the earlier soldiers I had researched where I had been able to provide highly detailed information.

Having prepared the research on these men I spoke at Dunham Massey Village Hall to two groups of volunteers on 18 September. I was heartened by the audience’s reaction, not only by the enthusiasm shown but also the interest in the men and the ‘Sanctuary from the Trenches’ project. I look forward to returning to Dunham Massey to see how the information has been used and what the ornate saloon will look like with furniture replaced with stark hospital beds. I would like to thank Charlotte Smithson and all those who work and volunteer at Dunham Massey for their help and enthusiasm with this project.

Our forthcoming project Sanctuary from the Trenches; a Country House at War tells the story of how Dunham Massey Hall became the Stamford Military Hospital, caring for 281 soldiers. Our collection gives us some information about the soldiers that stayed at Dunham, but we wanted to know more about their lives before they were treated here. Using our archive and other resources, Jeremy pieced together their stories. Jeremy’s respect for those that fought during the First World War made for a heart-warming lecture. He talked us through what our soldiers had experienced and left us feeling fondly affectionate for the brave souls who were cared for here. Over 100 volunteers attended the lecture and it was a big hit with them all – they haven’t stopped talking about it since. It provided the background of information for our volunteers needed in order to contextualise the Stamford Military Hospital’s role in the First World War. We’ll be asking Jeremy back, without a doubt!

Charlotte Smithson, Volunteer Development Manager at Dunham Massey

An interview with me discussing my research is available to view below:

For those interested my lecture is available in full here: http://vimeo.com/75168130

A dedicated page on the National Trust’s website with further details is available here: Sanctuary from the Trenches http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/article-1355804816003/

Further testimonials:

‘Jeremy Banning’s knowledge of the First World War is second to none and he is as good a presenter as you could wish for. A star attraction, I would suggest. So to have him come to talk to us Volunteers was a real treat. The presentation was so revealing and full of fascinating tales of soldiers directly connected to our Property’.

‘I am still buzzing and it is down to Jeremy Banning! Such a wonderful talk – please pass on my thanks.’

‘I want to thank you for enabling me to have and enjoy the privilege of attending Jeremy Banning’s presentation this morning. The whole experience was informative, exciting, thought provoking, uplifting and at the same time humbling. Jeremy’s enthusiasm and knowledge, for me and I am sure, all the other volunteers attending, made it a most memorable morning and I thank you, very sincerely, once again.’

‘A superb morning at Dunham Village Hall with Jeremy Banning – he really brought our soldiers to life, with such affection too. It was a privilege to attend’