Following in the footsteps of the 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade at the Battle of Arras (April – May 1917)

Earlier this month having spent a few days recceing sites and walks for upcoming trips I spent a day showing a client, Tony Wright, around the Arras battlefields following in the footsteps of his great uncle, S/30401 Rifleman Herbert William Victor Wright, 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade who was killed on 3 May 1917. It was most likely that Herbert had joined the battalion as one of nearly four hundred reinforcements received in January 1917. As such, the spring offensive at Arras would be his first major battle.

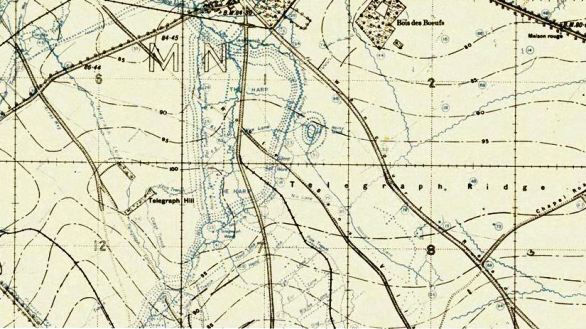

Sadly, Herbert Wright’s service record no longer existed and so we were unable to determine which company he had served in. However, with the knowledge that he would have been ‘in the area’ we started off by looking at the battalion’s role in the 9 April attack. The 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade was part of 42nd Infantry Brigade, 14th (Light) Division. The divisional objectives for 9 April were to capture the strong German position known as the Siegfried Stellung, (Hindenburg Line) which the Germans had fallen back to throughout the month of March. The hinge of the ‘old’ German line and new Hindenburg Line was the village of Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines. South of the village lay the 14th Division’s objective, the southern part of The Harp, a formidable position some 1000 yards long and 500 yards wide, full of tangled field defences. Along with Telegraph Hill to its immediate south its dominant position enabled German defenders to fire in enfilade northwards up Observation Ridge and southwards to Neuville Vitasse; its capture was absolutely critical.

Looking across the rising ground of The Harp. The 9th Rifle Brigade advanced across here on 9 April 1917

The role of the 9th Rifle Brigade on 9 April was limited to that of ‘moppers-up’. An initial assault was to be made against the southern portion of ‘The String’, a trench running down the length of The Harp, by the 5th Ox and Bucks Light Infantry and 9th King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Once captured the 5th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry would then pass through or ‘leapfrog’ the two battalions to capture the second objective close to the Blue Line running south from the rearward face of The Harp down the Hindenburg Line. Nearly seven hours after the initial advance and with these objectives taken B & D Companies of the 9th Rifle Brigade, under the command of Captain Buckley were to leave their positions in and around the old German front line to clear the ground between the Blue and Green lines within the Brigade boundaries.

They would also occupy an outpost line north east of the Tilloy – Wancourt road (now the D37). Considering the magnitude of the day’s fighting the Battalion war diary gives scant information about the work completed other than to record the final objective was gained by 1.30pm with one hundred prisoners and two machine guns captured. Casualties sustained were Captain D.E. Bradby killed , 2/Lt H.M. Smith wounded and fifteen Other Ranks wounded. Despite differing figures from those provided in Brigade records it is clear that losses amongst the 9th Rifle Brigade were extremely light when compared to other battalions within 42nd Brigade.

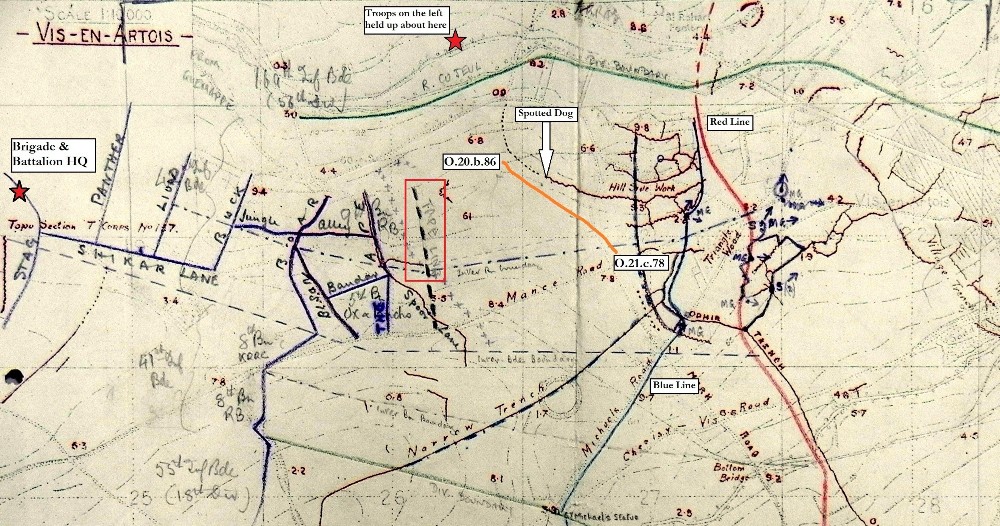

After relief on 12 April the Battalion spent time in training where they received a draft of fifty two reinforcements. On 23 April the Battalion began their march back to the battlefield, moving into newly captured positions between Guémappe and Chérisy on the evening of the 24th. The war diary records constant shellfire for this entire period; on one day alone 2/Lt J.M. Harper and a further sixteen Other Ranks were wounded. Between 30 April – 2 May the Battalion were in reserve but provided working parties to dig out a new communication trench named Jungle Alley running between the Ape and the Boar trenches before taking up their positions in the front line north of Chérisy on 2 May. The stage was set for a renewal of the offensive; three armies would be attacking along a fourteen mile frontage from Bullecourt in the south to Fresnoy in the north. Having suffered such comparatively small losses on 9 April the 9th Rifle Brigade was to take a leading part in the coming battle, attacking on the left of the Brigade next to the 5th Ox & Bucks Light Infantry. The 5th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry and 9th King’s Royal Rifle Corps were in Brigade Reserve.

The decision to launch the attack at 3.45am in darkness was contentious. Many commanders protested to no avail. A further complication for the 9th Rifle Brigade was their position nearer to the enemy than neighbouring units. As such, they were not to advance from their jumping off line until eighteen minutes after Zero Hour. The Battalion had two objectives; firstly to capture the Blue Line running in front of Triangle Wood and through Hill Side Work and then to push on to the Red Line, completing the capture of both positions. Advancing from a line 150-200 yards east of the front line marked by white tape fixed to the ground, the Battalion was to advance behind a ‘creeping barrage’ of artillery shells exploding in a slowly moving curtain across the battlefield.

Ten minutes before Zero Hour the first wave left the assembly trenches to line up on the tape. At 4.03pm they advanced, followed by the second wave that left the assembly trenches at Zero +42 minutes. In common with many units who attacked that dreadful day, no further report was ever received from the companies in the first wave. German artillery fire was extraordinarily heavy (lasting for over fifteen hours) with eight company runners either killed or wounded. Post -action reports noted the first wave veered to the right in the darkness, striking a new German trench wired and held by the enemy. Despite this, it was captured by Zero + 40 minutes and advance progressed. However, enfilade machine gun fire caused heavy casualties and ‘few, if any ever reached the rear of Hill Side Work’. All eight officers of the first wave became casualties very early in the day, some being wounded several times. Only seven NCOs of the first wave ever returned. The second wave fared no better. As their advance was in daylight they were subjected to machine gun fire sooner than the first wave and also came up against machine gun positions which had been established after or missed in the dark by the first wave, in addition to enfilade fire from across the Cojeul valley near St Rohart’s Factory.

Cross left in memory of Herbert Wright, 9th Rifle Brigade. Triangle Wood and Hill Side Work are on the horizon

The second wave was finally held up just in front of Spotted Dog Trench which was held by the enemy; they dug in along a line of shell holes about 600 to 700 yards in front of their original front line at Ape Trench. A German counter-attack against the 18th Division who had captured Chérisy forced their line back to its starting position; this action rippled northward with orders sent out to recall the Battalion. Such was the dominance of German artillery and machine gun fire (firing continuously from both flanks and from across the river valley) that these orders could only be communicated to two platoons; it being impossible to contact the remnants of the battalion occupying shell holes close to Spotted Dog Trench. On the evening of the 3rd two patrols were sent to recall one company holding a line of shell holes and strong point close to the German trench. Over the next couple of nights survivors of the 9th Rifle Brigade’s attack returned to the original British line. The Battalion’s casualties during the day’s operations were 12 officers and 257 Other Ranks. The 9th Rifle Brigade was relieved on 4 May before heading back to The Harp. This disastrous day marked the beginning of the end of the Battle of Arras. Desperate fighting continued for possession of Roeux, its infamous Chemical Works and Greenland Hill plus around Fresnoy which was recaptured on 8 May. However, by then British attentions were turning northwards to Flanders.

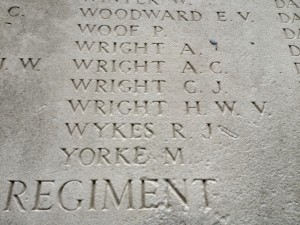

As Herbert Wright’s company is unknown it proved impossible to know whether he formed part of the first or second wave of attackers. Tony and I we walked the attack, passing the assembly trench positions, taped line from which the battalion advanced before moving to the final positions reached. It was here that Tony laid a small poppy cross in memory of his great uncle. Herbert Wright was one of ninety seven men of the Battalion killed on 3 May; all but two are commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the Missing. We visited the Arras Memorial and saw Herbert Wright’s name on Panel 9.

His remains may be buried in the grave of an unknown soldier or still be out on the battlefield. The Third Battle of the Scarpe, as the fighting over 3/4 May was named, was an unmitigated disaster for the British Army which suffered nearly 6,000 men killed for little material gain.

In the Official History, Military Operations France and Belgium 1917 Cyril Falls gives the following reasons for the failure on 3 May 1917 in the VII Corps frontage:

“The confusion caused by the darkness; the speed with which the German artillery opened fire; the manner in which it concentrated upon the British infantry, almost neglecting the artillery; the intensity of its fire, the heaviest that many an experienced soldier had ever witnessed, seemingly unchecked by British counter-battery fire and lasting almost without slackening for fifteen hours; the readiness with which the German infantry yielded to the first assault and the energy of its counter-attack; and, it must be added, the bewilderment of the British infantry on finding itself in the open and its inability to withstand any resolute counter-attack.”

This stark paragraph illustrates perfectly the battlefield during the 3 May 1917 fighting; nightmarish, terrifying and bloody. Having been at home for a week now I am still thinking about it and the windswept ridge between Guémappe and Vis-en-Artois.

“I spent an extraordinary day with Jeremy walking in the footsteps of my Great Uncle, who fell on May 3rd 1917 at the Battle of Arras. He did a wonderful job of balancing a very good explanation of the complexities of the overall battle itself with a highly emotional and personal end to the day of literally experiencing his final hours. As my Great Uncle was a private soldier, without detailed records of his service easily available, I was deeply impressed by how he brought together a range of different sources to nevertheless give me a really specific and personal understanding of what he and his comrades went through. It was an absolutely unforgettable experience”. Tony Wright

A good write up of the part played by one young officer, 2/Lt William Clarke Wheatley, former pupil at Sandbach School who was killed in the 3rd May attack can be found on Conor Reeves’ excellent website: http://sommejr.wordpress.com/william-clark-wheatley-3517/.

Another excellent and highly detailed account of a special trip. The personal nature of such visits are often more poignant than the more general purpose battlefield tours that we have both been involved with. Having been in the area just a few days before, I appreciate that in order to make the story really come alive, you need to have a good understanding of what was going on in the wider picture to then bring e personal element to life.

Well written Jeremy. Brought to life in superb detail. Really whets the appetite for future visits and as you indicate in previous blogs should spark the interest of the younger generations.

I’m always impressed by how vividly you bring these stories to life. Just reading your blog post I felt as if I’d walked alongside Herbert Wright.

Thanks Caroline – very nice of you to say so. Looking forward to October’s trip when I can do the same for you with Percy Honeybill.

Well written and presented blog.

I am puzzled though by your coverage of the time just after 12th April as i have been trying to understand how and where a George Edward Blinco was KIA on 19th April along with several others supposedly with the R B 9th Bn see list below

George Edward Blinco Buxton 19 Apr 1918 Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) Western European Theatre

Herbert Thomas Brazier Chelsham, Surrey 19 Apr 1918 Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) Western European Theatre

Edward Cave Marylebone 19 Apr 1918 Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) Western European Theatre

Albert Victor Codling Plaistow 19 Apr 1918 Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) Western European Theatre

Henry Walter Jordan Faversham, Kent 19 Apr 1918 Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) Western European Theatre

Lawrence Shaw Birmingham 19 Apr 1918 Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) Western European Theatre

Tom Whitham Ashton-under-lyne 19 Apr 1918 Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort’s Own) Western European Theatre

Some of these men died of wounds on 19th April but others are recorded KIA in the uk soldiers died in great war records. How sure are you that the 9th were on reserve during that period. What is your opinion on these records accuracy.

Value your thoughts

Roger m Blinko

You are looking at 1918 Roger. My blog related to April/May 1917.

All best,

JB

I found this while looking for information on the battle that took place on May 3, 1917. My great-great-uncle Charles Henry Gott was killed on that day (although listed as missing). He was a Trooper with Household Battalion. Can one assume his experience was similar to Hebert Wright?

Lisa – I have emailed you this information but for other interested parties….

The Official History (Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1917) compiled by Cyril Falls records the events of 3 May 1917 for the 10th Brigade, 4th Division (of which the Household Battalion were a part) thus:

“The 10th Brigade (Br.-General A. G. Pritchard) put three battalions in line: 1/Somerset L.I. (detached from the 11th Brigade), Household Battalion and 1/R. Irish Fusiliers. The Somerset, starting twenty minutes after the other two, was to capture Roeux in its own time. The 2/Seaforth Highlanders and 1/R. Warwickshire were to go through to the final objective, Delbar and Hausa Woods, a trench covering Plouvain, and Plouvain Station.

Once more the darkness caused hopeless confusion; even the Somersets, starting late, could see nothing as they passed through Roeux Wood. Part of the battalion reached the outskirts of the village, but was unable to hold its ground. On the front of the Household Battalion a German machine gun behind a wall held its fire till the line came level with it and then swept it in enfilade with devastating effect. A few men of this battalion and of the Irish Fusiliers reached the first objective, 500 yards east of the Roeux – Gavrelle road; a party of the first wave of the Seaforth was seen advancing towards the second objective; and troops of the Royal Warwickshire certainly reached the first; but in every case few returned to tell the tale.”

Hello Jeremy,

I have found your posts about the Battle of Arras and the events of early May 1917 very interesting. My great grandfather, Pte Thomas Johnson 28299 of 8th Battalion The East Surrey Regiment seems to have followed a similar path to that of Mr Wright’s relative, dieing on the same day it seems. Reading the East Surrey’s war diary next to your post made it possible for me to get some sense of the terror, confusion and bravery of that night. I am hoping to visit Cherisy in September. I wonder if you might know of any cemeteries nearby where the dead from that action might have been buried? My relative is recovered on the Memorial at Arras and has no known grave, but I would like to pay my respects at the grave of someone who may have fought with him. This link might be of interest: https://www.queensroyalsurreys.org.uk/war_diaries/local/8Bn_East_Surrey/8Bn_East_Surrey_1917/8Bn_East_Surrey_1917_05.shtml

Best wishes.