Posts Tagged ‘1918’

Following in the footsteps of Godfrey Hinnels with Hugh Dennis for ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’

Last January I spent three days filming with Hugh Dennis for Wall to Wall’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ series. We were following in the footsteps of Hugh’s maternal grandfather, Godfrey Parker Hinnels. Godfrey served with the 1/4th Battalion Suffolk Regiment from Spring 1917 until his transfer to the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment in March 1918. Despite having just over a year on active service Godfrey certainly saw his share of action, going ‘over the top’ at Arras and Ypres as well as fighting during the German Kaiserschlacht and the defence of Wytschaete in April 1918. This article is designed to provide more information on those units and their actions covered in tonight’s episode.

Last January I spent three days filming with Hugh Dennis for Wall to Wall’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ series. We were following in the footsteps of Hugh’s maternal grandfather, Godfrey Parker Hinnels. Godfrey served with the 1/4th Battalion Suffolk Regiment from Spring 1917 until his transfer to the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment in March 1918. Despite having just over a year on active service Godfrey certainly saw his share of action, going ‘over the top’ at Arras and Ypres as well as fighting during the German Kaiserschlacht and the defence of Wytschaete in April 1918. This article is designed to provide more information on those units and their actions covered in tonight’s episode.

Battle of Arras

Godfrey’s Suffolk battalion formed part of 98th Brigade, 33rd Division. It did not participate in the initial advance on the morning of 9 April 1917 but was moved up close to the front line on 12 April, occupying a position on the road between Henin-sur-Cojeul and Neuville Vitasse, the scene of bitter fighting on the battle’s opening day. The battalion war diary records ‘A great deal of burial and salvage work was done by the battalion in the vicinity of the trenches in front of the Hindenburg line’. Godfrey’s initiation into active service can hardly have been harsher; searching through the blanket of snow carpeting the battlefield for men killed a few days earlier. There followed a move into the Hindenburg Line itself for a spell in the trenches before the battalion’s major effort in the Arras offensive.

Hugh Dennis and I go through the Suffolks attack at the sunken lane in the Sensée valley. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

At 4.45am on 23 April 1917 a huge British artillery onslaught fell on to the German trenches signalling the start of the Second Battle of the Scarpe. Godfrey’s battalion was tasked with bombing their way down 2,300 yards of both front and support trenches of the Hindenburg Line to the Sensée River. Despite the support of tanks and artillery this was still a highly ambitious task, being prosecuted down a strong system of trenches, specially designed for defence. A deep tunnel ran under the support trench offering accommodation, headquarters and stores. The initial advance was spectacular with the Suffolks reaching a sunken road between Croisilles and Fontaine-les-Croisilles within two hours. Just 200 yards short of their objective they then came under sustained German fire. Later that day a strong German counter-attack pushed them back in both trenches – they ended the day close to the morning’s starting position. Despite taking a remarkable 650 German prisoners in the initial advance the battalion suffered over 300 casualties (about 50% of the battalion strength). This bloody day’s fighting is chronicled in great detail in ‘From the Somme to the Armistice’, the memoirs of Captain Stormont Gibbs MC, an officer in the 1/4th Suffolks.

The village of Fontaine-les-Croisilles bathed in evening sunshine. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

Passchendaele

Following their mauling in the Hindenburg Line the battalion’s losses were made up with reinforcements. Back to fighting strength they moved north to the coast before heading to Ypres to take part in the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). The battle had commenced on 31 July but unexpectedly heavy rainfall in August coupled with the destruction of the delicate Flemish drainage system by millions of artillery shells had reduced the landscape to a shattered Stygian moonscape of overlapping shell holes. Any advance had been limited but September’s improvement in the weather gave the battlefield time to dry out. Ironically, considering the common perceptions of Passchendaele, dust became a problem with roads and tracks watered regularly to restrict dust clouds caused by passing troops and transport.

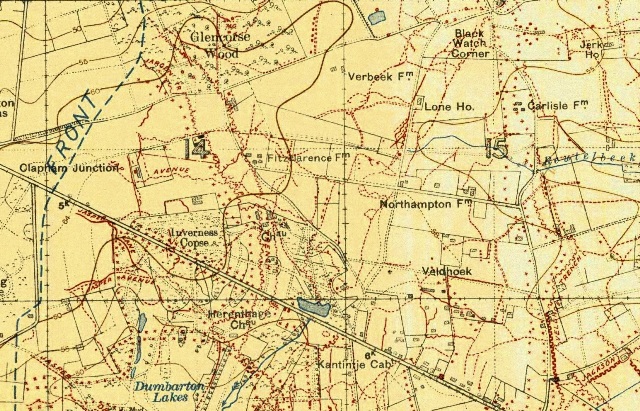

It was into this landscape that the Suffolks found themselves in September 1917. By 11.30pm on 25 September they were holding a line of trenches on the infamous Gheluvelt Plateau running between Fitzclarence Farm and Glencorse Wood, close to Polygon Wood. The plan was for the battalion to leave their positions, advance towards Black Watch Corner where a line of shell holes marked the British front line and join in the general attack at Zero Hour, 5.50am on the 26th.

The Suffolks were shelled prior to Zero Hour and heavy casualties sustained. The Battalion War Diary makes for depressing reading: ‘The heavy shelling, thick mist and darkness caused confusion and it was impossible for the men to keep touch but Platoon rushes were made and some Platoons made progress.’ Any great advance was impossible and by day’s end the battalion had only managed to advance to a line near Black Watch Corner. The battalion had achieved little and lost around 250 men in the process.

Extract from British trench map dated 14 September 1917 showing the Suffolks' battlefield - Fitzclarence Farm, Glencorse Wood and Black Watch Corner can be clearly seen.

The Passchendaele section was not broadcast but has been included as ‘unseen footage’ on the ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ magazine’s website here: http://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/footage/13822.

Winter 1917/1918 & Talbot House

The battalion took no further part in offensive action but spent the next six months in and out of the line on the Passchendaele ridge. When not in trenches the Suffolks were at rest in camps close to the small town of Poperinghe. Whilst not documented, it is highly likely Godfrey would have visited Talbot House – the “Every Man’s Club” situated in the bustling town’s heart. At our first meeting I had described Talbot House (also known as Toc H) to Mark Bates, the director of Hugh’s episode, and suggested a visit. It would be a good buy alprazolam .5 mg opportunity to show a typical soldier’s experiences when out of the line. We visited during our recce in December 2011 and, like so many before, I could tell Mark was taken with Talbot House. The house has a unique atmosphere rarely encountered in other buildings and I was delighted to see the Talbot House section so prominent in the final edit.

Spring 1918

On 1 March 1918 Godfrey headed south to the Somme where he joined the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, part of the 21st Division, holding trenches near the village of Épehy, once again opposite the Hindenburg Line. The exact reason behind his transfer is not documented but coincides with the 1/4th Suffolks becoming a pioneer battalion. It may have been that Godfrey’s skills were required more in a frontline infantry battalion as opposed to a pioneer battalion. He was soon into action as the Germans launched their Spring Offensive (Kaiserschlacht) on 21 March. Deluged with gas shells the Lincolns were attacked under cover of ‘a heavy white mist’. A day of desperate fighting followed with positions held around Chapel Hill before relief and retirement across the 1916 Somme battlefield. On 1 April the Lincolns entrained north to Flanders but hopes for a rest were short lived.

On 9 April a German attack south of Armentières heralded the start of the Battle of the Lys. A huge hole was punched in the Allied line and with his southern flank crumbling General Plumer, commanding the Second Army, ordered a withdrawal from the Passchendaele Ridge back to positions close to Ypres and the Yser Canal. The situation was desperate.

Wytschaete (now renamed Wijtschate) under a heavy sky. This view is looking north-east towards Staenyzer Cabaret crossroads. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

On the evening of 12 April with the battalion at less than half strength the 1st Lincolns were sent to defend the village of Wytschaete (nicknamed Whitesheet by British soldiers), holding a line between Staenyzer Cabaret crossroads and Bogaert Farm. Messines, directly to the south, had fallen two days previously and with Wytschaete the next village along the ridge an attack was almost inevitable. At 4.30 am on the morning of 16 April a heavy artillery bombardment pounded the British front line, the village and all approaches, lasting for 70 minutes. The official account of the operation details the subsequent events:

“Under cover of a dense fog the enemy attacked on the flanks of the battalion, and succeeded in breaking our line just North of the STANYZER CABARET Cross Roads, and at PECKHAM. Strong parties of the enemy then wheeled inwards and attacked both flanks of the battalion…Owing to the dense fog and bombardment it was impossible to get a clear idea of the situation and the Companies did not know they were attacked until the enemy appeared at close quarters. Fighting under every disadvantage, as the fog denied them the full use of Lewis Guns and rifles and made it impossible to locate the enemy, the battalion stood firm, and fought it out to the last. No officer, platoon post or individual surrendered and the fighting was prolonged until 6.30 am. Ample evidence of this is provided by the Commanding officer [Major Gush MC] and Battalion H.Q. who made a last stand at the Cross Roads, and did not leave there until 7 am. They, a mere handful of men, withdrew slowly, fighting all the way through WYTSCHAETE WOOD.” [National Archives Ref: WO95/2154]

The Lincolns had provided a magnificent display of defensive fighting in tremendously difficult conditions. During the action Godfrey was wounded in his index finger – a wound that prevented his return to frontline service. The following day a mere 5 officers and 82 other ranks were relieved to be joined by a further 21 stragglers who had become attached to other units during the fighting. Having gone into action with over 400 men, the Lincolns’ stubborn defence had been bought at a high price – the casualty rate was nearly 75%. The losses were not in vain as Brigadier General Cater commanding Godfrey’s Brigade noted how the ‘hard fighting left the enemy disorganised and unable to consolidate; and materially assisted the counter-attack delivered in the evening.’

At Wytschaete reading the account of the 1st Lincolns stand on 16 April 1918. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

Matching soldier’s reminiscences to actual actions can often be problematic but by studying Godfrey’s war service it soon became clear his story of fighting Germans on a hilltop must have related to the defence of Wytschaete. It was a remarkably satisfying conclusion to stand with Hugh Dennis on the same ground where his grandfather fought so gallantly ninety four years earlier.

My thanks to Paul Nathan for his agreement to use his photographs from filming, Mark Bates, Mike Robinson and all at Wall to Wall for their help plus Peter Barton for various maps & documents.

If you would like to read more about these battles and places then a very short suggested reading list is included below:

- Peter Barton with Jeremy Banning, Arras – The Spring 1917 Offensive in Panoramas including Vimy Ridge and Bullecourt (Constable, 2010)

- Jonathan Nicholls, Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917 (Leo Cooper, 2005)

- Peter Barton, Passchendaele – Unseen Panoramas of the Third Battle of Ypres (Constable, 2007)

- Paul Chapman, A Haven from Hell – Talbot House, Poperinghe (Cameos of the Western Front) (Pen & Sword, 2000)

- Chris Baker, The Battle for Flanders: German Defeat on the Lys 1918 (Pen & Sword, 2011)