Over the past few days Channel 4 have been showing trails for Thursday’s Time Team Special entitled ‘The Somme’s Secret Weapon’ and I have seen hits on the various articles on my website rocketing. I am heartened by the interest, and having seen the longer two-hour version of the film at a special event on Monday night at the Royal School of Military Engineering at Chatham I am confident that the visual impact of the film will attract plenty more interest. It is surely one of the most intriguing – indeed almost unbelievable – stories of the war. I have noted that many people are searching for the location of the dig site and I thought it appropriate that interested parties should be aware of the birth, the evolution and the structure of the project.

Initial stages

The idea of searching for the flamethrower was first mooted in 2005 when Peter Barton and I were working on our Somme panorama book. The book, now revised and back in the shops, covers the battle in its entirety but includes a lengthy section on the extraordinary story of the use, mis-use and lack of use of a considerable network on shallow tunnels dug under No Man’s Land by Royal Engineer Tunnellers in preparation for the opening of the battle. They were known as Russian Saps.

The Somme - the unseen panoramas by Peter Barton with Jeremy Banning. Published by Constable & Robinson.

In certain sectors on 1 July 1916 they were not used to their full potential whilst in the southern part of the British line the tunnels, terminating close to the German front line and integral dugouts, contained a variety of schemes to neutralise the enemy. These included substantial mines to destroy strongpoints, smaller bored charges to blow in dugouts, manholes close to the German trenches for the swift deployment of attacking forces into the line, trench mortar positions and machine gun emplacements emanating from tunnels in the middle of No Man’s Land, and perhaps most amazingly, huge flamethrowers for firing 100-metre jets of burning oil across and along German positions. The idea was to create a complex mixture of surprise and terror that would materially assist the British infantry to cross No Man’s Land and capture the enemy front line in a less molested manner than normal. It was the flame-throwers, however – the Livens Large Gallery Flame Projector – that seized the imagination, especially as they have received such scant attention in the mountain of literature associated with the Somme.

The projectors were almost 20 metres long, weighed 2.5 tonnes, and required a 7-man crew. Their placement in a tunnel beneath No Man’s Land was to attain an effective firing pattern some 50 or 60 metres from the German lines, and of course to keep their existence secret until the very moment of firing.

The Livens Large Gallery Flame Projector being tested at Wembley. Copyright National Archives. Reproduced with permission from NA file MUN5/385.

We knew that four had been planned for use on Z-Day. Two were deployed successfully from tunnels just to the west of the Carnoy-Montauban road whilst another was damaged and unused. The machine that really caught our attention was the one that was to have been fired from Sap 14 at a position in the British line between Bois Francais and Mansel Copse on the 7th Division frontage.

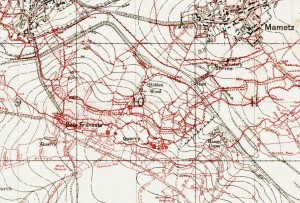

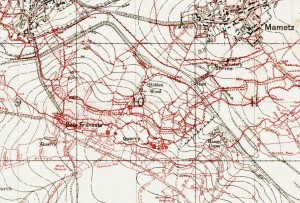

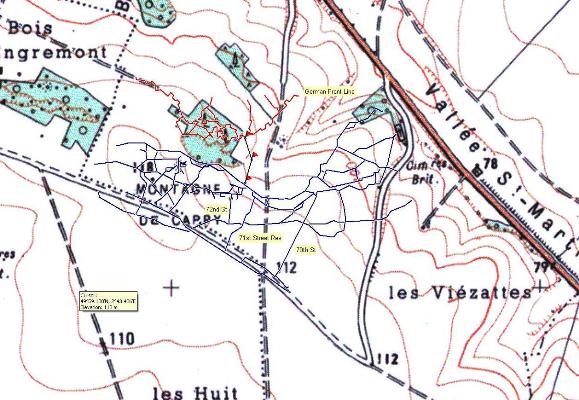

Trench map of the Fricourt - Mametz area dated June 1916. The tiny blue dot marks the site of the start of Sap 14 which was to house the flamethrower.

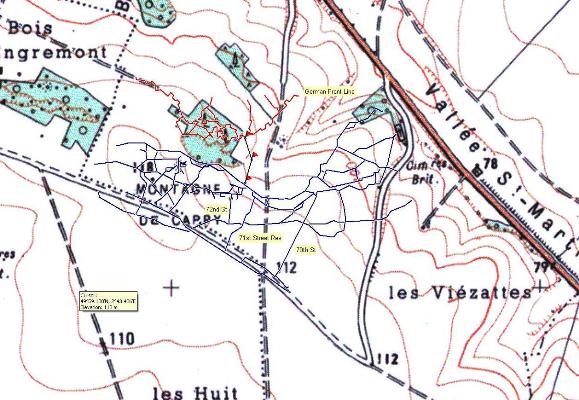

British (blue) and German (red) trench lines overlaid on a modern IGN map. The route of Sap 14 is marked by the red triangles. Courtesy of Iain McHenry using Linesman

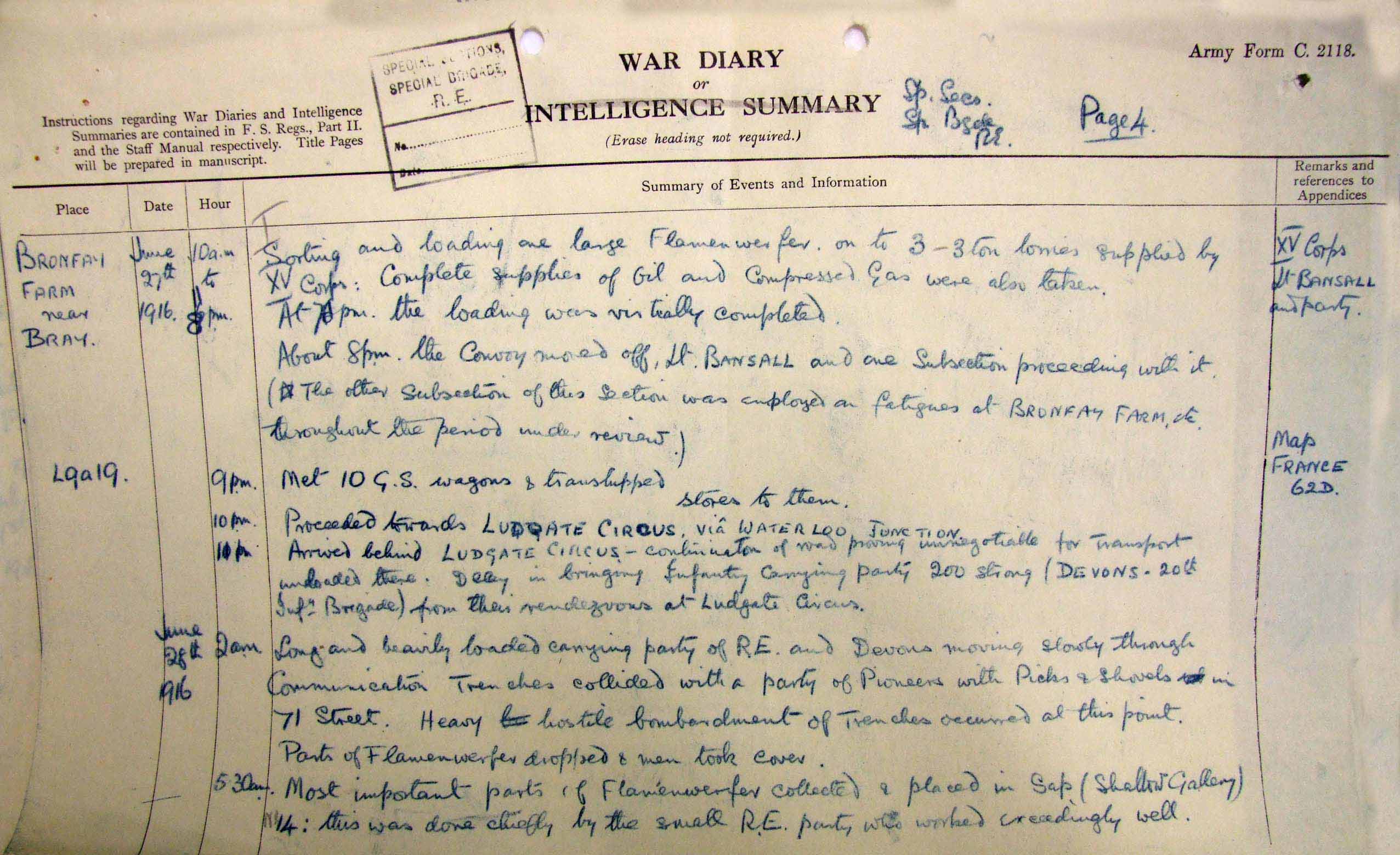

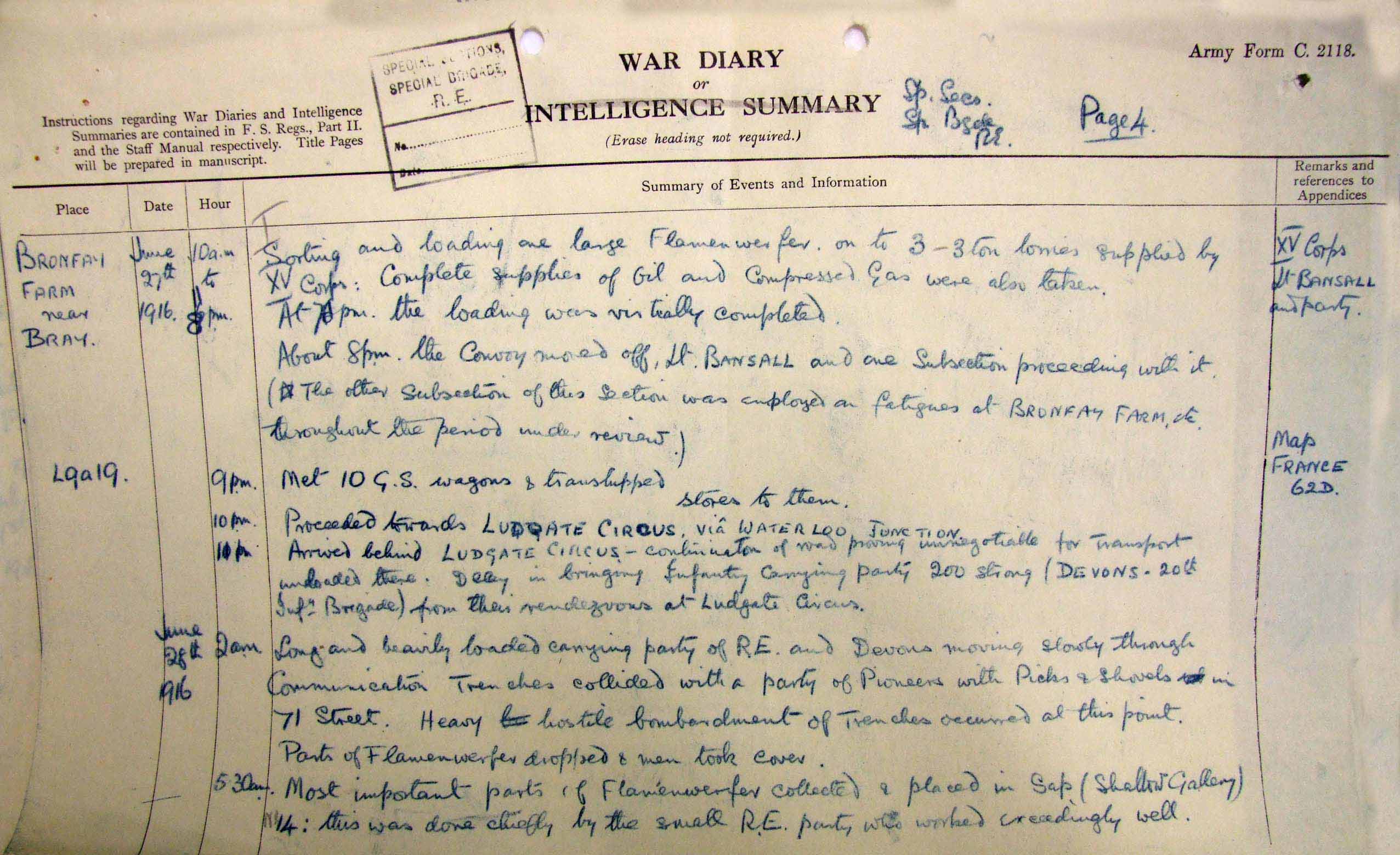

The Special Brigade war diary showed that on 28 June the machine had been brought up to the front line along a communication trench called 71st Street by a party of around 250 R.E. and Devons (8th or 9th Battalion) but that heavy shelling of the area meant the parts had to be dropped whilst the men took cover. The most important parts were then picked up by the R.E. and placed in the entrance to Sap 14 for safety. However, this inclined entrance tunnel was then hit by a heavy shell which sealed up the end of the sap for 20 feet, ‘burying vital parts of the flammenwerfer beyond recall’. [Special Sections RE War Diary – ref: WO95/122]

Extract from War Diary of Special Section RE for June 1916. Copyright National Archives. Reproduced with permission from NA file WO95/122.

Preparation

It was this tenuous but enticing line in the war diary that was the catalyst for the project. Peter Barton’s knowledge of how the R.E. worked and the sequence of events subsequent to 1st July, combined with our archival research persuaded him that some of those parts would not have been recovered. His relationship with Canadian television producers Cream Productions was already established as a result of previous documentary work and Cream agreed to take on this ambitious and indeed risky project. Peter then spent weeks travelling between the UK and the Somme for myriad meetings for permissions and logistics – far too much to catalogue here but his workload was prodigious and the entire cheap tramadol online overnight project would not have been possible without this necessary but unglamorous work. On one of our first recces to the projector site we had a chance encounter with farmer Eric Delporte on whose land the old trenches and sap run through. After some initial scepticism he soon willingly gave use of his field free of charge, refusing any payment for ground rental or for lost crop yield on the basis that he owed it to the young British soldiers lying in the several nearby cemeteries. M. Delporte been the perfect host thereafter – a true gentleman and friend to us all.

Using trench maps and Linesman on one of our recces to the site. The village of Mametz lies in the low ground at top of image

To cut a very long story short, by spring 2010 the dates for the dig had been fixed – it would be the final three weeks of May. The project brief was to study Sap 14 and the nearby trenches, enter and survey the saps if possible, and to locate and recover parts of the 1916 Flame Projector if still in situ.

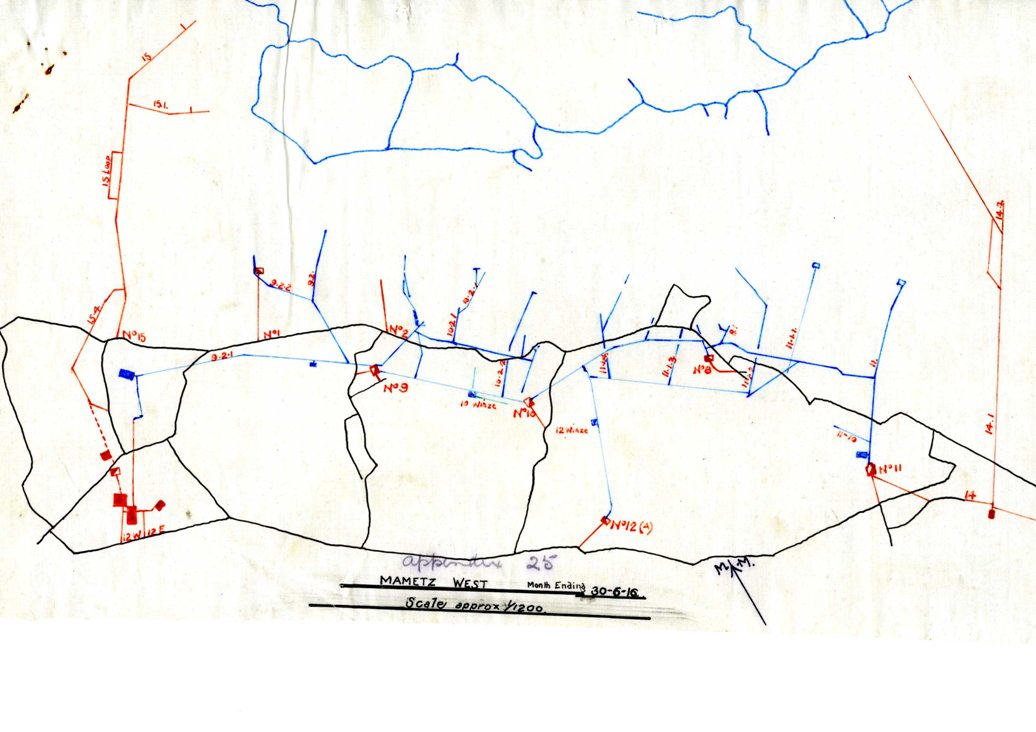

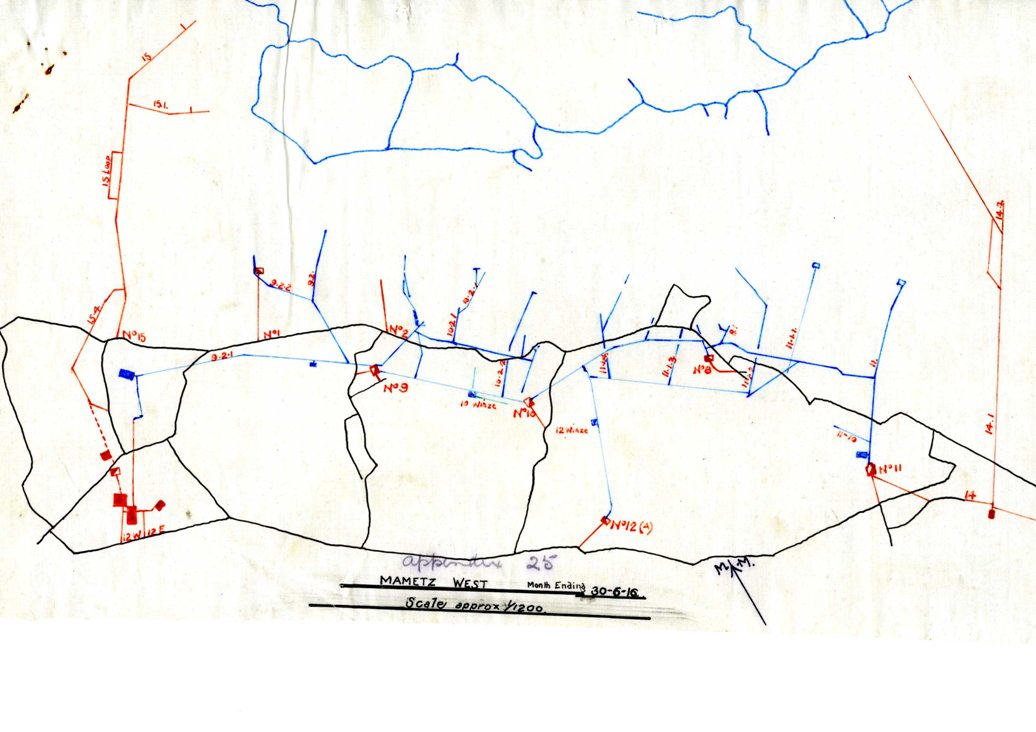

Map from war diary of 183 Tunnelling Company showing Mametz West secton. The flamethrower was to fire from the spur of Sap 14 on right of image. Image copyright National Archives. Reproduced with permission from NA file WO95/406.

The excavation was officially authorised by the French authorities and was under the archaeological control of Dr Tony Pollard and Dr Iain Banks of the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, Glasgow University. We received enormous and invaluable assistance from the Historial de la Grande Guerre, the Préfecture de la Région Picardie, the Conseil Générale de la Somme, M. Stéphane Brunel and the Mairie of Mametz, Mines Rescue, Bactec International and the Corps of Royal Engineers. Most touching was the response of local businesses. As a result of visits by Peter with Francois Bergez (at present the acting Director of the Historial) they sponsored fencing, portakabins, water bowsers, digging machines, portable toilets, etc – all free of charge.

Archival research

I had carried out extensive archival work in the year before the dig, not only investigating as many files as possible with regard to the production, testing and deployment of the Livens Large Gallery Flame Projectors for the start of the Somme offensive but also the use of Russian Saps along the entire British battle front. Our colleague Simon Jones added further invaluable information to the database. I also looked into the subsequent use of the flame projector in September 1916 at High Wood and in front of Guillemont. The object of this intensive work was to gain a detailed understanding of the use of the machine but also to try and unravel how and why decisions were made on the use of the saps. I compiled a 65-page report including any mention of the potential use of flame projectors and saps from war diaries ranging from Army level down through Corps, Division, Brigade and Battalion and, of course the Tunnelling and Field Companies of the RE. Between Peter and I we spent months getting as well-versed in all matters subterranean as possible. Only by having this level of preparation did we feel prepared to start.

The dig – May 2010

The dig ran throughout May and was attended by hundreds of people – locals and battlefield visitors alike. The team adopted an ‘open house’ policy, and many people came to the site every day to watch our progress. On the second Saturday of the dig we had an official open day which was attended by several hundred people. Detailed presentations were given in French and English and we displayed many of the artefacts we had recovered. The results of the dig were spectacular and after three weeks solid work it was a tremendous feeling of privilege for us all to have worked on such a project and to have developed such close and ongoing links with many of the local people.

Finding out more

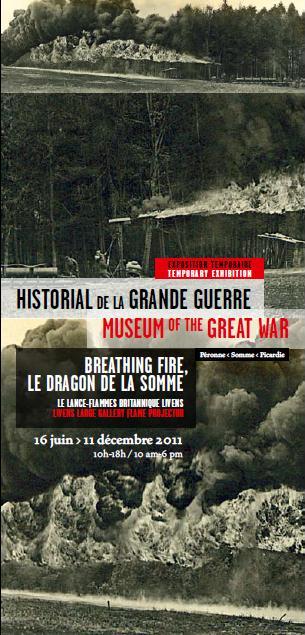

This post has been deliberately sparse with information on the dig itself for two reasons. Firstly, the international version of the film will not be aired until the autumn and therefore would not want to pre-empt this programme. Secondly, a huge amount of material will be on display in the forthcoming exhibition entitled ‘Breathing Fire – Le Dragon de la Somme’ to be held at the Historial at Peronne. This exhibition, curated by Peter, will incorporate a great deal of extra information, display the salvaged flamethrower parts, and (most surprising of all, perhaps) include a full-scale replica of the Livens machine. This is at present in the process of being built by metalwork students in Amiens. The exhibition will run from 16 June – 11 December 2011. An academic report on the Mametz dig by Tony Pollard and Iain Banks will be available in the next edition of the Journal of Conflict Archaeology.

How the Royal Engineers were persuaded to build and fire a working full-size modern version the flame projector is another story….but we thank and salute them.

By Jeremy Banning

A downloadable version of this flyer in pdf is available by clicking on the link below. Please feel free to disemminate this information to all your friends and battlefield visitors. It promises to be a terrific exhibition and for many will be the first chance to see parts of the Livens Flame Projector, buried in the Somme mud for 94 years.

A downloadable version of this flyer in pdf is available by clicking on the link below. Please feel free to disemminate this information to all your friends and battlefield visitors. It promises to be a terrific exhibition and for many will be the first chance to see parts of the Livens Flame Projector, buried in the Somme mud for 94 years.