Posts Tagged ‘Newfoundland Regiment’

Writers battlefield trip to the Somme & Arras – October 2012

Earlier this month I finished an extraordinary week’s work at La Boisselle followed by four days guiding a group of writers around the Somme and Arras battlefields. Last year I had taken Vanessa Gebbie on a bespoke tour following in the footsteps of the 14th Battalion Welsh Regiment (Swansea Pals). She had been extolling the virtues of the battlefields ever since and had cajoled other writers to join her for a few days away.

Somme

After picking up my passengers and hire car in Lille we headed south to the Somme. Our first port of call was to the Glory Hole at La Boisselle where I was able to take my group underground. BBC News were covering our work on site that day and it was exciting to stand at the top of W Shaft and hear the filming taking place below for that night’s Six O’Clock News. Vanessa has written about this on her blog here. After a visit to the Lochnagar Crater we stopped at Becourt Military Cemetery and Norfolk Cemetery en route to our comfortable accommodation at Chavasse Farm, Hardecourt-aux-Bois.

“I can’t tell you what an amazing time I had on our trip. You are a natural – to call you either a historian or a tour guide is to miss the point entirely, I think. You brought it alive for us, you animated the land, the people, the history, in a way I don’t think I’ve ever experienced. There wasn’t one minute when you were talking where I was bored, where I zoned out. You made me want to know everything. And more than that, you inspired me to think about identity, nationality, what I might be prepared to die for.” Tania Hershman

The next day was spent on the Somme starting in the southern sector at the junction of British & French forces between Maricourt & Montauban. Stops that morning included Suzanne Communal Cemetery Extension to visit the graves of 18th Manchester Regiment men killed in May 1916 when German mortar fire blocked their mine shaft at Maricourt, the Carnoy crater field where I explained about the use of the Livens Large Gallery Flame Projector on 1 July 1916, Devonshire Cemetery at Mametz and then down to the impressive Red Dragon of the 38th (Welsh) Division Memorial at Mametz Wood. Despite heavy rain most of us had a walk up the slope from Death Valley to look at positions occupied by the 11th South Wales Borders and 16th Welsh in their unsuccessful 7 July attack on the Hammerhead. After a coffee and change of clothes we headed back out. Stops included Guillemont Road Cemetery, High Wood and the Nine Brave Men (82 Field Company RE) memorial in Bazentin-le-Petit before lunch at Old Blighty Tea Rooms, La Boisselle.

The remains of the afternoon was spent at Aveluy Communal Cemetery Extension, Mash Valley and the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme before stopping at Flatiron Copse Cemetery, Mametz on our way back.

Over dinner that night I learnt one of my party had a relative with the 3rd Coldstream Guards who had been killed in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette on 15 September 1916. Our first stop the next morning was on the road between Ginchy and Lesboeufs to look at the starting positions for the attack. Guardsman Ernest Saye is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial so there was a chance his remains were still lying in the fields before us.

We paid our respects at the Guards Division Memorial, Lesboeufs before a stop specifically requested by Vanessa at Morval British Cemetery. This quiet spot contains 38th (Welsh) Division casualties killed in the capture of Morval on 31 August/1 September 1918. After stops at the Cedric Dickens Cross and Delville Wood Cemetery & Memorial we headed north of the Roman Road to Thiepval to pick up where we had left off the previous day. Stops included the Ulster Tower Newfoundland Memorial Park, the Sunken Lane at Beaumont Hamel and then over the Redan Ridge for a picnic lunch in the majesty of at Serre Road Cemetery No.2 where the Somme part of our tour ended.

Arras

En route north we stopped at Ayette Indian & Chinese Cemetery before arriving at Neuville-Vitasse Road Cemetery, Neuville-Vitasse where I set the scene for the Arras offensive. The elevated position offers a fine viewpoint from which to show the southern sector of the battlefield with Monchy-le-Preux, Henin Hill and the route of the Hindenburg Line clear to see.

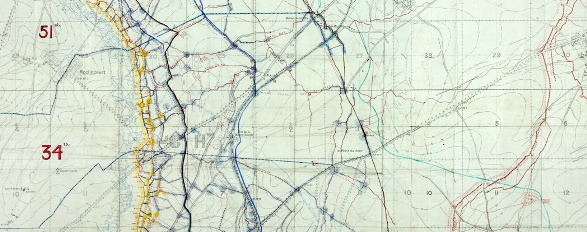

Poring over maps of the Arras battlefield at Neuville-Vitasse Road Cemetery. Thanks to Vanessa Gebbie for her permission to use this image.

After a visit to Cojeul British Cemetery to pay our respects at the grave of two Victoria Cross winners, Private Horace Waller and Captain Arthur Henderson we headed up to the open windswept ground of Henin Hill where we had a good look around a surviving German ‘mebu’ concrete pillbox, part of the Hindenburg Line defences in the area. After repeatedly getting in and out of the car we were keen to stretch the legs and so took a walk to Heninel-Croisilles Road Cemetery where I read the poet Siegfried Sassoon’s account of being wounded nearby. We then walked down to Rookery Cemetery and Cuckoo Passage Cemetery.

Our next stop was on Wancourt Ridge outside Wancourt British Cemetery where I read John Glubb’s detailed account of the bridging work undertaken by 7 Field Company RE across the River Cojeul in the valley before us on 23-25 April 1917. The landscape is wonderfully easy to match up to Glubb’s descriptions and offers the chance to imagine the scene 95 years ago. Afterwards some of us walked up to the site of Wancourt Tower. Our final stop of the day was the rarely visited but rather beautiful Vis-en-Artois Memorial. One of our party Caroline had a relative commemorated on the panels. Percy Honeybill, 1st King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment) was killed on 2 September 1918 attacking the Drocourt- Quéant defences.

Our final day saw us head to Arras for a croissant and coffee breakfast in the Petite Place before a visit to the Arras Memorial to the Missing and Faubourg-d’Amiens Cemetery. We then headed out along the Arras-Cambrai road to find the spot between Guémappe and Cherisy where Third Army Panorama No. 556 was taken on 6 May 1917. Standing close to the spot where the image was taken it offers an ideal opportunity to visualise battlefield conditions in May 1917. Our next stop was at Kestrel Copse to see the new cross for Captain David Hirsch VC. We then headed north to Monchy-le-Preux where I explained the magnificent action which resulted in the capture of the village on 11 April 1917. One of our party’s grandfather had served in the Essex Yeomanry. I was able to show her Orange Hill and the fields which her grandfather would have galloped across on 11 April 1917. We then headed up Infantry Hill where I told of the disastrous Newfoundland and Essex Regiment attack on 14 April and the subsequent action by the “Men who saved Monchy”.

Crossing the River Scarpe to Roeux, we visited the site of dreaded Chemical Works, now a benign Carrefour supermarket and garage. I always find it a pity that there is nothing on the site to show the ferocity of the fighting here in April and May 1917. Lunch was taken in Sunken Lane Cemetery at Fampoux (written about here by Vanessa Gebbie ). We discussed the terrible fighting for Roeux and the 11 April attack by the 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers. After visiting Gavrelle we headed north to Vimy Ridge, visiting the trenches and Walter Allward’s masterpiece, the Vimy Memorial where we bumped into my brother Mark guiding a group. What a small place the battlefields are sometimes! There followed an interesting journey back to Lille Europe station where the car was returned in a rather muddier state than it had been when picked up.

My thanks to Vanessa, Tania, Zoe, Angela and Caroline for being such good company and making the trip such a delight. I am already planning the itinerary for 2013!

“Thank you is really an inadequate word to convey my feelings about the weekend. I still feel as if I’ve been to a different place and had my life changed. I’m not quite sure how you managed it but it felt as if you really took us back in time to 1914, 1916, 1917 and 1918 and that we were standing alongside the men waiting for the whistles to send them over the top and later dragging or rolling themselves back to the safety of their trenches. I thought I knew a bit about the First World War having done a history degree and having read the poetry. At an intellectual level I suppose I did know about the war but emotionally I had no idea what it was like for the men and that experience was what you gave us with the maps, the panoramas and all the stories. Over the last few days they lived and breathed again. It’s difficult to pick out my favourite moments as everything felt like a highlight. I can’t remember if it was Tania or Zoe who said they’d never before come across a guide who didn’t bore them for a second. Actually ‘guide’ isn’t the right word – the ‘expert’ comes closer but also the ‘enthusiast’ brimming over with things you wanted to share.” Caroline Davies

Having just returned from three days in Arras where I gave a lecture at the Carrière Wellington about the Battle of Arras (April-May 1917) I am heartened by the increase in interest shown in the spring offensive. There is even a plan to tweet updates from the battle which should appeal to those using social media. I thought it a good opportunity to write a short article on the first stage of the battle – the First Battle of the Scarpe which ran from 9 – 14 April 1917. If time and work permits I will do the same for the Second (23/24 April) and Third (3 May) Battles of the Scarpe.

The view from the British trenches at Roclincourt. Highland Cemetery now sits on the position of the German front line. The line was assaulted on the morning of 9 April 1917 by units from the 51st (Highland) Division.

Introduction

Easter Monday, 9 April 1917 was a momentous day which saw the start of the Battle of Arras. It is best known in Canada for the attack and capture by all four Canadian Divisions (operating together as the Canadian Corps) of the previously unconquered heights of Vimy Ridge. It must be remembered that this action, whilst quite rightly lauded was undertaken to protect the northern flank of the main Arras battle front. Sadly, and almost inexplicably the main effort by troops of General Sir Edmund Allenby’s Third Army have been largely neglected by historians, television documentary producers and British battlefield visitors who all head north to Flanders and the blood-soaked fields around Ypres or south to the Somme. I cannot understand this omission as to me, Arras is the most interesting battle of the war offering a major element in the evolution of warfare. By the end of the offensive I would argue that, to many, the prospect of a final victory almost disappears from the Allies’ view.

The British attacks at Arras were part of a larger Anglo-French offensive planned for spring 1917. The author of this scheme was General Robert Nivelle, commander-in-chief of the French armies on the Western Front, who proposed three separate attacks. Two of these astride the Rivers Aisne and Oise would be French led. Great Britain, as the junior partner in the alliance was to launch a major diversionary attack in the north around Arras. It was not what Sir Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of the British forces wanted, but faced with such a huge French effort there was no other choice but to accept. The German retreat to the pre-prepared positions of the Hindenburg Line (Siegfried Stellung) rendered the attack on the Oise redundant. However, the major offensive on the Aisne and the British diversion at Arras would still go ahead as planned.

9 April 1917 – the opening day

Easter Monday, 9 April 1917 was, in the main, a great success for the attacking British and Canadian forces. Despite the unseasonal sleet, snow and severe cold the Canadian Corps captured the vast majority of Vimy Ridge and British advances to the south were also impressive. An advance of over three and a half miles was achieved by the 9th (Scottish) Division and the ‘leapfrogging’ 4th Division who captured the village of Fampoux. This advance was the longest made in a single day by any belligerent from static trenches.

An extract from XVII Corps battle plan showing objectives for the 34th Division including the Point du Jour. Ref: WO153/225. Copyright National Archives & reproduced with their permission.

South of the river attacking British divisions also fared well with Observation Ridge and Battery Valley captured. However, the planned capture of the village of Monchy-le-Preux on its hilltop plateau and Guémappe were not realised. Moving south of the Arras-Cambrai road the successful capture of The Harp and Telegraph Hill can also be viewed as particular triumphs. However, south of the Roman road the British were now attacking the newly constructed Siegfried Stellung (known to the British as the Hindenburg Line). The intelligent siting and design of the Hindenburg Line, coupled with the inability of British artillery to destroy barbed wire sufficiently made the attacks in the south a costlier and much more difficult task. Neuville Vitasse was captured but the two divisions to the south of the village suffered grievously in their attacks.

The night of 9 April saw Germany’s fate in the balance. If British success could be exploited then it was very possible a potentially disastrous breach in their line could lead to a full-scale German retreat. Sadly, for the British, the success of 9 April was the zenith of their action at Arras. Disorganization, breakdown of communications, dreadful weather and the perennial problem of moving the artillery forward over heavily bombarded ground resulted in little concentrated action taking place on 10 April. This delay was exactly what the Germans needed – time to reorganize and strengthen their defences.

First Battle of Bullecourt

The next day, 11 April was a pivotal day of fighting. General Sir Hubert Gough’s Fifth Army attacked in the south at Bullecourt. The hastily constructed plan has been to use tanks of the Heavy Branch Machine Gun Corps to crush the thick belts of barbed wire protecting the Hindenburg Line. When these failed to arrive on time Australian troops broke through the wire, fighting their way into the Hindenburg Line. By midday they were faced with the Germans closing in on them on three sides and were forced to retreat across No Man’s Land to their own line. Over 2,000 men were taken prisoner – the largest number of Australians captured in the war.

The Capture of Monchy-le-Preux

The day also saw the capture of Monchy-le-Preux by the infantry of the 15th and 37th Divisions, aided by six tanks. The capture of the village was an unbelievable feat of arms. Astonishingly, many of the attackers had lain out in the cold and snow for two days and it is a credit to their training and the fighting determination of the British Army that their attacks were pressed with such resilience. Despite the undoubted success of the infantry it is the the fate of the cavalry that Monchy has become synonymous with. With the village captured the cavalry were to advance east to the Green Line. However, they were forced back into the village by German machine gun fire where they were subjected to a ‘box barrage’ of artillery. Unable to escape, the narrow streets were clogged with horses and cavalrymen. The latter dismounted; seeking refuge in cellars but the horses could do nothing and were killed in great numbers as shells rained down. The streets of Monchy, full of horse carcasses and the foul residue of high explosive shells and animals are said to have run with blood.

Disaster for the Seaforths

An ominous taste of things for the future conduct of the battle to come was the attack by the 4th Division on the Green Line from Fampoux. At midday the 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers attacked from the sunken lane between Fampoux and Gavrelle . They were spotted whilst forming up by the enemy in Roeux and on the railway embankment and subjected to shellfire. At zero hour, as they advanced over a kilometre of open ground behind a feeble artillery barrage they were hit by heavy machine gun fire from the railway embankment and Chemical Works. The Seaforths attacked with 12 officers and 420 men and suffered casualties of all 12 officers and 363 men. Only 57 men survived this attack unwounded. This action and the casualties from other battalions of Seaforths are commemorated with the Seaforths Cross at Fampoux. Subsequent attacks were similarly costly. Roeux was fast earning a reputation as a fortress village. British attacks were badly planned and not supported by sufficient artillery fire whilst German defences grew in strength.

13 April was a day for fresh troops to take the field in order to carry on the attack. Exhausted and frozen men trudged back to Arras, replaced by units at full strength. By now it was almost definitely too late for the breakthrough that had appeared so possible on the evening of 9 April.

Infantry Hill – the destruction of the Essex Regiment & Newfoundlanders

An attack was planned from the precarious Monchy salient. Just two battalions of men would attack up Hill 100 (named Infantry Hill by the British). Conditions were so bad in the village with the detritus from horse carcasses blocking the narrow roads that the attack was postponed until 5.30 a.m. on 14 April. The plan was to capture Infantry Hill and send out patrols into the Bois du Sart and Bois du Vert to check for enemy. In hindsight this badly planned attack appears highly dangerous, almost suicidal. The Monchy salient was already surrounded on three sides by enemy forces. The attack, carried out by the 1st Essex Regiment and Newfoundland Regiment went in as prescribed. It started well and by 7.00 a.m. it was reported that Infantry Hill had been captured. However, in their first proper use of the new defensive employment of ‘elastic defence’ a German counter attack was delivered with such speed and precision that over 1000 Essex and Newfoundlanders were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. Monchy had been left undefended and was now at the mercy of advancing Germans troops. The situation was only saved by the commander of the Newfoundland Regiment, Colonel James Forbes Robertson who, with eight other men opened rifle fire from the edge of the village. For five hours their fire held back the enemy until fresh troops reached them. These men, known as the ‘Men who saved Monchy’ were all decorated for this action.

It is not the purpose of this brief article to mention every stage of the fighting but to merely pick out some of the more well-known points. Fighting continued on the Wancourt Ridge with the British capture of the remains of Wancourt Tower. Bitter fighting also continued in the Hindenburg Line; the most well-known casualty from these actions was war poet and officer on the 2nd Royal Welsh Fusiliers, Siegfried Sassoon who was wounded on 16 April. With limited piecemeal actions achieving little Sir Douglas Haig now took control, halting these costly and morale damaging attacks until a combined offensive could be made.

This decision marked the end of the first stage of the Arras fighting – the end of the First Battle of the Scarpe. It was now the turn of General Nivelle to launch his attack on the Aisne. After regrouping and with a marked improvement in weather the British attacked again on 23 April – the Second Battle of the Scarpe.

So, on 9 April 2012, ninety-five years after the whistles blew and attack commenced I will be raising a glass to the memory of the men of all nationalities who fought in the battle. Their sacrifice, perseverance and resolution to finish the job are astonishing. My respect grows for them daily. It is up to all of us to ensure that their efforts are not forgotten.

Should you be interested in the Battle of Arras then the book that Peter Barton and I produced, ‘Arras: The Spring 1917 Offensive including Vimy Ridge and Bullecourt’ is still available. I would urge anyone to visit Arras as it is a lovely town with good hotels and restaurants and only an hour’s drive from Calais. The battlefields are quiet and are immensely rewarding to visit. If you have a relative who fought in the battle or are looking for a guide to show you then please contact me. I would be delighted to help.

The Arras Tourist board are running a number of events over April 2012. Details can be found here: http://www.westernfrontassociation.com/attachments/article/2293/Arras_Ceremony_9_April.pdf

I spoke at the Thames Valley Branch of the Western Front Association (WFA) last Thursday (28 April). When first approached I had to choose between speaking about the Livens Large Gallery Flame Projector on the Somme or the subject of our last book, The Battle of Arras. I opted for the latter, mainly because I figured that the Channel 4 Time Team programme would have been only shown a short time before and so many of those attending would know at least the gist of the story. So, Arras it was. The talk was to last for about an hour (as it was, I think I spoke for nearer 70 minutes) and so this necessitated a good deal of reading to refresh the memory. I prepared a PowerPoint presentation to illustrate some aspects of the talk and managed to get panoramas to slowly scroll across the screen too (a technical feat I was quite pleased with!)

The talk was entitled “The Battle of Arras: April – May 1917? and was well attended with about 45 people regulars plus my brother Mark Banning and his friend and regular battlefield companion Malcolm Sime.

It was structured to not merely cover the battle but start with warfare in the Arras area in October 1914, look at the costly French actions of 1915 and then move on to British occupation in March 1916. The German attack against the 47th (London) Division on Vimy Ridge was touched upon and then I covered a basic backdrop to battle from the political and military standpoint and explained in detail the new German policy of ‘elastic defence’ to be brought into play for 1917. Moving through the Chantilly and Calais conferences I then spent some time on the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line (Operation Alberich) before exploring preparations for battle such as the tremendous work of the Royal Engineers. I also looked into French preparations, the actions of General Robert Nivelle and the extraordinary series of leaks and security lapses that marred the French pre-battle period. By this time half an hour had gone but I felt it important to set the scene fully and not merely delve straight into the battle itself.

It was structured to not merely cover the battle but start with warfare in the Arras area in October 1914, look at the costly French actions of 1915 and then move on to British occupation in March 1916. The German attack against the 47th (London) Division on Vimy Ridge was touched upon and then I covered a basic backdrop to battle from the political and military standpoint and explained in detail the new German policy of ‘elastic defence’ to be brought into play for 1917. Moving through the Chantilly and Calais conferences I then spent some time on the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line (Operation Alberich) before exploring preparations for battle such as the tremendous work of the Royal Engineers. I also looked into French preparations, the actions of General Robert Nivelle and the extraordinary series of leaks and security lapses that marred the French pre-battle period. By this time half an hour had gone but I felt it important to set the scene fully and not merely delve straight into the battle itself.

I structured the actual battle part of the talk by focussing on the First and Third Army fronts from north to south, starting with the Canadian Corps attack on Vimy Ridge before moving into what I always think of the main ‘Arras proper’ battlefield. Realising that no talk about the Battle of the Somme would neglect to work its way down the front line for 1 July 1916 I adopted the same structure – following each division’s success (or failure) as we moved southwards across the Scarpe and Arras-Cambrai road into Hindenburg Line territory until ending with the 21st Division at the south of the attacking frontage. Explaining the reasons for success in many sectors and failure in others I then worked my way through the battle focussing on stand-out actions. These included the capture of Monchy-le-Preux on 11 April 1917 and the destruction of the cavalry of the Essex Yeomanry and 10th Hussars in the village.

I also covered the attack by two battalions of the 10th Brigade (4th Division) towards the village of Roeux and the Chemical Works. 1/Royal Irish Fusiliers and 2/Seaforth Highlanders suffered grievous losses in the attack; the Seaforths attacked with 12 officers & 420 Other Ranks and their losses were all 12 officers & 363 O.R. This meant that a mere 57 men survived the action unwounded – and the objective wasn’t gained in any way. The beautiful Seaforths Cross on the Sunken Lane at Fampoux is a reminder of the men who attacked and suffered so much that day. I touched on the fighting at Bullecourt that day but felt that the disastrous actions around that particular salient village warranted a talk of their own.

The next attack to be looked into was the attack up Infantry Hill by the Newfoundland Regiment and 1/Essex Regiment on 14 April 1917 – an attack that almost destroyed both battalions and which left the way open for the German reoccupation of Monchy. The day was saved by a gallant band of men led by Lt Col James Forbes Robertson, CO of the Newfoundlanders who organised a small group of men to run to eastern buy discount ambien edge of village and open rifle fire. For five hours their fire held the Germans at bay until the village was relieved. All were decorated and became known as ‘The Men Who Saved Monchy’.

The next attack to be looked into was the attack up Infantry Hill by the Newfoundland Regiment and 1/Essex Regiment on 14 April 1917 – an attack that almost destroyed both battalions and which left the way open for the German reoccupation of Monchy. The day was saved by a gallant band of men led by Lt Col James Forbes Robertson, CO of the Newfoundlanders who organised a small group of men to run to eastern buy discount ambien edge of village and open rifle fire. For five hours their fire held the Germans at bay until the village was relieved. All were decorated and became known as ‘The Men Who Saved Monchy’.

I then worked through the month of April, looking at the failed French attacks on the Aisne and then explaining the movements of 23 April (Second Battle of the Scarpe) with particular emphasis on the fighting for Roeux and the Chemical Works by the 51st (Highland) Division. The battle was deteriorating against well organised and deployed German troops employing the new ‘elastic defence’ doctrine. It was a dreadful time – Third Army suffered 8,000 casualties alone on the 23rd/24th April.

It seemed apt giving the talk on 28 April as I then touched on the attack that day 94 years ago and the capture of the village of Arleux. It was building to the climax of battle – the Third Battle of the Scarpe on 3 May 1917 – a very dark day indeed for the British Army. The 21km frontage from Fresnoy in the north to Bullecourt (again) in the south lent itself to particular problems. The Australians at Bullecourt wanted a night attack to aid their chances of success – in the north this would have been disastrous for the attack on Oppy Wood. A miserable compromise was reached and Zero Hour was set for 3.45am – the attack was still to go in at night time. It was a terrible fiasco – many units were unable to even find their starting points and had no idea of direction to attack, merely following the direction of the artillery barrage with the hope of finding some Germans. Accounts mention morale being poor and a general malaise amongst the depleted attacking divisions. I read from the Official History: Military Operations France and Belgium 1917 by Cyril Falls as it summed up most eloquently the reasons for failure on 3 May 1917:

“The confusion caused by the darkness; the speed with which the German artillery opened fire; the manner in which it concentrated upon the British infantry, almost neglecting the artillery; the intensity of its fire, the heaviest that many an experienced soldier had ever witnessed, seemingly unchecked by British counter-battery fire and lasting almost without slackening for fifteen hours; the readiness with which the German infantry yielded to the first assault and the energy of its counter-attack; and, it must be added, the bewilderment of the British infantry on finding itself in the open and its inability to withstand any resolute counter-attack.”

I concluded with the finals stages of battle, the loss of Fresnoy and eventual capture of Roeux and the Chemical Works and for my last slide whilst talking about the men who had done the fighting I showed one of my favourite pictures. It shows a triumphant shot of a group of the 12/West Yorkshire Regiment in Arras celebrating their success of 9 April with captured booty. I was amazed when a man in the front put his hand up, saying he had spotted his grandfather in the photo! Apparently the only wartime souvenirs that his grandfather left were his medals and a copy of this photo. The man was 50496 Acting Corporal John Davison Johnson (marked with a red arrow in the photo) and I thank his grandson, John Johnson for this information – it quite made my night!

All feedback received has been good and the Branch Chairman, Bridgeen Fox, wrote very warmly afterwards with her thanks. Her comments can be read here. As she herself said, “it should have raised the profile of the battles of Arras and I hope it will have encouraged more people to explore the area”.

When I have some time I will write a blog piece with detail about the 3 May fighting. My thanks to Geoff Sullivan from the wonderful ‘Geoff’s Search Engine’ for furnishing me with some tremendous statistics for that day. If anyone is intersted in hearing this talk then please contact me. I am speaking on this subject in Bristol in October – see here for details. For those with an interest in the battle our panorama book on the subject is available here. Alternatively, if you are interested in a battlefield tour to Arras then please contact me – I would be happy to discuss.