Battle of Arras talk at 2013 Autumn conference of Worcestershire & Herefordshire WFA

On Saturday 19 October I will be speaking about the ‘The Battle of Arras – April/May 1917’ at the autumn seminar of the Worcestershire & Herefordshire Branch Western Front Association. The event will be held at the University of Worcester, Henwick Grove, Worcester, WR2 6AJ. Doors open at 12.00pm with my lecture starting at 1.00pm. Richard van Emden will be speaking at 3.15pm on ‘Boy Soldiers of the Great War’. Full details can be found on the attached PDF flyer. Please click to open and download: Worcestershire & Herefordshire WFA Seminar poster

Copies of ‘Arras – The Spring 1917 Offensive in Panoramas including Vimy Ridge and Bullecourt’ and Richard’s ‘Boy Soldiers of the Great War’ will be available to buy.

To buy tickets please call the Worcestershire & Herefordshire Branch on 01905 774797 or e-mail whb.wfa@hotmail.co.uk. The deadline for bookings has now been extended to 4 October.

I recently led a one day trip to the Arras battlefields for three generations of a soldier’s family (nephew, great-nephew and great-great nephew). I had been asked to research the actions of Private Horace Pantling, 10th Battalion Loyal North Lancashire Regiment around Arras. Horace’s Battalion formed part of 112th Brigade, 37th Division and will be forever known with the actions on 11 April around the small hilltop village of Monchy-le-Preux.

After a general briefing on the battle and a visit to the Carrière Wellington to take a tour around the underground system we headed out on the battlefield, starting on the British front line on 9 April 1917, the first day of battle. Following the arrow straight Arras-Cambrai road I explained the attack British assault up to the Brown Line near Feuchy Chapel. From then I was able to use a series of maps from the 37th Division files that showed positions of units every three hours for the first three days of battle. We followed the 10th Loyal North Lancs in their advance up the road in the early morning of 11 April. With the neighbouring 111th Brigade attacking the village of Monchy it was down to the 112th Brigade to take the Green Line to their right.

The Battalion war diary records that on moving to their assembly positions for the 5.30am advance the 10th Loyal North Lancs immediately were ‘met with very heavy Machine Gun and Shell fire’. However, their assault on the trenches around the La Bergère crossroads was successful and positions were consolidated. Casualties were estimated at 13 Officers and 286 men for the Battalion’s part in the opening stages of the Arras offensive. A number of the Battalion’s dead now lie in the nearby Tank Cemetery.

Tank Cemetery, Guemappe where many men of the 10th Loyal North Lancs killed on 11 April 1917 now lie

As we looked over the gently rising fields near Monchy it was hard to imagine the scene in the early morning of 11 April 1917. We had been blessed with a clear, spring day. The British troops who performed so magnificently that day 96 years ago did so with heavy snow and a chill wind across the battlefield.

Having been taken out of the line for a rest they were next in action on 23 April during the 37th Division’s assault on Greenland Hill during the Second Battle of the Scarpe. The war diary made grim reading with very little gain possible owing to the German occupation of the Chemical Works at Roeux on the right. On the 27th orders were received to attack Greenland Hill at dawn the next day. At 4.27am on 28 April that Battalion attacked and reached a trench that had been begun by the enemy. The war diary records that ‘By this time the Battalion had suffered heavily and only one officer was left’. Once more suffering from enfilade fire from the Chemical Works, the Battalion dug in. The attack was yet another failure in the face of superb German resistance.

28 April 1917 map of Greenland Hill overlaid on to Google Earth. Map taken from 37th Division War Diary, National Archives Ref: WO95/2513

It was during the actions on the 28th that Horace Pantling was killed. Horace, like so many British killed in the latter stages of the Arras offensive, has no known grave and is commemorated on the Arras Memorial. We were able to stand close to the positions where the 10th Loyal North Lancs assaulted and then, after a circuitous journey walk close to the spot where the Battalion dug in. It is one of those strange twists of fate that the junction of the A1 and A26 motorways now stands slap-bang right on Greenland Hill. Only by heading toward Plouvain and turning down a narrow track could we get close to the spot where the Battalion ended up. Sadly, the exact spot is now accessible only by driving on the slip road from the A1 to join the A26.

Arras Memorial where Horace Pantling and a further 35,000 servicemen from the United Kingdom, South Africa and New Zealand who died in the Arras sector between the spring of 1916 and 7 August 1918 are commemorated

We had visited Horace’s name on the Arras Memorial earlier in the day so it seemed a suitable place to end the tour. What struck me, as ever, was the small distances – easily covered in a minute or two in the car – that took so much effort to capture and consolidate in spring 1917. The British casualty figures for the Battle of Arras make sobering reading; 159,000 casualties in 39 days – averaging 4000 casualties per day. Despite countless visits to the battlefields such scale of loss in concentrated areas still both appals and moves me. Horace Pantling was one of those casualties but his name is certainly not forgotten and three generations of his family now know the ground over which he fought and was ultimately killed in April 1917.

“Thank you so much for organising such an excellent day in and around Arras last week. We all hugely enjoyed having your professionalism, enthusiasm and knowledge on tap, and your organisation was faultless! My father came away thrilled with the trip, and that was all I could have asked.” Nigel Pantling

A superb resource for those interested in the 10th Loyal North Lancs is Paul McCormick’s website http://www.loyalregiment.com/.

The internet is a wonderful thing; for anyone interested in a certain battalion or unit it is now possible to hammer a few key words into a search engine and find all sorts of information about their part in major, set-piece battles. Forums and discussion groups also have their place. Some regimental museums have even transcribed all of their battalion war diaries, making them available online for free.

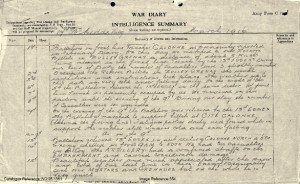

Extract from the 17th Middlesex Regiment War Diary. Reproduced with permission of National Archives, Ref: WO95/1361

Libraries, regimental archives and the National Archives all have information available to help understand events. However, what of the vast majority of time spent not going ‘over the top’ or taking part in the next ‘Big Push’? What of the less-well chronicled, monotonous but necessary routine of trench warfare?

It can be an immensely satisfying task to follow a unit’s movements around the battlefield; this is often undertaken as part of a family pilgrimage or greater desire to ‘follow in the footsteps’ of a relative who served. For me, when battlefield guiding, it is the part of the job that I love the most. Don’t get me wrong – I enjoy a general tour around the main tourist sites as well as the next person but it is in analysing the minutiae of war diary entries and working out such mundane things as billeting arrangements or where sports events were held that yields most fulfilment.

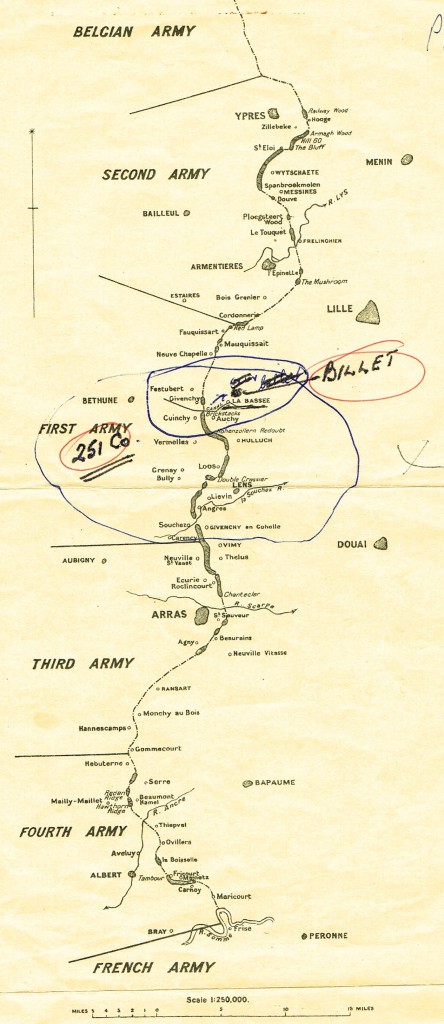

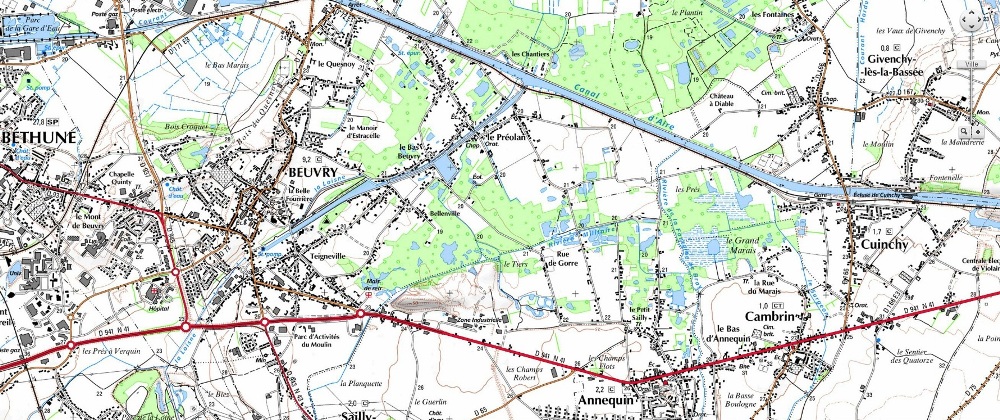

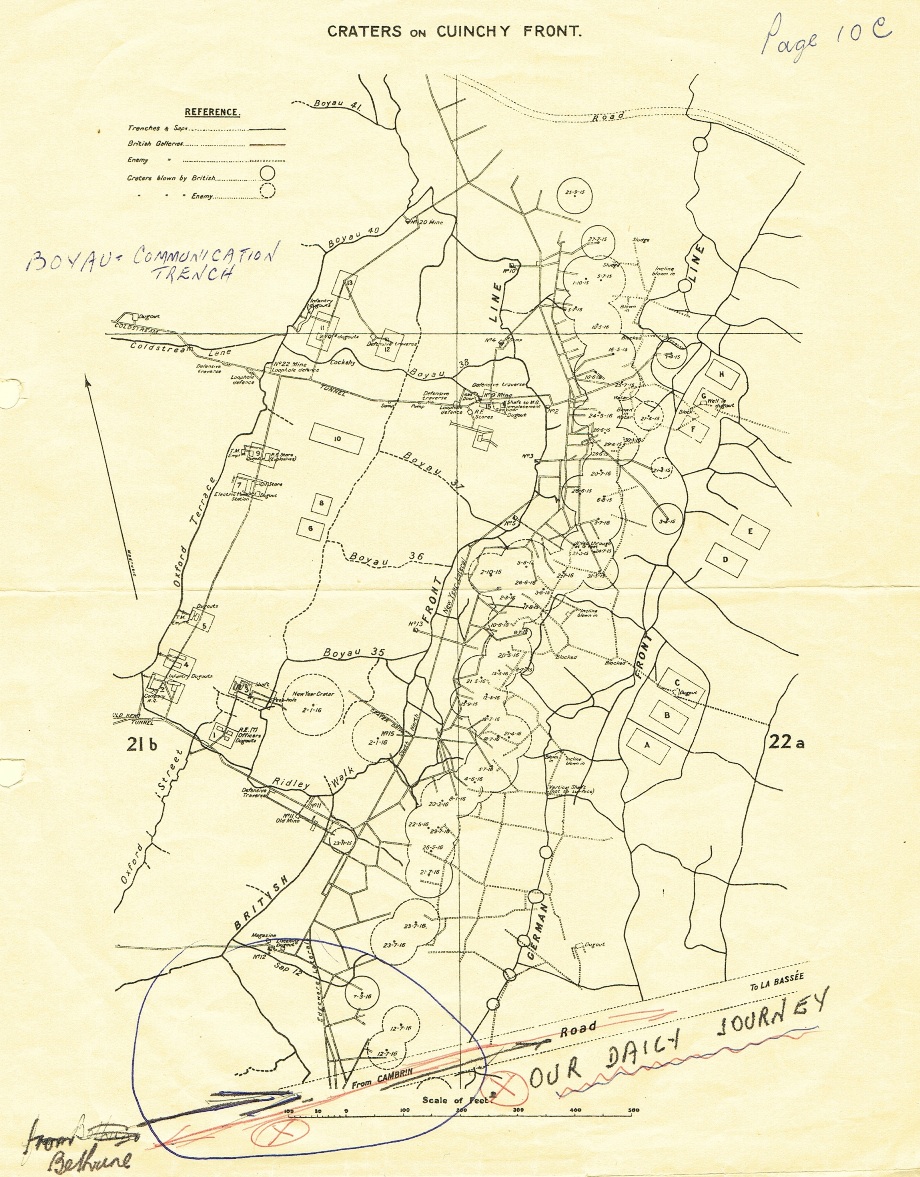

I recently returned from a bespoke trip following the 17th Middlesex Regiment (Footballers’ Battalion) around various villages and towns in French Flanders and the Gohelle coalfields in which they spent November 1915 – March 1916. My client’s grandfather had enlisted underage and spent four months with the battalion before being wounded in mid-March 1916; a wound which saved him from taking part in the Battalion’s action at Deville Wood on the Somme. During the four month period the Battalion held trenches at Cambrin, Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée and Festubert before taking over the Calonne sector from the French at the end of February.

Private James MacDonald, 17th Middlesex – first casualty of the battalion at Cambrin Churchyard Extension

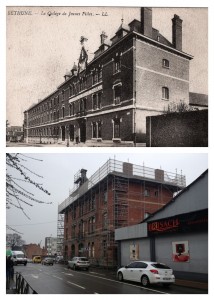

Over the course of our three day trip we visited all of these places, as well as many not associated with the 17th Middlesex; Fromelles, Aubers, Hulluch and Loos. Our stops were not solely restricted to places but included visits to 17th Middlesex Regiment men who had been killed in action. To stand at the grave of Donald Stewart (who served under the alias of Private James MacDonald) in Cambrin Churchyard Extension and know he was the first man of the battalion to be killed in action struck a particular chord. However, for me the highlight came during our visit to Béthune. The Battalion war diary for 2 December records a move to Béthune and billeting in the College des Jeune Filles. I had an old postcard of the college and knew the greater part of it still stood so arranged to visit it during our lunch stop.

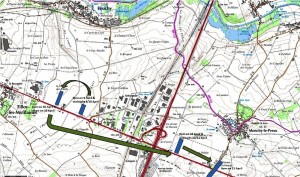

Battlefield guides will recognise the satisfying feeling – being able to tell someone that their relative was at that spot on a certain date, not nearby or somewhere in the town but here, actually here. We had the same feeling eating our lunch of ham and cheese baguettes in the square at nearby want to buy ambien online Beuvry. A poorly-attended market filled half of the square but, as we sat eating, I was able to explain that this village, now almost a suburb of Bethune was where the Footballers’ Battalion had spent Christmas Day 1915. There was no plaque commemorating this event, no visible link at all, just the knowledge that men of the Battalion would have walked around the square over the festive time, amongst them my client’s grandfather. It made the lunch, eaten in the car whilst a steady drizzle fell that bit more special.

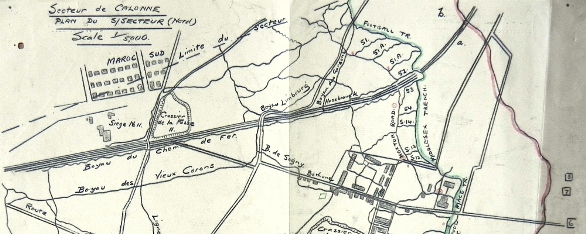

After a tour around the Loos battlefield I took my client to the site of Middlesex and Football Trench in the Calonne North sub-sector. It was here in that his grandfather was wounded in March 1916. The war diary of the 16th records ‘4 casualties occurred from GRENADES, 2 in “B” Coy and 2 in “D” Coy’; it is likely that my client’s grandfather was one of those wounded men as he left France on the 18th, crossing the channel for treatment at a hospital in Britain. Such were the effect of the wounds received that he was discharged from service three months later. Compared to many who served, his war was unremarkable – his service record shows he played no part in any major offensive and yet the four months he spent with the 17th Middlesex from November 1915 – March 1916 had a profound effect on him for the rest of his life.

Map of Calonne North Sector showing Football and Middlesex Trenches . Reproduced from 6th Infantry Brigade War Diary held at National Archives, Ref: WO95/1353

Calonne North map overlaid on to Google Earth. Football Trench runs between the A21 motorway and the Lens – Bethune railway embankment.

Football Trench ran through what is now an open field next to the A21 motorway and the urban sprawl of miners’ cottages of Liévin. The railway line from Lens to Bethune runs across the northern tip of Middlesex Trench. Much of the rest of it is hidden under a civilian cemetery or is being built upon for new housing. A casual visitor to the site today would find it far from enchanting. Locals stared at our car with British number plates; clearly, the back streets of Liévin didn’t see too many battlefield tourists. However, the relative inaccessibility of the spot made visiting it that bit more special. To those of us in the car, it felt as though we had tracked down a site rather than merely followed the tourist signs. Having researched the young Middlesex soldier it certainly had an effect on me. It was a real pleasure to be able to share these places with his grandson; not just the obvious sites of front line and communication trenches but the places in he was billeted, the towns and villages he would have known well and the roads he marched along on his route to and from the front. To me, this is what makes following in a soldiers footsteps such an enriching experience.

N.B. A very readable account of the 17th Middlesex Regiment is Andrew Riddoch & John Kemp’s ‘When the Whistle Blows: The Story of the Footballers’ Battalion in the Great War’ – highly recommended.

Following in the footsteps of the 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade at the Battle of Arras (April – May 1917)

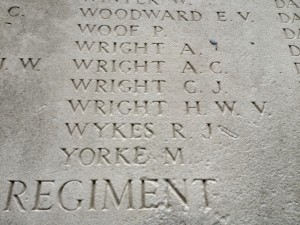

Earlier this month having spent a few days recceing sites and walks for upcoming trips I spent a day showing a client, Tony Wright, around the Arras battlefields following in the footsteps of his great uncle, S/30401 Rifleman Herbert William Victor Wright, 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade who was killed on 3 May 1917. It was most likely that Herbert had joined the battalion as one of nearly four hundred reinforcements received in January 1917. As such, the spring offensive at Arras would be his first major battle.

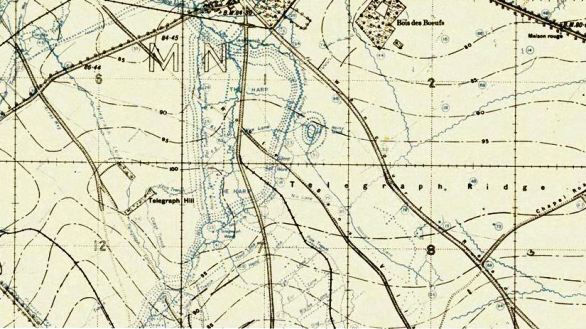

Sadly, Herbert Wright’s service record no longer existed and so we were unable to determine which company he had served in. However, with the knowledge that he would have been ‘in the area’ we started off by looking at the battalion’s role in the 9 April attack. The 9th Battalion Rifle Brigade was part of 42nd Infantry Brigade, 14th (Light) Division. The divisional objectives for 9 April were to capture the strong German position known as the Siegfried Stellung, (Hindenburg Line) which the Germans had fallen back to throughout the month of March. The hinge of the ‘old’ German line and new Hindenburg Line was the village of Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines. South of the village lay the 14th Division’s objective, the southern part of The Harp, a formidable position some 1000 yards long and 500 yards wide, full of tangled field defences. Along with Telegraph Hill to its immediate south its dominant position enabled German defenders to fire in enfilade northwards up Observation Ridge and southwards to Neuville Vitasse; its capture was absolutely critical.

Looking across the rising ground of The Harp. The 9th Rifle Brigade advanced across here on 9 April 1917

The role of the 9th Rifle Brigade on 9 April was limited to that of ‘moppers-up’. An initial assault was to be made against the southern portion of ‘The String’, a trench running down the length of The Harp, by the 5th Ox and Bucks Light Infantry and 9th King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Once captured the 5th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry would then pass through or ‘leapfrog’ the two battalions to capture the second objective close to the Blue Line running south from the rearward face of The Harp down the Hindenburg Line. Nearly seven hours after the initial advance and with these objectives taken B & D Companies of the 9th Rifle Brigade, under the command of Captain Buckley were to leave their positions in and around the old German front line to clear the ground between the Blue and Green lines within the Brigade boundaries.

They would also occupy an outpost line north east of the Tilloy – Wancourt road (now the D37). Considering the magnitude of the day’s fighting the Battalion war diary gives scant information about the work completed other than to record the final objective was gained by 1.30pm with one hundred prisoners and two machine guns captured. Casualties sustained were Captain D.E. Bradby killed , 2/Lt H.M. Smith wounded and fifteen Other Ranks wounded. Despite differing figures from those provided in Brigade records it is clear that losses amongst the 9th Rifle Brigade were extremely light when compared to other battalions within 42nd Brigade.

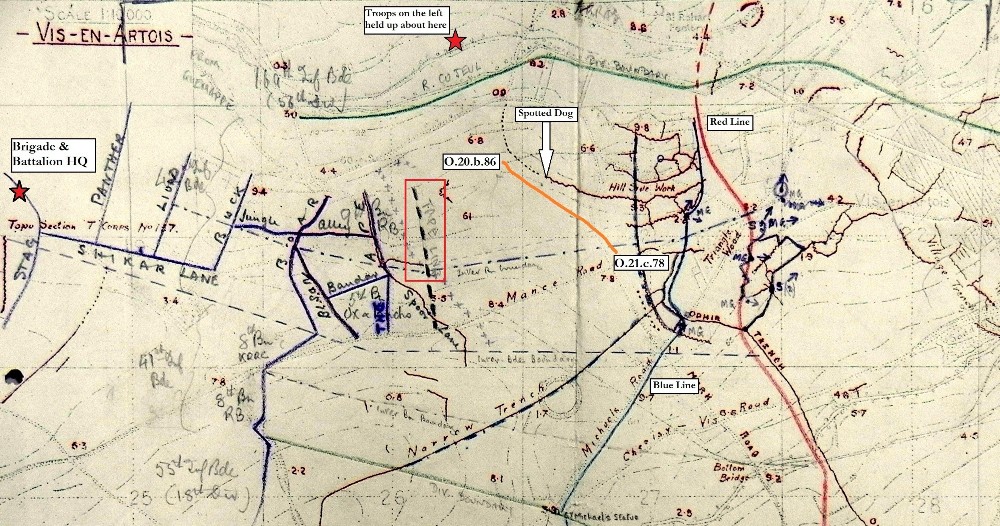

After relief on 12 April the Battalion spent time in training where they received a draft of fifty two reinforcements. On 23 April the Battalion began their march back to the battlefield, moving into newly captured positions between Guémappe and Chérisy on the evening of the 24th. The war diary records constant shellfire for this entire period; on one day alone 2/Lt J.M. Harper and a further sixteen Other Ranks were wounded. Between 30 April – 2 May the Battalion were in reserve but provided working parties to dig out a new communication trench named Jungle Alley running between the Ape and the Boar trenches before taking up their positions in the front line north of Chérisy on 2 May. The stage was set for a renewal of the offensive; three armies would be attacking along a fourteen mile frontage from Bullecourt in the south to Fresnoy in the north. Having suffered such comparatively small losses on 9 April the 9th Rifle Brigade was to take a leading part in the coming battle, attacking on the left of the Brigade next to the 5th Ox & Bucks Light Infantry. The 5th King’s Shropshire Light Infantry and 9th King’s Royal Rifle Corps were in Brigade Reserve.

The decision to launch the attack at 3.45am in darkness was contentious. Many commanders protested to no avail. A further complication for the 9th Rifle Brigade was their position nearer to the enemy than neighbouring units. As such, they were not to advance from their jumping off line until eighteen minutes after Zero Hour. The Battalion had two objectives; firstly to capture the Blue Line running in front of Triangle Wood and through Hill Side Work and then to push on to the Red Line, completing the capture of both positions. Advancing from a line 150-200 yards east of the front line marked by white tape fixed to the ground, the Battalion was to advance behind a ‘creeping barrage’ of artillery shells exploding in a slowly moving curtain across the battlefield.

Ten minutes before Zero Hour the first wave left the assembly trenches to line up on the tape. At 4.03pm they advanced, followed by the second wave that left the assembly trenches at Zero +42 minutes. In common with many units who attacked that dreadful day, no further report was ever received from the companies in the first wave. German artillery fire was extraordinarily heavy (lasting for over fifteen hours) with eight company runners either killed or wounded. Post -action reports noted the first wave veered to the right in the darkness, striking a new German trench wired and held by the enemy. Despite this, it was captured by Zero + 40 minutes and advance progressed. However, enfilade machine gun fire caused heavy casualties and ‘few, if any ever reached the rear of Hill Side Work’. All eight officers of the first wave became casualties very early in the day, some being wounded several times. Only seven NCOs of the first wave ever returned. The second wave fared no better. As their advance was in daylight they were subjected to machine gun fire sooner than the first wave and also came up against machine gun positions which had been established after or missed in the dark by the first wave, in addition to enfilade fire from across the Cojeul valley near St Rohart’s Factory.

Cross left in memory of Herbert Wright, 9th Rifle Brigade. Triangle Wood and Hill Side Work are on the horizon

The second wave was finally held up just in front of Spotted Dog Trench which was held by the enemy; they dug in along a line of shell holes about 600 to 700 yards in front of their original front line at Ape Trench. A German counter-attack against the 18th Division who had captured Chérisy forced their line back to its starting position; this action rippled northward with orders sent out to recall the Battalion. Such was the dominance of German artillery and machine gun fire (firing continuously from both flanks and from across the river valley) that these orders could only be communicated to two platoons; it being impossible to contact the remnants of the battalion occupying shell holes close to Spotted Dog Trench. On the evening of the 3rd two patrols were sent to recall one company holding a line of shell holes and strong point close to the German trench. Over the next couple of nights survivors of the 9th Rifle Brigade’s attack returned to the original British line. The Battalion’s casualties during the day’s operations were 12 officers and 257 Other Ranks. The 9th Rifle Brigade was relieved on 4 May before heading back to The Harp. This disastrous day marked the beginning of the end of the Battle of Arras. Desperate fighting continued for possession of Roeux, its infamous Chemical Works and Greenland Hill plus around Fresnoy which was recaptured on 8 May. However, by then British attentions were turning northwards to Flanders.

As Herbert Wright’s company is unknown it proved impossible to know whether he formed part of the first or second wave of attackers. Tony and I we walked the attack, passing the assembly trench positions, taped line from which the battalion advanced before moving to the final positions reached. It was here that Tony laid a small poppy cross in memory of his great uncle. Herbert Wright was one of ninety seven men of the Battalion killed on 3 May; all but two are commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the Missing. We visited the Arras Memorial and saw Herbert Wright’s name on Panel 9.

His remains may be buried in the grave of an unknown soldier or still be out on the battlefield. The Third Battle of the Scarpe, as the fighting over 3/4 May was named, was an unmitigated disaster for the British Army which suffered nearly 6,000 men killed for little material gain.

In the Official History, Military Operations France and Belgium 1917 Cyril Falls gives the following reasons for the failure on 3 May 1917 in the VII Corps frontage:

“The confusion caused by the darkness; the speed with which the German artillery opened fire; the manner in which it concentrated upon the British infantry, almost neglecting the artillery; the intensity of its fire, the heaviest that many an experienced soldier had ever witnessed, seemingly unchecked by British counter-battery fire and lasting almost without slackening for fifteen hours; the readiness with which the German infantry yielded to the first assault and the energy of its counter-attack; and, it must be added, the bewilderment of the British infantry on finding itself in the open and its inability to withstand any resolute counter-attack.”

This stark paragraph illustrates perfectly the battlefield during the 3 May 1917 fighting; nightmarish, terrifying and bloody. Having been at home for a week now I am still thinking about it and the windswept ridge between Guémappe and Vis-en-Artois.

“I spent an extraordinary day with Jeremy walking in the footsteps of my Great Uncle, who fell on May 3rd 1917 at the Battle of Arras. He did a wonderful job of balancing a very good explanation of the complexities of the overall battle itself with a highly emotional and personal end to the day of literally experiencing his final hours. As my Great Uncle was a private soldier, without detailed records of his service easily available, I was deeply impressed by how he brought together a range of different sources to nevertheless give me a really specific and personal understanding of what he and his comrades went through. It was an absolutely unforgettable experience”. Tony Wright

A good write up of the part played by one young officer, 2/Lt William Clarke Wheatley, former pupil at Sandbach School who was killed in the 3rd May attack can be found on Conor Reeves’ excellent website: http://sommejr.wordpress.com/william-clark-wheatley-3517/.

A look back: 2012 in review

It has been another busy year on the battlefields. The year started with the BBC’s broadcast of Sebastian Faulks’ WW1 novel, Birdsong which acted as a catalyst for generating people’s interest in tunnelling and underground warfare. Back in June 2011, prior to filming we had taken actors, Eddie Redmayne and Joseph Mawle underground at La Boisselle to show them the real environment of a WW1 tunneller. Most of the year has been spent in organising and running our current archaeological project at La Boisselle. In total we worked five weeks on site, ranging from a few days in March to an entire fortnight of work in May and October. Details of the work can be found on http://www.laboisselleproject.com/ and our BBC Four documentary will be broadcast sometime in January. A personal highlight was our time filming underground in October. Descending a 50ft shaft down to the labyrinthine galleries at the 80ft level and exploring 700ft of tunnels, the first people to do so in over 96 years, was an incredible privilege and one which I will certainly never forget.

We opened the site from 30 June – 2 July, welcoming over a thousand visitors who were on the Somme for the 1 July commemorations. In the past I had always kept away from the Somme for this period and so had not experienced the crowds but found it hugely satisfying to see the public reaction. Best of all was the opportunity to fly over the battlefield in a friend’s helicopter which was infinitely safer than the microlight I had been up in during May’s dig!

July's helicopter flight gave the opportunity to see the battlefield from an entirely different perspective - here is Caterpillar Valley Cemetery looking east to Longueval and Guillemont

I have spoken to many groups about La Boisselle this year; at schools, various WFA branches, Great War societies, private dinners and at Eastbourne Redoubt (as part of their Great War lecture series). Most recently, it was a thrill to speak in the Officer’s Mess at Sandhurst to ninety guests who had joined us for a fundraising dinner. However, my hardest lecture to give was in Arras in April, almost ninety five years to the day that battle had commenced, when I spoke about the April- May 1917 offensive for an hour….in French.

As a result of these other commitments I spent little time on the rest of the battlefields, taking only a few guided tours – trips to Arras and the Somme in the spring and autumn were a particular highlight. In October I spoke on BBC News and the Jeremy Vine show on BBC Radio 2 on the Government’s First World War Centenary plans for 2014-18. Over £50m has been allocated to commemorate the centenary but as much of this is designated for the IWM’s revised WW1 Gallery, financially it really is a drop in the ocean. It will be interesting to see the effect of this governmental effort on battlefield visitors and a greater understanding of the war, both at home and abroad.

My work with schools continues to grow and the autumn saw me providing talks and workshops for a number of classes. I am now part of Bristol’s ‘Heritage Schools’ programme provided by English Heritage and have a number of workshops already booked for the coming year.

In January I spent three days filming with actor and comedian Hugh Dennis for the BBC’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’, following Hugh’s grandfather from Arras up to Ypres and Wytschaete. The resulting episode was broadcast in September. The following month I worked with Yellow Duck Productions on their BBC Wales’ ‘Coming Home’ programme with actor Robert Glenister, explaining his relative’s service in the AIF and part in the disastrous attack at Fromelles in July 1916. I was also interviewed for a programme on gas and flamethrowers for History Channel USA to be broadcast in 2014.

The coming year is already looking busy with a number of bespoke battlefield trips booked, plenty of research projects agreed for clients, and research work beginning on a new BBC television commission. I am also planning on spending time over the winter months on recces and battlefield walking and, as ever, will post images and updates on my Twitter account. Please check out 2012’s blog entries for more information on some of the events mentioned.

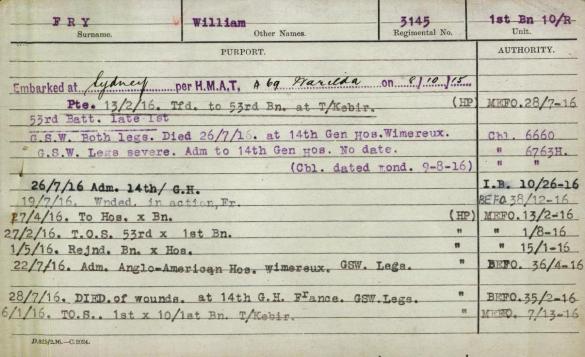

Private William Fry, 53rd Battalion AIF at Fromelles for BBC Wales ‘Coming Home’ with Robert Glenister

In October I was approached by Yellow Duck Productions to help with an episode of their BBC Wales series ‘Coming Home’. I was to conduct research into the wartime service of William Fry, a miner from Penclawdd in the north of the Gower Peninsula outside Swansea. William Fry was a relative of Spooks and Hustle actor Robert Glenister.

Talking through William Fry's wartime service with Robert Glenister in St Gwynour's Church, Penclawdd

William Fry left Wales in 1914, en route to a new life in Australia. At sea when war was declared, he arrived in Sydney in late August 1914. By the end of July 1915 William had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force and sailed from Sydney on 8 October 1915 bound for Egypt. Whilst at Tel el-Kebir in February 1916 he transferred to the 53rd Battalion, a strange mix of Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion and new, inexperienced reinforcements from Australia. The battalion, along with the 54th, 55th and 56th formed the 14th Infantry Brigade, part of the Fifth Australian Division.

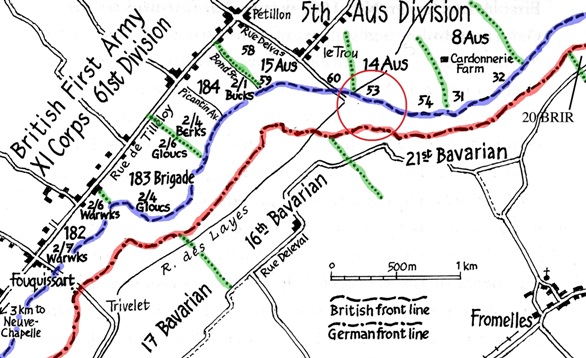

The battalion arrived in Marseille at the end of June and after a journey north through France entered front line trenches opposite Fromelles on 10 July. It was customary practice to provide new units with time to ‘bed in’ in a quiet, nursery sector in order to get used to the routines and peculiarities of trench life. No such luxury was afforded William’s 53rd Battalion as, within a week, they were selected to be at the vanguard of a strong attack against German trenches at Fromelles. After a day’s rest in billets the 53rd Battalion were back in the front line on 17 July.

Map showing frontage for the Fromelles attack. The position of William Fry’s 53rd Battalion AIF is circled.

The plan required an initial softening of German defences by artillery bombardment and the attacking infantry to advance at 1800hrs in broad daylight, capturing and seizing two lines of trenches. At 1743hrs the first wave moved out into No Man’s Land, followed 100 yards later by the next wave. At Zero Hour (1800hrs) the Battalion charged and captured the first two lines of trenches as planned but then, contrary to the agreed plan, pushed on ‘200 yds further to hold back enemy’s bomber who were counter-attacking’.

Members of William Fry’s 53rd Battalion prior to ‘hopping the bags’ on 19 July 1916. Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial (ID Number A03042).

The positions were held through the night but determined German counter attacks coupled with an exposed right flank forced the 53rd back across No Man’s Land to their starting position at 0930hrs on the 20th. Casualties for the operation totalled 625, an extraordinarily high figure which included the commanding officer. The attack at Fromelles was a complete disaster; losses for the Fifth Australian Division were over 5500 men. At some point on the 19th July William Fry was badly wounded; his medical records show he received GSW (Gun Shot Wounds) to both legs. He was evacuated along the casualty clearance chain, ending up at No.14 General Hospital at Wimereux on the channel coast. Sadly, William Fry died of his wounds at 4.15pm on 26 July 1916 and is buried at Wimereux Communal Cemetery.

Extract from William Fry’s service record showing his movements from leaving Sydney in October 1915 to his wounding on 19 July and death at No.14 General Hospital, Wimereux.

Prior to the day’s filming at St Gwynour’s Church in Penclawdd Robert was completely unaware of this part of his family’s history. Using the Battalion war diary and maps I was able to talk through William’s service and the 53rd Battalion’s attack on Fromelles. In many ways it was a typical example of the global scale of the war. A miner, all 5ft 2 ¼ inches of him, seeking a new life in Australia but enlisting for King and Country and travelling all the way back to Europe to do ‘his bit’. Fromelles was an ill-conceived diversion against tactically superior German forces but this should not detract from the endeavour, patriotism or simply a longing for involvement in the war of William Fry and his mates in the 53rd Battalion AIF. It was especially poignant leaving the church and walking up the path to my car. It is lined with lime trees – replacements for the original trees planted in the 1920s to commemorate local men lost in the war.

Robert Glenister gave an interview to Wales Online about his participation in ‘Coming Home’: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/showbiz-and-lifestyle/television-in-wales/2012/12/08/hustle-star-robert-glenister-on-his-welsh-ancestor-s-wartime-heroism-91466-32377072/

School workshop at Putney Park School

On 22 November I gave a workshop at Putney Park School in south west London. It was a fascinating day speaking to children ranging in age from six to fourteen. The morning was devoted to Juniors who had got into the swing of things by dressing in Great War era clothes for the day. One girl was wearing a genuine nurse’s outfit from the time. The day started with an hour’s talk on what it was like to be an infantry soldier, why men enlisted and how they did so, information on their training and then an hour-by-hour breakdown of a typical 24 hour period spent in the trenches.

After a tea break we boarded a coach that took us to the nearby Richardson Evans Memorial Playing Fields War Memorial, situated in a five-acre area of landscaped ground. It commemorates men with Putney and Wimbledon connections; in consequence the memorial has many names. The children looked at these and I pointed out men with decorations (three Victoria Cross recipients alone) and those with the same surname; sadly the memorial contains many sets of brothers. The trip was based on trying to encourage the children to see not just a list of names but that every individual had a story whose death had left a loved one heartbroken and bereft. After laying a specially (and rather lovingly) crafted wreath followed by a minutes silence and the Exhortation we returned to school.

I was then able to provide details on some of the men listed on the memorial including Zeebrugge Raid hero, Lt Commander Arthur Harrison VC. I had found one local family, the Nottingham’s, who had lost three brothers in the space of a year. Interestingly, each brother had fought in a different unit or service. I traced the family back to the 1881 census and was able to show how the family moved around and grew – there were seven children in total – before the war claimed the lives of three. The first to be killed was Leslie, a Gunner in the Royal Marine Artillery who was serving on HMS Queen Mary when it was lost at Jutland on 31 May 1916. The next boy lost was Arthur, a Sergeant in the 3rd Battalion Canadian Infantry. He had emigrated to Canada before the war in search of work and, like so many other British in Canada at the start of war, had enlisted in the Canadian Army. He was badly wounded on the Somme on 9 September and two weeks later succumbed to his wounds, being buried in Wandsworth (Earlsfield) Cemetery. The final boy to die was Ernest, the eldest of the family and a decorated sergeant in the Civil Service Rifles. He was killed on 10 June 1917. Using archival material I was able to show details of the brother’s service and, where possible, mention of them by name in battalion war diaries.

I finished my talk by speaking about Private Alfred Whittle, 10th Battalion Sherwood Foresters who was killed outside Ypres just after Christmas 1915. What made him special to the children was the fact that the CWGC recorded his daughter Alice lived at 7, Woodborough Road in Putney – part of what is now the school complex. I hoped that by picking specific names and elaborating on their story the children would realise that the list of names were once living, breathing human beings with families that loved them and mourned their passing.

The three 'Nottingham' brothers on the Richardson Evans Memorial Playing Fields War Memorial. Arthur, Ernest & Leslie all died within a year of each other.

After lunch I spoke to Year 1 children about the census and what sort of things are recorded before finishing off with an hour’s lecture to Year 9 students on the life of an infantry soldier. My thanks to Mrs Wright for arranging the day, staff members for their welcome and the children for their enthusiasm and interest.

“Jeremy’s knowledge, professionalism, charisma and palpable enthusiasm for everything to do with World War 1 not only brought the topic alive for my students but changed the lives of many of us. In such a short time we fully understood trench warfare and the impact on families and nations. From the first time I made contact with Jeremy he responded quickly to my queries, offered fantastic ideas and prepared very well for the day. I simply would not teach the topic again without him.

In addition, after his visit I had enough material for the next four weeks for class work. The children steered their parents to find out more about their relatives using the strategies Jeremy taught. One has since visited the National Archives, read about her great grandfather in the war diaries and then researched the three battles he fought in, all of which Jeremy had mentioned. Another pupil researched her great grandfather by emailing relatives and was proud to bring in a number of items from his uniform and life. Jeremy’s idea of visiting a memorial and researching some of the names on there really brought it home to the children and I know that on Armistice Day, and probably every day, my children will really be remembering our men. Jeremy spent the morning with our year 5s and 6s and then did two wonderful presentations to year one and nine. I cannot recommend him highly enough.”

Mrs J. Wright, Head of Junior School, Putney Park School

Earlier this month I finished an extraordinary week’s work at La Boisselle followed by four days guiding a group of writers around the Somme and Arras battlefields. Last year I had taken Vanessa Gebbie on a bespoke tour following in the footsteps of the 14th Battalion Welsh Regiment (Swansea Pals). She had been extolling the virtues of the battlefields ever since and had cajoled other writers to join her for a few days away.

Somme

After picking up my passengers and hire car in Lille we headed south to the Somme. Our first port of call was to the Glory Hole at La Boisselle where I was able to take my group underground. BBC News were covering our work on site that day and it was exciting to stand at the top of W Shaft and hear the filming taking place below for that night’s Six O’Clock News. Vanessa has written about this on her blog here. After a visit to the Lochnagar Crater we stopped at Becourt Military Cemetery and Norfolk Cemetery en route to our comfortable accommodation at Chavasse Farm, Hardecourt-aux-Bois.

“I can’t tell you what an amazing time I had on our trip. You are a natural – to call you either a historian or a tour guide is to miss the point entirely, I think. You brought it alive for us, you animated the land, the people, the history, in a way I don’t think I’ve ever experienced. There wasn’t one minute when you were talking where I was bored, where I zoned out. You made me want to know everything. And more than that, you inspired me to think about identity, nationality, what I might be prepared to die for.” Tania Hershman

The next day was spent on the Somme starting in the southern sector at the junction of British & French forces between Maricourt & Montauban. Stops that morning included Suzanne Communal Cemetery Extension to visit the graves of 18th Manchester Regiment men killed in May 1916 when German mortar fire blocked their mine shaft at Maricourt, the Carnoy crater field where I explained about the use of the Livens Large Gallery Flame Projector on 1 July 1916, Devonshire Cemetery at Mametz and then down to the impressive Red Dragon of the 38th (Welsh) Division Memorial at Mametz Wood. Despite heavy rain most of us had a walk up the slope from Death Valley to look at positions occupied by the 11th South Wales Borders and 16th Welsh in their unsuccessful 7 July attack on the Hammerhead. After a coffee and change of clothes we headed back out. Stops included Guillemont Road Cemetery, High Wood and the Nine Brave Men (82 Field Company RE) memorial in Bazentin-le-Petit before lunch at Old Blighty Tea Rooms, La Boisselle.

The remains of the afternoon was spent at Aveluy Communal Cemetery Extension, Mash Valley and the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme before stopping at Flatiron Copse Cemetery, Mametz on our way back.

Over dinner that night I learnt one of my party had a relative with the 3rd Coldstream Guards who had been killed in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette on 15 September 1916. Our first stop the next morning was on the road between Ginchy and Lesboeufs to look at the starting positions for the attack. Guardsman Ernest Saye is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial so there was a chance his remains were still lying in the fields before us.

We paid our respects at the Guards Division Memorial, Lesboeufs before a stop specifically requested by Vanessa at Morval British Cemetery. This quiet spot contains 38th (Welsh) Division casualties killed in the capture of Morval on 31 August/1 September 1918. After stops at the Cedric Dickens Cross and Delville Wood Cemetery & Memorial we headed north of the Roman Road to Thiepval to pick up where we had left off the previous day. Stops included the Ulster Tower Newfoundland Memorial Park, the Sunken Lane at Beaumont Hamel and then over the Redan Ridge for a picnic lunch in the majesty of at Serre Road Cemetery No.2 where the Somme part of our tour ended.

Arras

En route north we stopped at Ayette Indian & Chinese Cemetery before arriving at Neuville-Vitasse Road Cemetery, Neuville-Vitasse where I set the scene for the Arras offensive. The elevated position offers a fine viewpoint from which to show the southern sector of the battlefield with Monchy-le-Preux, Henin Hill and the route of the Hindenburg Line clear to see.

Poring over maps of the Arras battlefield at Neuville-Vitasse Road Cemetery. Thanks to Vanessa Gebbie for her permission to use this image.

After a visit to Cojeul British Cemetery to pay our respects at the grave of two Victoria Cross winners, Private Horace Waller and Captain Arthur Henderson we headed up to the open windswept ground of Henin Hill where we had a good look around a surviving German ‘mebu’ concrete pillbox, part of the Hindenburg Line defences in the area. After repeatedly getting in and out of the car we were keen to stretch the legs and so took a walk to Heninel-Croisilles Road Cemetery where I read the poet Siegfried Sassoon’s account of being wounded nearby. We then walked down to Rookery Cemetery and Cuckoo Passage Cemetery.

Our next stop was on Wancourt Ridge outside Wancourt British Cemetery where I read John Glubb’s detailed account of the bridging work undertaken by 7 Field Company RE across the River Cojeul in the valley before us on 23-25 April 1917. The landscape is wonderfully easy to match up to Glubb’s descriptions and offers the chance to imagine the scene 95 years ago. Afterwards some of us walked up to the site of Wancourt Tower. Our final stop of the day was the rarely visited but rather beautiful Vis-en-Artois Memorial. One of our party Caroline had a relative commemorated on the panels. Percy Honeybill, 1st King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment) was killed on 2 September 1918 attacking the Drocourt- Quéant defences.

Our final day saw us head to Arras for a croissant and coffee breakfast in the Petite Place before a visit to the Arras Memorial to the Missing and Faubourg-d’Amiens Cemetery. We then headed out along the Arras-Cambrai road to find the spot between Guémappe and Cherisy where Third Army Panorama No. 556 was taken on 6 May 1917. Standing close to the spot where the image was taken it offers an ideal opportunity to visualise battlefield conditions in May 1917. Our next stop was at Kestrel Copse to see the new cross for Captain David Hirsch VC. We then headed north to Monchy-le-Preux where I explained the magnificent action which resulted in the capture of the village on 11 April 1917. One of our party’s grandfather had served in the Essex Yeomanry. I was able to show her Orange Hill and the fields which her grandfather would have galloped across on 11 April 1917. We then headed up Infantry Hill where I told of the disastrous Newfoundland and Essex Regiment attack on 14 April and the subsequent action by the “Men who saved Monchy”.

Crossing the River Scarpe to Roeux, we visited the site of dreaded Chemical Works, now a benign Carrefour supermarket and garage. I always find it a pity that there is nothing on the site to show the ferocity of the fighting here in April and May 1917. Lunch was taken in Sunken Lane Cemetery at Fampoux (written about here by Vanessa Gebbie ). We discussed the terrible fighting for Roeux and the 11 April attack by the 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers. After visiting Gavrelle we headed north to Vimy Ridge, visiting the trenches and Walter Allward’s masterpiece, the Vimy Memorial where we bumped into my brother Mark guiding a group. What a small place the battlefields are sometimes! There followed an interesting journey back to Lille Europe station where the car was returned in a rather muddier state than it had been when picked up.

My thanks to Vanessa, Tania, Zoe, Angela and Caroline for being such good company and making the trip such a delight. I am already planning the itinerary for 2013!

“Thank you is really an inadequate word to convey my feelings about the weekend. I still feel as if I’ve been to a different place and had my life changed. I’m not quite sure how you managed it but it felt as if you really took us back in time to 1914, 1916, 1917 and 1918 and that we were standing alongside the men waiting for the whistles to send them over the top and later dragging or rolling themselves back to the safety of their trenches. I thought I knew a bit about the First World War having done a history degree and having read the poetry. At an intellectual level I suppose I did know about the war but emotionally I had no idea what it was like for the men and that experience was what you gave us with the maps, the panoramas and all the stories. Over the last few days they lived and breathed again. It’s difficult to pick out my favourite moments as everything felt like a highlight. I can’t remember if it was Tania or Zoe who said they’d never before come across a guide who didn’t bore them for a second. Actually ‘guide’ isn’t the right word – the ‘expert’ comes closer but also the ‘enthusiast’ brimming over with things you wanted to share.” Caroline Davies