Posts Tagged ‘Lincolnshire Regiment’

A raid with severe repercussions: the mutilation of 8th Lincolns dead at Ghissignies, 2-3 November 1918

In the course of research for a client whose relative had served in the 13th Battalion Royal Fusiliers I was reading the unit war diary when the following passage, taken from 11 November 1918, the day the armistice came into effect, stopped me in my tracks:

11 November 1918

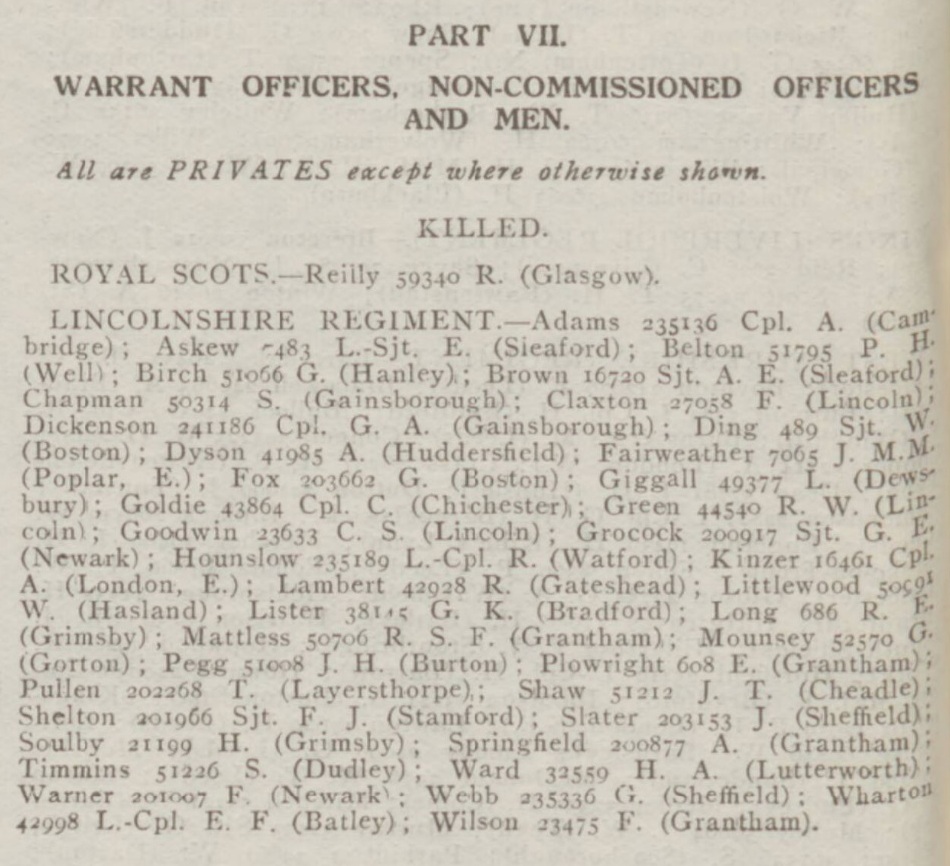

Bodies of dead killed on 24/10/18 were buried at GHISSIGNIES. It was found that the majority of the men had been deliberately shot in the head by the enemy. The men in question had been wounded: those that were able to walk were taken by the enemy and the remainder dealt with as stated above. Bodies of men of the Lincolnshire Regt. who had been killed about 30th Oct. were found to have been mutilated, hands hacked off at the wrists and eyes gorged [sic] out.

[13th Battalion Royal Fusiliers War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2538/3]

I have read plenty of British atrocities against German troops on the Somme in 1916 (there are files of such accounts in the archives at Freiburg). But on the British side I was only aware of Major Henry Hance’s (179 Tunnelling Company RE) description of Mash Valley on the Somme in mid-July 1916 in which he describes the British dead having been bayoneted ‘always thro’ the neck’ and the dead hanging on the wire having head their heads bashed in. But the 13th Royal Fusiliers war diary extract invited more research. Could this really have happened – British soldiers with hands hacked off and eyes gouged out by the enemy?

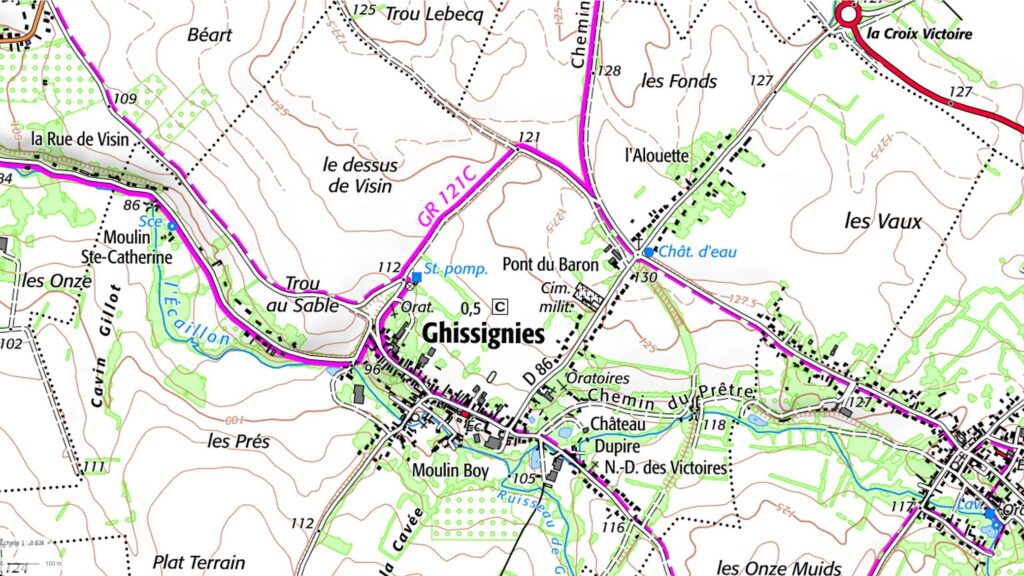

No additional information was available in the 13th Royal Fusiliers diary so moved on to the 8th Lincolnshire Regiment’s diary. The 13th Royal Fusiliers’ account had mentioned the battalion’s dead ‘who had been killed about 30th Oct.’ A brief look at the 8th Lincolns’ war diary confirmed any dead could not have been from that date (the battalion were in the line under heavy shellfire and had two Other Ranks wounded). Much more likely was the night of 2-3 November when ‘A’ Company raided German posts at the northern end of the village of Ghissignies, southwest of Le Quesnoy (of New Zealand Division fame).

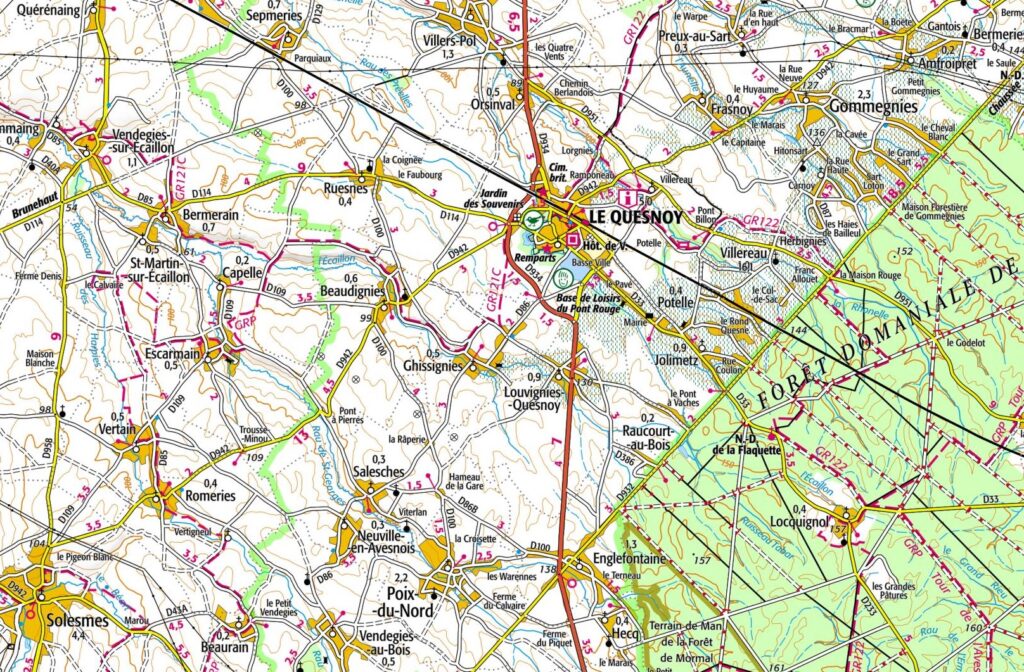

IGN map showing Ghissgnies in relation to Le Quesnoy

A Google Maps link to the village of Ghissignies can be found by clicking HERE.

The relatively sparse diary entries for 2-3 November are recorded below:

2/11/18 In the line – “A” Coy raided posts at level crossing in X5a at 23.45 hrs. Between 30 & 40 casualties inflicted on enemy. Heavy resistance offered. Casualties 11 O.R. killed, 18 O.R. wounded, 1 O.R. missing, 1 O.R. acc[identally] wounded.

3/11/18 In the line – Trench mortar activity on front line – casualties 12 O.R. killed, 17 O.R. wounded, 1 O.R. missing, 1 wounded acc. sprained wrist.

[8th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2529/1]

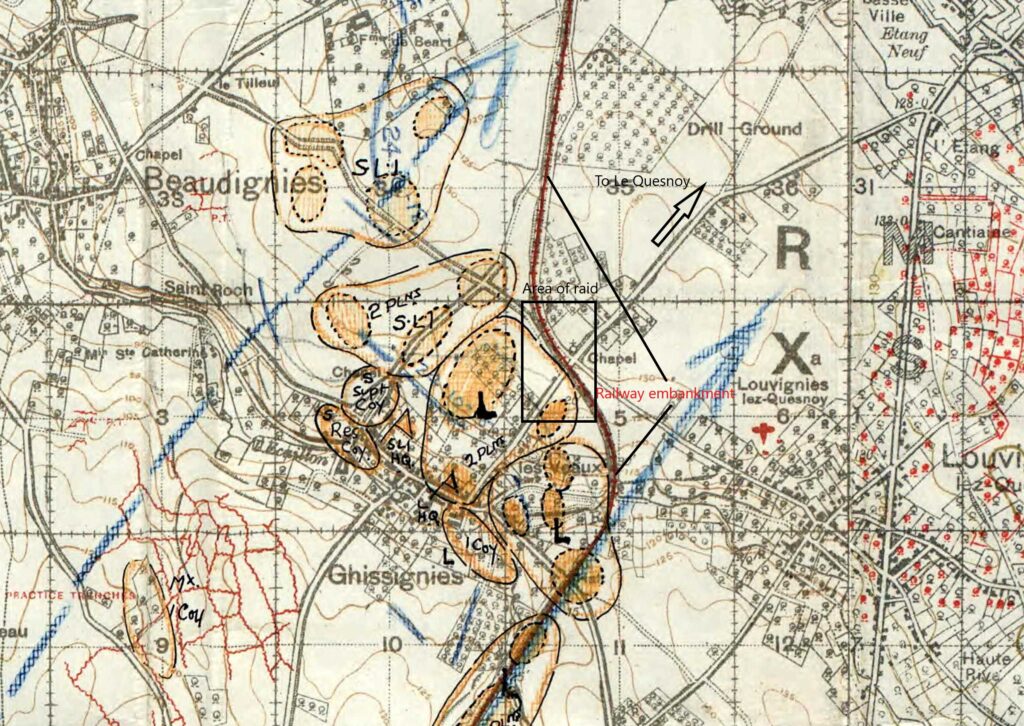

Annotated map extract from 37th Division HQ war diary showing Ghissignies and the chapel crossroads with area of raid marked

Clearly, the success of a single company raid which resulted in 31 casualties to the attacking force is questionable. The following day the Battalion cleared the position raided on 2 November with relatively little loss. Their casualties that day were the last sustained by the Battalion in the Great War.

4/11/18 “D” Company withdrew 2 platoons to SALECHES in X.19.b – 2 platoons followed left flank 111th Infantry Brigade mopping up the crossing & orchards in vicinity of chapel in X.5.a & b and R.35.. c & d. – 1 platoon establishing posts X.5.b.30.85 to R.35.d.15.15 –1 platoon X.b.20 – 70 to X.5.b.10.90. 24 prisoners captured in this operation – working from the south, 2 platoons of B. Coy mopped up Railway to Level Crossing in X.5.a.

In the evening the Bn moved to LOUVIGNY in area S.8.b & d.

[8th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2529/1]

As is so common when studying trench raids, the area in which this action took place is very small. British wartime maps (above) show the Le Quesnoy road leading to a crossroads at the north-eastern edge of the village. A chapel is marked on the crossroads but online research shows this to have been the existing calvary which was unveiled in 1852.

The Calvaire at the crossroads, Ghissignies. Image from: http://villesetvillagesdelavesnois.org/ghissignies/ghissignies.html

As part of 63rd Infantry Brigade, I hoped that the 8th Lincolns’ raid of 2-3 November would receive more attention in the Brigade war diary. And it was here that I struck gold with a detailed account provided in a Report on Operations, Oct 23rd – Nov, 4th, 1918, including gruesome descriptions of disfigurement and mutilation of British dead:

Nov 2nd.

At 2345 hours 8th Lincolnshire Regt. raided the enemy’s positions on the railway about the Chapel, X.5.a., under an artillery and trench mortar bombardment. This raid was carried out on a one platoon front with one platoon in close support. The railway was entered by the leading platoon and several casualties were inflicted on the enemy. 3 prisoners were taken but subsequently escaped. The supporting platoon was unable to reach the railway owing to heavy hostile machine-gun fire from the railway cutting. Our casualties were somewhat heavy, including 12 other ranks reported missing. In the subsequent advance on the 4th inst., the bodies of 11 were found buried by the enemy in the railway cutting. On being examined the bodies were found to have been terribly disfigured. One, the body of No. 241186 Corpl. G.A. DICKENSON, had six bayonet wounds, and one hand cut off. In addition both eyes were missing and had apparently been gouged out. It is not thought possible that these wounds could have been inflicted in the course of actual fighting.

[63rd Infantry Brigade War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2529]

A railway embankment bisected the Le Quesnoy road just before the crossroads. However, as noted in 63rd Brigade diary, British maps of the area were not wholly accurate:

The maps of this area had been found to be very misleading: what was taken to be a level crossing at X.5.a.5.5 was proved to be a very steep railway cutting fully 12 feet deep with a destroyed road bridge over the railway.

So, for the two assaulting platoons, what had appeared to be a standard raid had swiftly deteriorated into a tragic and bloody action. The war diary for 37th Division General Staff HQ reiterates the salient points of the raid:

Successful raid carried out by 63rd Brigade at 23.45 hours. Objective of raid level crossing X.5.a. Raiding party reached objective and inflicted severe casualties on the enemy. 3 prisoners were taken but owing to the escort being wounded on their way down with prisoners they escaped.

[37th Division Headquarters Branches and Services: General Staff War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2515]

However, it was 37th Division Intelligence Summary No 8., dated 7 November 1918 that provided most detail. It showed that the attacking force was met by sustained machine gun fire as soon as the advance began. One party working north along the railway made it into the 12ft deep railway cutting which was full of cubby holes, both at the bottom and higher up. Heavy fighting ensued and the report concluded thirty casualties were sustained by the Germans (almost certainly an overestimate – there are countless examples of British estimates of German casualties in raids bearing no relation to actual losses recorded in German reports. These numbers should always be treated with a healthy dose of scepticism – after all, those making the claim knew all too well there was no way their superiors could check inflated claims). Having suffered heavy casualties themselves and low on bombs and ammunition, the party withdrew. Other parties aiming to work south along the railway were stymied by sustained machine gun fire which caused heavy losses amongst the attacking Lincolns.

There is also mention of three German prisoners shooting their lone escort and escaping and a warning that prisoners should be properly searched for weapons upon capture to prevent such instances occurring.

7/11/18.

A raid was carried out on the night 2/3rd of November by two platoons of the right Bn in the vicinity of the level crossing in X.5.a. at 23.45 hours. The assembly was successful, but two machine guns, one on the railway crossing and the other about 30 yards north of the house X.5.a.40.35 opened fire immediately the party started to advance. One party, working north along the railway reached the hedge in spite of heavy fire, crossed it, and dropped into the railway cutting which was found to be full of cubby holes, both at the bottom and higher up.

The party started to mop up at once but was unable to reach the machine-gun at the level crossing. 30 casualties were inflicted on the enemy in spite of considerable opposition, particularly from the men in the upper cubby holes.

The party was finally forced to withdraw, their bombs and ammunition being exhausted and only one officer and 2 O.R. remaining unwounded.

Three prisoners was sent back under a lightly wounded escort. One of those prisoners drew a revolver and shot his escort. The escort of the other two was again wounded whilst withdrawing and they also escaped.

Other parties attempting to mop up posts in X.5.a.5.4 and to work south along the railway were unable to gain ground owing to heavy machine-gun fire in spite of repeated efforts to knock out the guns. The majority of our men were wounded in this attempt.

The raid was successful in that it showed that the enemy was still holding this section of the front in strength.

NOTE. The loss of the three prisoners emphasises the fact that prisoners should be thoroughly searched for weapons directly they are captured.

[37th Division Headquarters Branches and Services: General Staff War Diary, UK National Archives, Ref: WO95/2515]

Based upon these accounts it seems most likely the soldiers recorded in 63rd Brigade war diary whose ‘bodies were found to have been terribly disfigured’ probably came from the party which entered the railway embankment and fought so bitterly with the enemy ensconced in their cubby holes. Sadly, I doubt it will be possible to find further information on the events of that night – whether or not the wounds to British soldiers were deliberate but experience leads me to believe they were. The troops had seen their fair share of fighting and killing and knew the difference between wounds sustained in the course of action and deliberate mutilation. That these accounts are taken from official British sources (war diaries from Battalion, Brigade and Division) as opposed to a post-war memoir also adds credence to their veracity. Furthermore, by this stage of the war there was no need for inflated accounts of German atrocities to be used for propaganda.

It is certainly possible that assaulting Lincolns who entered into a bloody fight in the railway embankment, killing a number of German defenders were offered no mercy. Maybe German survivors were not in the mood to take prisoners and wanted revenge? To assume such incidents did not happen over four years of a bitter war is naïve and misses the essential point of warfare – namely, to kill the enemy.

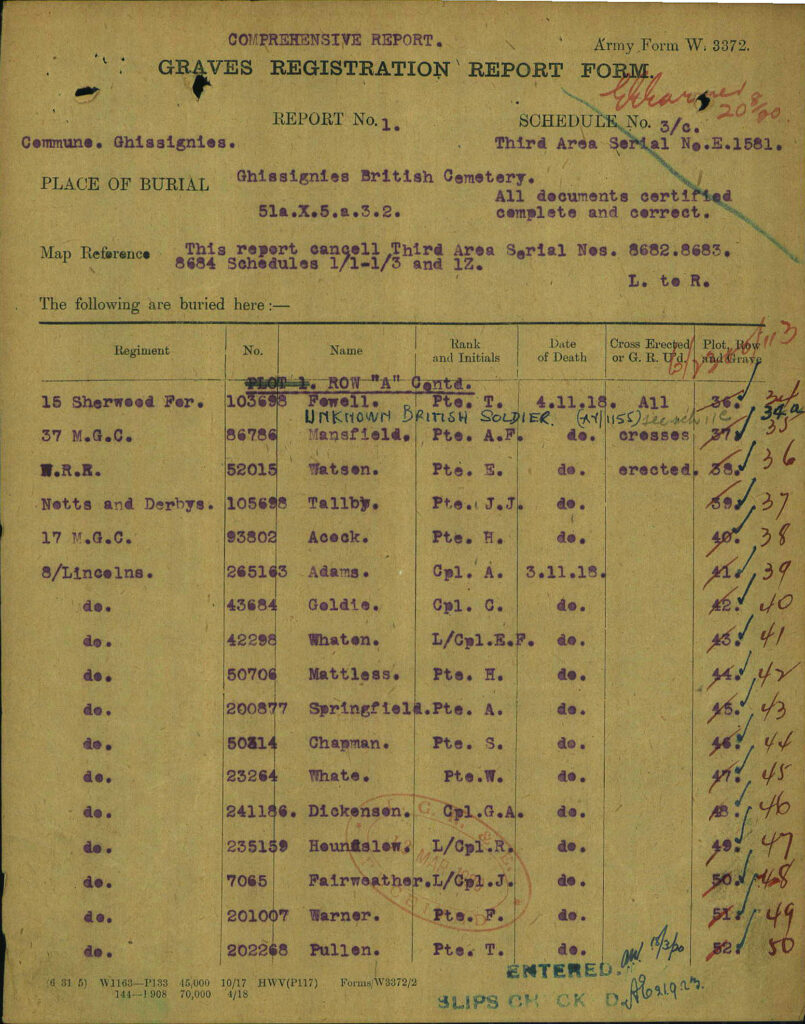

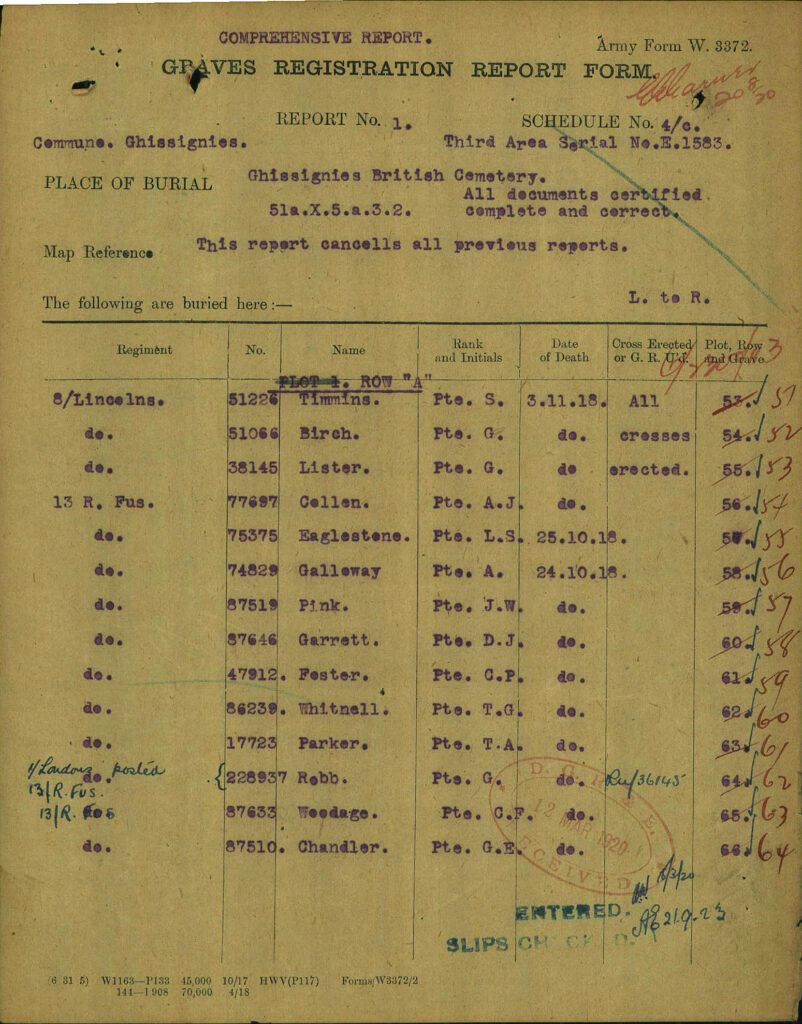

As for the 8th Lincolns dead, there are sixteen soldiers from the Battalion now buried in a long line in the nearby Ghissignies British Cemetery. Based upon the sources above, eleven of these were disinterred from their shallow burial in the railway embankment – these are the men whose bodies were disfigured – with the remaining five ‘conventional’ casualties from the action (most likely from machine gun fire as they attempted to work south along the railway).

Below is a list of these dead taken from the CWGC website.

It includes 241186 Corporal George Dickenson whose body had six bayonet wounds, one hand cut off and both eyes missing (apparently gouged out). Two graves along lies 7065 Lance Corporal John Fairweather MM, a recipient of the 1914 Star who went overseas with the 1st Battalion in September 1914, served with a number of different battalions and earned the Military Medal in 1917. I would welcome any further detail on these men. Many of the dead from this raid are listed in the Weekly Casualty List (War Office & Air Ministry ) for 28 January 1919.

Weekly Casualty List (War Office & Air Ministry ) – Tuesday 28 January 1919

So, a strange and disturbing case of battlefield mutilation right at the end of the war. The village is once more a quiet spot and a roundabout now sits at the road junction. A water tower has been built between the Route de le Quesnoy and Route de Louvigny. Other than the military cemetery 100 metres down the road towards the village centre there is nothing to indicate any fighting took place here. When we get out of lockdown and visits to France and Flanders recommence I will stop at Ghissignies, far from the well-trodden spots of the Ypres Salient or the 1916 Somme battlefield and pay my respects to those men killed just a few days before the guns fell silent.

Modern aerial view of raid site at Ghissignies. Taken from Geoportail

IGN map of the village of Ghissignies

Image from Google Street View looking up to site of railway embankment and raid

13 Sept 1949 aerial of Ghissignies, the railway embankment and crossroads

15 November 1968 aerial of Ghissignies showing water tower to the east of the crossroads

JB, 31 March 2021

Following in the footsteps of Godfrey Hinnels with Hugh Dennis for ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’

Last January I spent three days filming with Hugh Dennis for Wall to Wall’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ series. We were following in the footsteps of Hugh’s maternal grandfather, Godfrey Parker Hinnels. Godfrey served with the 1/4th Battalion Suffolk Regiment from Spring 1917 until his transfer to the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment in March 1918. Despite having just over a year on active service Godfrey certainly saw his share of action, going ‘over the top’ at Arras and Ypres as well as fighting during the German Kaiserschlacht and the defence of Wytschaete in April 1918. This article is designed to provide more information on those units and their actions covered in tonight’s episode.

Last January I spent three days filming with Hugh Dennis for Wall to Wall’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ series. We were following in the footsteps of Hugh’s maternal grandfather, Godfrey Parker Hinnels. Godfrey served with the 1/4th Battalion Suffolk Regiment from Spring 1917 until his transfer to the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment in March 1918. Despite having just over a year on active service Godfrey certainly saw his share of action, going ‘over the top’ at Arras and Ypres as well as fighting during the German Kaiserschlacht and the defence of Wytschaete in April 1918. This article is designed to provide more information on those units and their actions covered in tonight’s episode.

Battle of Arras

Godfrey’s Suffolk battalion formed part of 98th Brigade, 33rd Division. It did not participate in the initial advance on the morning of 9 April 1917 but was moved up close to the front line on 12 April, occupying a position on the road between Henin-sur-Cojeul and Neuville Vitasse, the scene of bitter fighting on the battle’s opening day. The battalion war diary records ‘A great deal of burial and salvage work was done by the battalion in the vicinity of the trenches in front of the Hindenburg line’. Godfrey’s initiation into active service can hardly have been harsher; searching through the blanket of snow carpeting the battlefield for men killed a few days earlier. There followed a move into the Hindenburg Line itself for a spell in the trenches before the battalion’s major effort in the Arras offensive.

Hugh Dennis and I go through the Suffolks attack at the sunken lane in the Sensée valley. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

At 4.45am on 23 April 1917 a huge British artillery onslaught fell on to the German trenches signalling the start of the Second Battle of the Scarpe. Godfrey’s battalion was tasked with bombing their way down 2,300 yards of both front and support trenches of the Hindenburg Line to the Sensée River. Despite the support of tanks and artillery this was still a highly ambitious task, being prosecuted down a strong system of trenches, specially designed for defence. A deep tunnel ran under the support trench offering accommodation, headquarters and stores. The initial advance was spectacular with the Suffolks reaching a sunken road between Croisilles and Fontaine-les-Croisilles within two hours. Just 200 yards short of their objective they then came under sustained German fire. Later that day a strong German counter-attack pushed them back in both trenches – they ended the day close to the morning’s starting position. Despite taking a remarkable 650 German prisoners in the initial advance the battalion suffered over 300 casualties (about 50% of the battalion strength). This bloody day’s fighting is chronicled in great detail in ‘From the Somme to the Armistice’, the memoirs of Captain Stormont Gibbs MC, an officer in the 1/4th Suffolks.

The village of Fontaine-les-Croisilles bathed in evening sunshine. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

Passchendaele

Following their mauling in the Hindenburg Line the battalion’s losses were made up with reinforcements. Back to fighting strength they moved north to the coast before heading to Ypres to take part in the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). The battle had commenced on 31 July but unexpectedly heavy rainfall in August coupled with the destruction of the delicate Flemish drainage system by millions of artillery shells had reduced the landscape to a shattered Stygian moonscape of overlapping shell holes. Any advance had been limited but September’s improvement in the weather gave the battlefield time to dry out. Ironically, considering the common perceptions of Passchendaele, dust became a problem with roads and tracks watered regularly to restrict dust clouds caused by passing troops and transport.

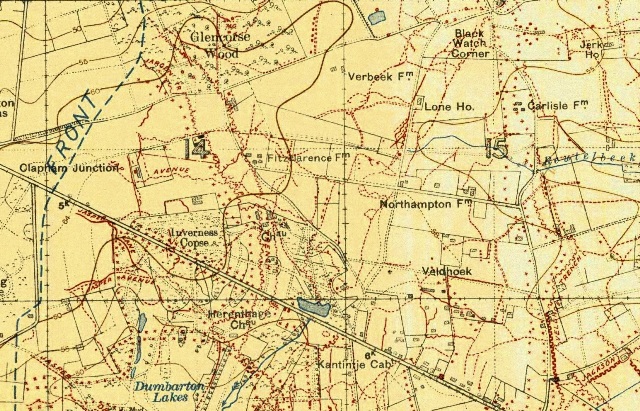

It was into this landscape that the Suffolks found themselves in September 1917. By 11.30pm on 25 September they were holding a line of trenches on the infamous Gheluvelt Plateau running between Fitzclarence Farm and Glencorse Wood, close to Polygon Wood. The plan was for the battalion to leave their positions, advance towards Black Watch Corner where a line of shell holes marked the British front line and join in the general attack at Zero Hour, 5.50am on the 26th.

The Suffolks were shelled prior to Zero Hour and heavy casualties sustained. The Battalion War Diary makes for depressing reading: ‘The heavy shelling, thick mist and darkness caused confusion and it was impossible for the men to keep touch but Platoon rushes were made and some Platoons made progress.’ Any great advance was impossible and by day’s end the battalion had only managed to advance to a line near Black Watch Corner. The battalion had achieved little and lost around 250 men in the process.

Extract from British trench map dated 14 September 1917 showing the Suffolks' battlefield - Fitzclarence Farm, Glencorse Wood and Black Watch Corner can be clearly seen.

The Passchendaele section was not broadcast but has been included as ‘unseen footage’ on the ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ magazine’s website here: http://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/footage/13822.

Winter 1917/1918 & Talbot House

The battalion took no further part in offensive action but spent the next six months in and out of the line on the Passchendaele ridge. When not in trenches the Suffolks were at rest in camps close to the small town of Poperinghe. Whilst not documented, it is highly likely Godfrey would have visited Talbot House – the “Every Man’s Club” situated in the bustling town’s heart. At our first meeting I had described Talbot House (also known as Toc H) to Mark Bates, the director of Hugh’s episode, and suggested a visit. It would be a good buy alprazolam .5 mg opportunity to show a typical soldier’s experiences when out of the line. We visited during our recce in December 2011 and, like so many before, I could tell Mark was taken with Talbot House. The house has a unique atmosphere rarely encountered in other buildings and I was delighted to see the Talbot House section so prominent in the final edit.

Spring 1918

On 1 March 1918 Godfrey headed south to the Somme where he joined the 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, part of the 21st Division, holding trenches near the village of Épehy, once again opposite the Hindenburg Line. The exact reason behind his transfer is not documented but coincides with the 1/4th Suffolks becoming a pioneer battalion. It may have been that Godfrey’s skills were required more in a frontline infantry battalion as opposed to a pioneer battalion. He was soon into action as the Germans launched their Spring Offensive (Kaiserschlacht) on 21 March. Deluged with gas shells the Lincolns were attacked under cover of ‘a heavy white mist’. A day of desperate fighting followed with positions held around Chapel Hill before relief and retirement across the 1916 Somme battlefield. On 1 April the Lincolns entrained north to Flanders but hopes for a rest were short lived.

On 9 April a German attack south of Armentières heralded the start of the Battle of the Lys. A huge hole was punched in the Allied line and with his southern flank crumbling General Plumer, commanding the Second Army, ordered a withdrawal from the Passchendaele Ridge back to positions close to Ypres and the Yser Canal. The situation was desperate.

Wytschaete (now renamed Wijtschate) under a heavy sky. This view is looking north-east towards Staenyzer Cabaret crossroads. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

On the evening of 12 April with the battalion at less than half strength the 1st Lincolns were sent to defend the village of Wytschaete (nicknamed Whitesheet by British soldiers), holding a line between Staenyzer Cabaret crossroads and Bogaert Farm. Messines, directly to the south, had fallen two days previously and with Wytschaete the next village along the ridge an attack was almost inevitable. At 4.30 am on the morning of 16 April a heavy artillery bombardment pounded the British front line, the village and all approaches, lasting for 70 minutes. The official account of the operation details the subsequent events:

“Under cover of a dense fog the enemy attacked on the flanks of the battalion, and succeeded in breaking our line just North of the STANYZER CABARET Cross Roads, and at PECKHAM. Strong parties of the enemy then wheeled inwards and attacked both flanks of the battalion…Owing to the dense fog and bombardment it was impossible to get a clear idea of the situation and the Companies did not know they were attacked until the enemy appeared at close quarters. Fighting under every disadvantage, as the fog denied them the full use of Lewis Guns and rifles and made it impossible to locate the enemy, the battalion stood firm, and fought it out to the last. No officer, platoon post or individual surrendered and the fighting was prolonged until 6.30 am. Ample evidence of this is provided by the Commanding officer [Major Gush MC] and Battalion H.Q. who made a last stand at the Cross Roads, and did not leave there until 7 am. They, a mere handful of men, withdrew slowly, fighting all the way through WYTSCHAETE WOOD.” [National Archives Ref: WO95/2154]

The Lincolns had provided a magnificent display of defensive fighting in tremendously difficult conditions. During the action Godfrey was wounded in his index finger – a wound that prevented his return to frontline service. The following day a mere 5 officers and 82 other ranks were relieved to be joined by a further 21 stragglers who had become attached to other units during the fighting. Having gone into action with over 400 men, the Lincolns’ stubborn defence had been bought at a high price – the casualty rate was nearly 75%. The losses were not in vain as Brigadier General Cater commanding Godfrey’s Brigade noted how the ‘hard fighting left the enemy disorganised and unable to consolidate; and materially assisted the counter-attack delivered in the evening.’

At Wytschaete reading the account of the 1st Lincolns stand on 16 April 1918. Image copyright Paul Nathan & is reproduced with his permission.

Matching soldier’s reminiscences to actual actions can often be problematic but by studying Godfrey’s war service it soon became clear his story of fighting Germans on a hilltop must have related to the defence of Wytschaete. It was a remarkably satisfying conclusion to stand with Hugh Dennis on the same ground where his grandfather fought so gallantly ninety four years earlier.

My thanks to Paul Nathan for his agreement to use his photographs from filming, Mark Bates, Mike Robinson and all at Wall to Wall for their help plus Peter Barton for various maps & documents.

If you would like to read more about these battles and places then a very short suggested reading list is included below:

- Peter Barton with Jeremy Banning, Arras – The Spring 1917 Offensive in Panoramas including Vimy Ridge and Bullecourt (Constable, 2010)

- Jonathan Nicholls, Cheerful Sacrifice: The Battle of Arras 1917 (Leo Cooper, 2005)

- Peter Barton, Passchendaele – Unseen Panoramas of the Third Battle of Ypres (Constable, 2007)

- Paul Chapman, A Haven from Hell – Talbot House, Poperinghe (Cameos of the Western Front) (Pen & Sword, 2000)

- Chris Baker, The Battle for Flanders: German Defeat on the Lys 1918 (Pen & Sword, 2011)